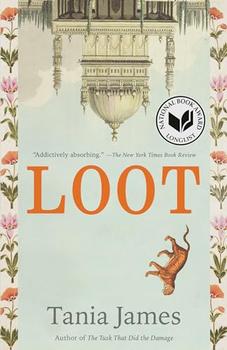

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

by Tania James

At the moment, Abbas has no interest in leaving a mark. All he wants is to stay out of trouble, though it is, perhaps, a little late for that.

Abbas has never been to the Summer Palace before, but he has made eight toys for Zubaida Begum, one of the high-ranking consorts of Tipu's zenana. The carved animals moved by hand crank: elephants, tigers, and horses. Soon after Abbas made one for Zubaida Begum, she ordered seven more, one after another.

To collect the toys, she sent a man by the name of Khwaja Irfan. From a distance, Abbas would watch Khwaja Irfan coming down the lane, easy to spot in his brassy cloaks of green or marigold, silks that spoke of royal places. He had a pointy chin and keen eyes, no facial hair to disguise the fineness of his features. "What's the matter?" he asked Abbas the first time they met. "Never met a eunuch before?"

Abbas shook his head.

"Then I'm your first. How fun for me." Khwaja Irfan closed the umbrella he'd been using to shield himself from the sun.

Abbas was taken with the umbrella's handle, how it curved up into the graven head of a tiger.

Khwaja Irfan noticed him staring. "Nice, isn't it. Pure elephant ivory."

Abbas eyed the cut of the teeth and said: "No." "What do you mean, no?"

"Ivory wood, maybe. Whoever told you otherwise was lying." Khwaja Irfan appraised him with a sly smile. "Okay, Know-It-

All."

Somehow Khwaja Irfan would manage to tuck that phrase into each of his visits, a teasing that made him feel like family. Or at least like the sort of family Abbas would've requested had he any choice in the matter. His brothers were chipped from the same block of stone as their mother—blunt, judgmental, suspicious of smiley types. Of eunuchs his mother said that they were gossips and could never be trusted.

The family regarded Abbas's toys with a similar mix of disdain and skepticism. Only his father took a sheepish interest, asking for the occasional demonstration, which often ended with him saying, "How do you come up with these things?" This, to Abbas, was the highest of praise.

It made Abbas doubly proud to deliver the begum's payment to his father. The rupiya always came in a silk drawstring pouch, embroidered in gold with Tipu's tiger insignia. Before handing the pouch to his father, Abbas took a private moment to hold it to his nose and inhale.

Rosewater. Betel. Mysterious womanly smells.

"The real thing smells better," came a remark from Farooq, tailed by laughter.

Abbas shuffles ahead of the guard, down a row of artisans ordered by the nobility of their crafts: the potters, the weavers and embroiderers, the goldsmiths and blacksmiths, the muralists and miniaturists. ("At least we're not next to the leatherworkers," their father used to say about being at the far end. "We're quite a ways from them.") There is Ustad Mahfuz and deaf Bilal, Madhava the Younger and Madhava the Disciple, Tariq and Khandan and old Ustad Saadat with his weird glass eye, tossing a bit of bread to a stringy dog.

Some of them stare. Others know better.

Though the forges are behind him now, Abbas can still hear a hammer clinking against iron, can still picture that white-orange rod wilting as if by magic, the air above it shimmering. Abbas has always liked watching the blacksmiths. It occurs to him now that he may never watch them again.

A pair of peepal trees wave him along, their leaves softly gossiping in his wake.

Soon he comes to the Water Gate, the tunnel that allows commoners to enter and leave the city. The same gate through which Yusuf Muhammad led them twelve years ago, along with a number of other woodworkers from Shimoga, all of them recruited by Tipu's father to carve the walls and columns of the Summer Palace. Yusuf Muhammad took a look around at the capital city—at the whimsical footbridges and gold-leafed fountains, at the mighty temple gopuras and the soaring minarets, not a poor person in sight, even the stray dogs lounging about with an air of satisfaction—and thought: Why leave? What reason would one have to abandon the protective walls of Srirangapatna?

Excerpted from Loot by Tania James. Copyright © 2023 by Tania James. Excerpted by permission of Knopf. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.