Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

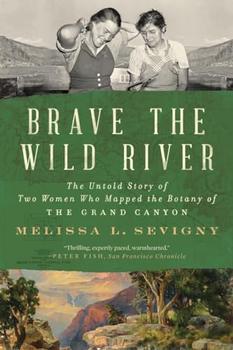

The Untold Story of Two Women Who Mapped the Botany of the Grand Canyon

by Melissa L. Sevigny

But just four days into the trip, things had already gone badly wrong.

Earlier that day, the crew had pulled the boats ashore at the confluence of the Green and Colorado rivers. The trip's leader, Norman Nevills, wanted to scout the rapids ahead and plot a careful route through them. The river was high with snowmelt, chewing up whole trees and spitting them out like toothpicks. Then a boat pulled free from its mooring and spun into the current. Jotter heard a shout and dashed to the shore to see the boat sail by, captainless and undirected. Recklessly she followed her oarsman, Don Harris, into a second boat to give chase. Harris rowed while Jotter bailed water with an empty coffee can, hands cut and bleeding from its jagged rim. Battered and breathless, the two swept four miles downstream before finding the lost boat aground. Harris left Jotter there and walked upriver to rejoin the rest of the crew, promising to return. Night fell. Nobody came.

Jotter had plenty of time, as she gathered a fresh armload of driftwood and stirred the coals back to flame, to recall what everyone had told her about running the Colorado River. The few people who had ventured this far told stories of wreckage flung along the rocks, and skeletons tucked into stony alcoves with withered cactus pads clutched in their bony fingers. She had passed, on the journey down the Green, the names of other river runners painted in white on the canyon walls: names made familiar by newspaper obituaries. Locals bragged, with a kind of gruesome glory, that the Colorado was the most dangerous river in the world.

It was not dangerous because of its size or steepness. Its volume was unimpressive: a whole year's worth of water flowing down the Colorado was what the Mississippi delivered to its delta in two normal weeks. The Colorado averaged a drop of nine feet a mile over its 1,450-mile length, and stretches of the river were nearly flat. It ought to have been the most ordinary river in the United States. But the Colorado was an unruly thing, governed by the mad rhythms of a desert climate. Surges of snowmelt, thick with mud, came down each spring, followed by torrents of storm water in summer. Every flood carried a fresh barrage of boulders and debris torn from the land and tossed in the river's maw. This was what made the Colorado so difficult to run: landslides and slurries at the mouth of every tributary, churning the river to a frothy roil with whirlpools, stomach-somersaulting drops, and standing waves big enough to swallow a boat whole.

To make matters worse for travelers, the strength of those floodwaters and the abrading power of the silt had turned the river into a knife. It had sliced the Colorado Plateau into a marvelous maze of canyons in Utah and Arizona. The steep walls added another element of danger. Should something go wrong—if the boats were smashed to smithereens—there would be no help forthcoming, and little chance of escaping by foot up the cliffs and over the desert.

Cataract Canyon, where Jotter was stranded, was only the beginning: their first test, and they had failed. The Grand Canyon still lay ahead. By 1938 only a dozen expeditions—just over fifty men, all told—had successfully traversed the Grand Canyon by boat since John Wesley Powell's journey nearly seventy years before. Only one woman on record had attempted the trip: Bessie Hyde, who vanished with her husband, Glen, on their honeymoon in 1928. Their boat was left empty; their bodies were never found. People said women couldn't run the Colorado River. Well, Clover and Jotter weren't just women: they were botanists, and they were going to try.

Jotter had time to remember those stories and to wonder what had happened to her companions—somewhere upriver, no doubt trying to reach her. But the night stretched on and they didn't come. An unseen fish splashed out on the water. The fire burned to embers. Two rowboats, their fresh white paint showing new scores and scrapes, listed on their sides on the riverbank. Jotter checked the ropes that anchored them, and nervously, checked again. She dragged out the bedding and spread it to dry in the firelight. She unpacked the drenched bags of food, matches, and cigarettes. She stoked the fire with another stick of driftwood, gleaming and polished from its tumble downriver. She put her back to a stone and her face to the flames. She toasted some bread and ate it. The river was rising, and soon she had to move the fire back from the encroaching edge. Stars bloomed in the sky overhead, one great river of stars, a perfect echo of the real river below.

Excerpted from Brave the Wild River by Melissa L. Sevigny. Copyright © 2023 by Melissa L. Sevigny. Excerpted by permission of W.W. Norton & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

I always find it more difficult to say the things I mean than the things I don't.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.