Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

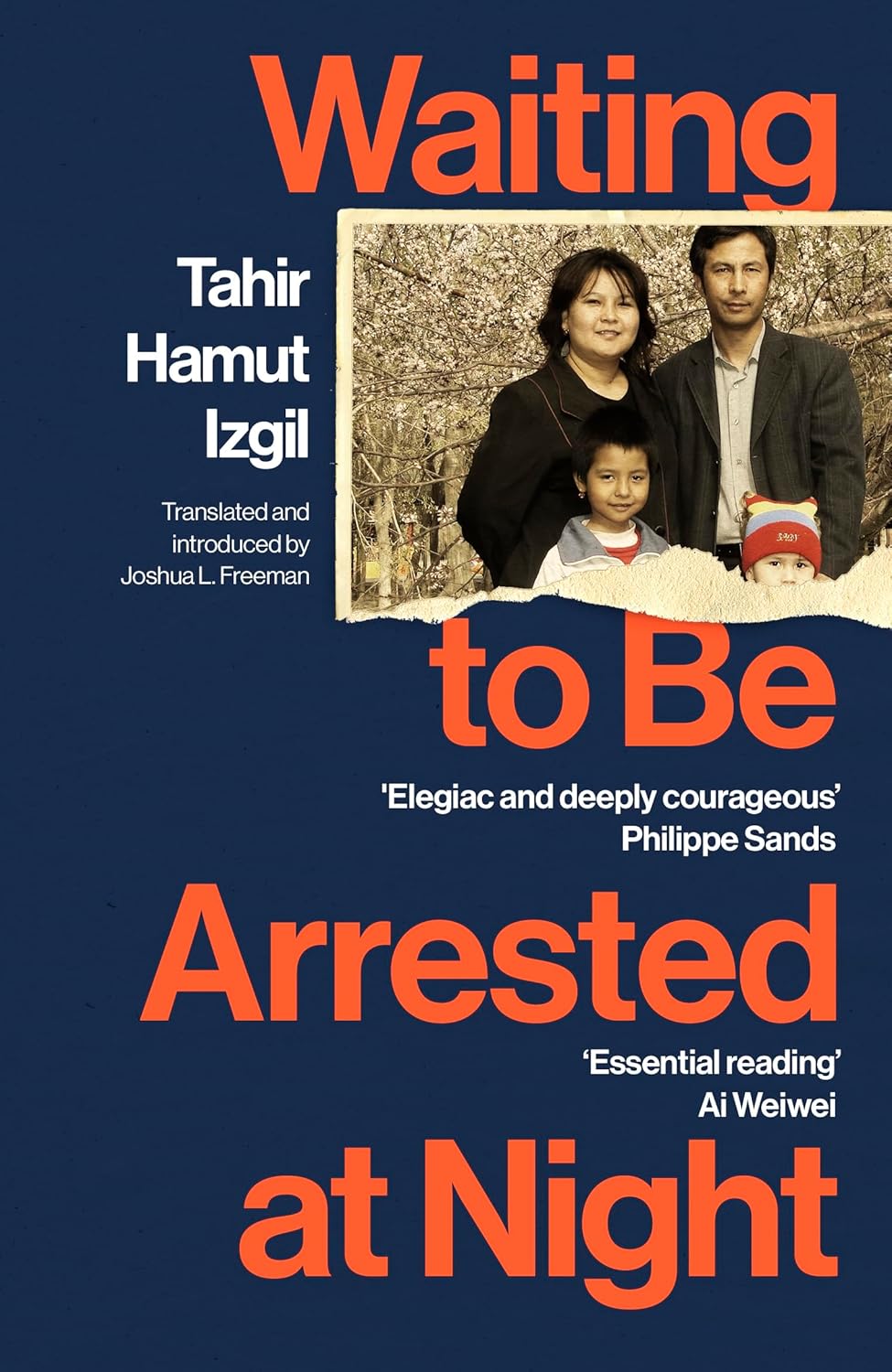

A Uyghur Poet's Memoir of China's Genocide

by Tahir Hamut Izgil

Two months after Ilham Tohti's arrest, in March 2014, news came of a terrorist incident at a railway station in the southern Chinese city of Kunming, thousands of kilometers from Urumchi. State media announced that five black-masked Uyghurs had attacked people with knives in the ticket-sales hall.

Another two months passed. State media reported that two Uyghurs armed with knives had attacked passengers at the exit to the Urumchi train station before blowing themselves up. Not long after, it was reported that Uyghur terrorists had carried out a suicide attack on a morning market in Urumchi.

In the years immediately following the 2009 violence in Urumchi, the situation in the Uyghur region had seemed calmer. Now, with this spate of violent attacks in the space of three months, things once again grew tense. The government's posture and rhetoric became more aggressive than ever.

Uyghurs typically referred to such incidents by saying "Something's happened." People I knew had complex feelings about these events. On the one hand, their resentment toward the government and the Han made them feel on some level that it served them right. On the other hand, they felt it was wrong to target civilians rather than the government. In addition, people worried that such incidents would result in even more state repression that could personally harm them. Those negatively affected would grumble, "Instead of doing these stupid things, why can't these people just be grateful for their daily bread?"

State media reports on such events were generally vague, contradictory, and unpersuasive. Suspicions, guesses, and rumors spread rapidly. Government propaganda insisted that all such violent events were carried out by separatists and terrorists who aimed to split Xinjiang from China and establish an independent East Turkestan. The government refused to acknowledge any potential causes for the violence in its own policies and in Uyghurs' own lives.

Among Uyghurs, though, all manner of accounts circulated about the origins of these attacks. For the most part, these accounts portrayed the authors of the attacks as having been victims of state injustice, bent on revenge. There were even those who believed that the government itself planned and carried out the violent incidents to provide a pretext for further repression, and to break Uyghurs' will to resist.

In addition to punishing the individuals involved in each violent incident, it was the government's practice to harshly punish people who had nothing to do with the incident but who were in some way related to the perpetrators: their relatives and acquaintances, people who had once shared a meal with them, people who had once had them over as houseguests. Such people were accused of having "taken terrorists under their wing."

Like many other Uyghur intellectuals, I was quite interested to know how these incidents were reported in foreign media and what sort of reaction they elicited abroad. Following the 2009 violence in Urumchi, the internet was shut down in the Uyghur region for nearly a year. Even after it reopened, numerous foreign websites-especially news websites-were blocked; accessing them was considered a serious crime. Despite this, we furtively used VPNs to circumvent the state's notorious Great Firewall and peruse various international news websites. We had so little access to information about our own homeland and what was happening around us that we were willing to take that risk.

Now, as state surveillance and control grew still tighter following Ilham Tohti's arrest and the string of violent incidents, there remained little choice but to delete our VPNs and forgo international websites entirely. Without the opportunity to use the global internet, it seemed that listening to foreign news with a shortwave radio might be my only option.

That summer vacation, our family went to Kashgar. We visited my parents and spent time with old friends. The husband of one of Marhaba's college classmates sold electric appliances at a shopping mall in Kashgar. I decided to buy a shortwave radio from him; I figured he could recommend a good one.

From Waiting to Be Arrested at Night: A Uyghur Poet's Memoir of China's Genocide by Tahir Hamut Izgil by Tahir Hamut Izgil, translated by Joshua L. Freeman. Copyright © Tahir Hamut Izgil, 2023. Published by arrangement with Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Random House LLC.

Common sense is genius dressed in its working clothes.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.