Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Uyghur Poet's Memoir of China's Genocide

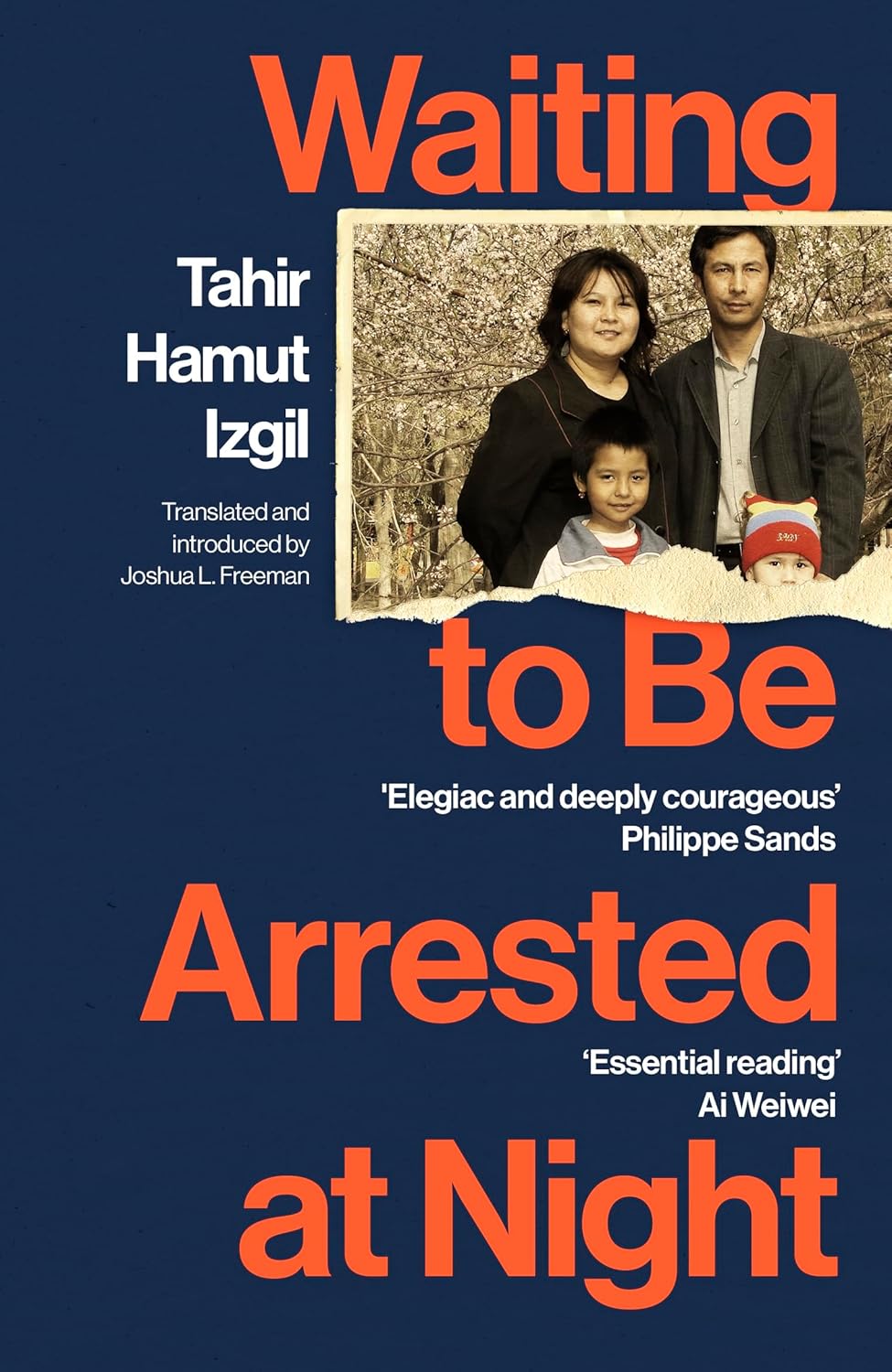

by Tahir Hamut Izgil

Despite all this, Ilham never believed that the government would formally arrest or imprison him. He was, after all, a professor at a university in the national capital, and considered his vocal criticism to be entirely within the law. The fact that his household was registered in Beijing also lent him some peace of mind. But the political climate in the capital was very different from that in the Uyghur region. If Ilham had engaged in the same activities in Xinjiang, he would already have been arrested.

Things did not turn out as Ilham thought they would. In mid-January 2014, news of Ilham's arrest at his Beijing apartment reached us in Urumchi. When I heard the news, I inquired as to which police force had arrested him, and was told that the officers had arrived from Urumchi.

It was not normal for Urumchi police officers to travel more than two thousand kilometers to arrest a professor at a university in Beijing. Normally, if Ilham were to be arrested, the Beijing police would have jurisdiction. The involvement of the Urumchi police meant that Ilham's arrest was a decision made at the highest levels. Not long after, we learned that a number of Ilham's Uyghur students had disappeared from their school around the same time, likely into police custody. In other words, the situation was grave.

I was alarmed by the arrest of an intellectual who had merely called for the government to enforce its own laws. It gave me the sinking feeling that catastrophe lay ahead for Uyghur intellectuals as a group. As a measure against the approaching danger, I set aside time to review the files in my laptop as well as my desktop computer at work, and deleted every document, video, recording, and image that police could conceivably seize on as a pretext. I directed every employee in our office to conduct a similar "cleaning" of their own computer.

Not long before, while browsing the internet, I had come across "Charter 08," a manifesto in which the Nobel Prize-winning Han dissident Liu Xiaobo and others called for democracy and civil liberties in China. After reading the manifesto, I decided to translate it into Uyghur; but, as I had no chance to publish the translation, it just sat on my computer. A couple of years earlier, a friend had given me a Word file with a Chinese translation of Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland, a collection of scholarly articles by more than a dozen specialists from the United States and elsewhere. The People's Liberation Army's political department had translated the book into Chinese, presumably for internal circulation. Given the tight state control over information from abroad, I was eager to get my hands on any foreign materials I could relating to Uyghurs and our homeland, and I read the book cover to cover at least three times. I also had a PDF of Han writer Wang Lixiong's book My Western Regions, Your East Turkestan, which had been published in Taiwan. And there was a photo that the Dalai Lama had taken with exiled Uyghur leader Rebiya Kadeer, his arm draped affectionately around her shoulder. I had been moved to see this warm connection between leaders of two communities facing oppression in China.

It had taken me a great deal of effort to find and translate these materials, and my unease grew as I reluctantly deleted them one by one. Later events, though, would prove this decision correct. Things were getting worse.

The repression following the 2009 violence in Urumchi had not yet concluded when the government began a separate campaign directed at Uyghurs. Known as "Strike Hard," this campaign was supposed to target "religious extremism, ethnic separatism, and violent terrorism," and its effects were far-reaching. Han migrants began arriving in Xinjiang in even greater numbers than before; Uyghurs' homes were demolished and their land confiscated. Uyghur religious practice and cultural life were increasingly suppressed, and Uyghurs faced ever-increasing discrimination in daily life. The problems Ilham Tohti had identified did not merely go unaddressed; they festered. Yet the government insisted that any Uyghur discontent stemmed from separatism and terrorism, and punished people indiscriminately.

From Waiting to Be Arrested at Night: A Uyghur Poet's Memoir of China's Genocide by Tahir Hamut Izgil by Tahir Hamut Izgil, translated by Joshua L. Freeman. Copyright © Tahir Hamut Izgil, 2023. Published by arrangement with Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Random House LLC.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.