Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

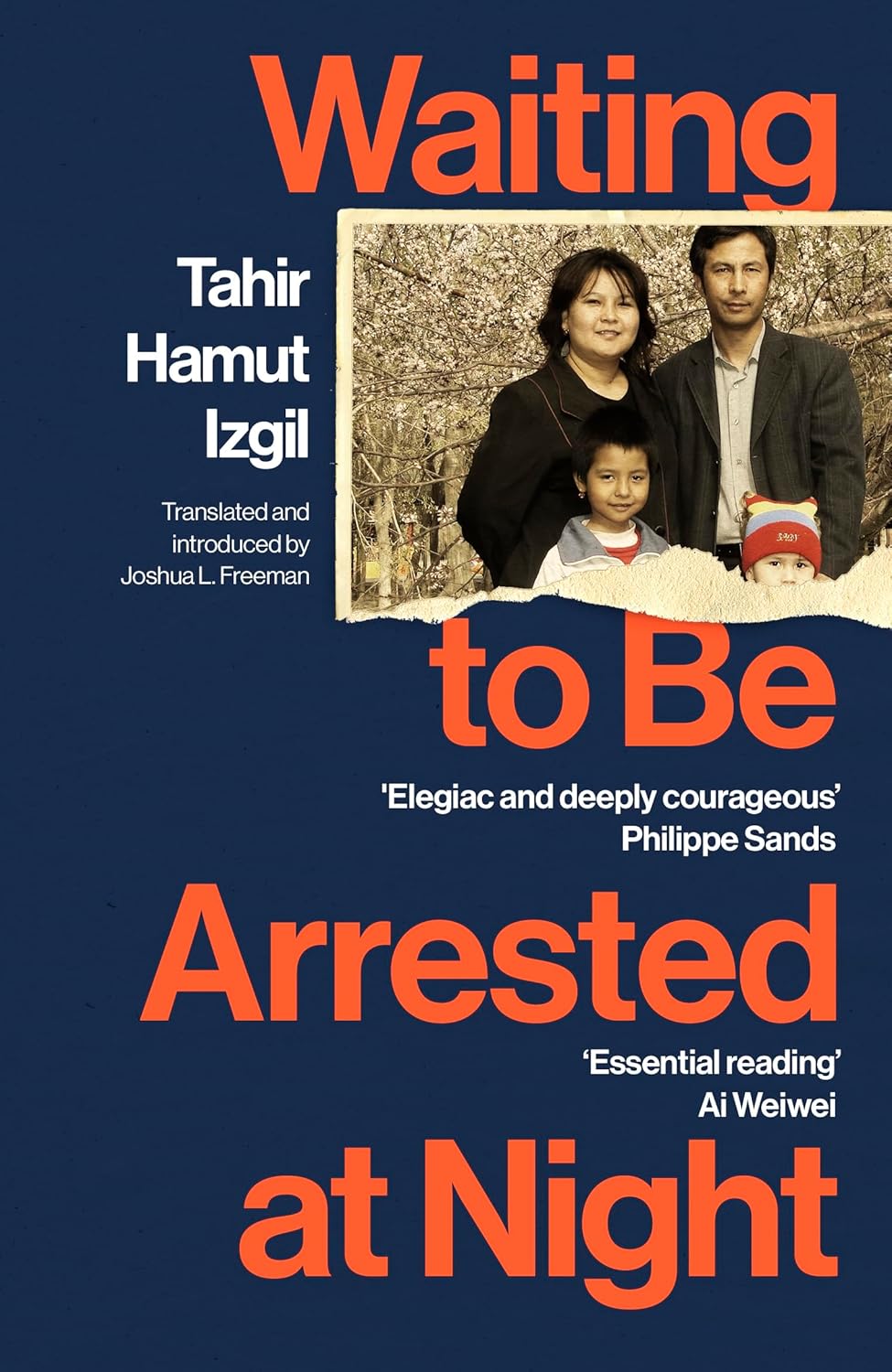

A Uyghur Poet's Memoir of China's Genocide

by Tahir Hamut Izgil

When I walked into his store, he was busily packing the radios displayed on his shelves into their boxes and stacking the boxes in large cartons. After we greeted each other, I asked what he was doing. "The police station called," he said bitterly. "We're to gather up all the radios in the store. From now on we're not allowed to sell radios."

It seemed the list of banned items had grown still longer. A few years earlier, the government had banned matches. Rumor had it that the state was trying to prevent separatists from fashioning explosives out of the sulfur in match heads.

That was the end of my plan to purchase a radio. A few days later, I heard that police had begun confiscating radios from people's homes, first in the villages, then in the cities.

It seems the radio era is coming to an end, I said to myself.

I was born at the very end of the 1960s in a poor, unattractive little settlement on the northwestern edge of the Taklamakan Desert. This settlement was a production brigade in the Peyzawat Land Reclamation Sector, which belonged to the third division of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps. The production brigades in the sector were situated several kilometers from one another; traveling between brigades meant a trip down dirt roads through the desert. Residents lived in simple, identical mud-brick homes provided by the government. When there was tilling and harvesting to be done, members of the brigade worked collectively in the wide fields surrounding the settlement. These fields were newly reclaimed land. Carrying their mattocks on their shoulders, brigade members would walk together to the fields. Salaries were equal. Food-primarily corn flour-was provided according to quota. Meat, oil, rice, vegetables, fruit, and wheat flour were precious commodities. Sometimes we would go months without seeing sugar.

Where we lived, the most prized possessions were bicycles, wristwatches, and radios. A radio was the most important means of understanding the outside world and the leading source of entertainment. Each radio had chrome casing and a belt to hang around your neck. Men would strap on their wristwatches, seat their wives on the backs of their bicycles, and turn up the volume on the radios hanging around their necks as they rode to and from the bazaar. These were their happiest moments. My mother and father would ride like that to the bazaar, and in the evening would bring me back a round girde roll made from real wheat flour-not that coarse corn flour we always ate-and four or five candies. I would be the happiest kid in the world.

My father's beloved radio usually hung from a post in our house. No one was allowed to touch it. We listened to the state's propaganda news items, the weather reports that were always wrong, and the songs praising the party. My mom would hum along to the songs as she did housework.

The neighborhood kids would take apart old broken radios. We looked with fascination at the parts, unable to imagine how sound could emerge from them. It was the magnet behind the speaker that interested us most. We liked to remove the magnet and use it to find nails we buried under the sand. The magnet's iron-pulling magic amazed us.

From WAITING TO BE ARRESTED AT NIGHT: A Uyghur Poet's Memoir of China's Genocide by Tahir Hamut Izgil, translated by Joshua L. Freeman. Copyright © Tahir Hamut Izgil, 2023. Published by arrangement with Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Random House LLC.

From Waiting to Be Arrested at Night: A Uyghur Poet's Memoir of China's Genocide by Tahir Hamut Izgil by Tahir Hamut Izgil, translated by Joshua L. Freeman. Copyright © Tahir Hamut Izgil, 2023. Published by arrangement with Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Random House LLC.

The purpose of life is to be defeated by greater and greater things.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.