Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

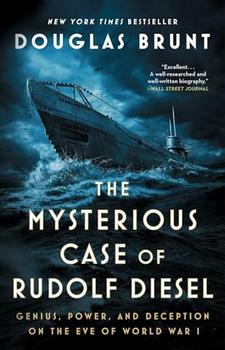

Genius, Power, and Deception on the Eve of World War I

by Douglas Brunt

The Diesel engine didn't require hours to boil water. It operated immediately from a cold start. Nor did it require teams of men to stoke the fires, but simply drew liquid fuel automatically from a tank. The compact engine had no boiler, no furnace nor chimney apparatus at all. Diesel burned a viscous fuel that had no fumes, was safe to store, and the engine consumed its fuel so efficiently that a ship could circumnavigate the globe without stopping to refuel, and it did so with no discernable exhaust to give away the ship's presence on the horizon. What's more, the fuel for a Diesel engine came from the natural resources that were abundant nearly everywhere. Diesel's design was a quantum leap forward in humankind's ability to convert a substance into power. His engine became the most disruptive technology in history.

Diesel intended for his compact, safe, and efficient engine to lift up rural and urban economies alike, to do the work previously done by the backs of men, to advance the quality of life for all. But his intention was not to be.

When Rudolf Diesel went missing in 1913, the major newspapers from New York to Moscow ran front-page stories about the great scientist's disappearance. Though suicide by drowning was the working theory, the press also advanced the theory of foul play, and named two of the most famous men on the planet as the prime suspects.

One theory pointed to the German emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, and his agents, hypothesizing that the kaiser was so enraged by Diesel's rumored business dealings with the British that he had ordered the inventor's murder. One headline read, "Inventor Thrown into the Sea to Stop Sale of Patents to the British Government."

The other high-profile person who some suggested could be behind Diesel's death was the world's richest man, John D. Rockefeller. Rockefeller and his cohorts viewed Diesel's revolutionary technology—an engine that didn't require gasoline or any product derived from crude oil—to be an existential threat to their business empires. Another headline claimed that Rudolf Diesel was "Murdered by Agents from Big Oil Trusts."

In death, Rudolf Diesel, the genius inventor, was at the center of a great mystery. Only one year earlier, in 1912, major figures on the world stage had lauded the emergence of Diesel's game-changing technology. Thomas Edison pronounced the Diesel engine "one of the great achievements of mankind." Winston Churchill, an early admirer and advocate of Diesel motors, declared a new class of Diesel-powered cargo ship to be "the most perfect maritime masterpiece of the century." Now Rudolf Diesel, the man whom the famed British journalist W. T. Stead described in 1912 as "the great magician of the world," was gone.

In an industrial age nothing moves without a motor. It is the beating heart of nations, and no inventor was more disruptive to the established order than Rudolf Diesel. The terrible irony is that Rudolf Diesel abhorred the societal evolutions that his engine wrought. He opposed economic centralization to urban centers, he despised global dependence on the oil monopolies, and he loathed mechanized warfare. His aim from the start had been to invent a compact and economical source of power to revitalize the artisan class and liberate the factory workers of the Industrial Age. He envisioned an engine that burned the natural resources that nearly all countries possessed, and did so cleanly, ridding the earth of smogging pollutants.

The story of Rudolf Diesel's effort to change the world is one of the most important of the twentieth century, yet most people know little about it. His engine has persisted and thrived through the decades, and incredibly, the fundamental concept of the engine's design is practically the same today as the engine Rudolf first unveiled in 1897.

But the man seems deliberately scrubbed from history, so much so that Diesel is often misspelled with a lowercase "d." When has Ford been spelled with a lowercase "f"? Chrysler or Benz?

Excerpted from The Mysterious Case of Rudolf Diesel by Douglas Brunt. Copyright © 2023 by Douglas Brunt. Excerpted by permission of Atria Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

They say that in the end truth will triumph, but it's a lie.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.