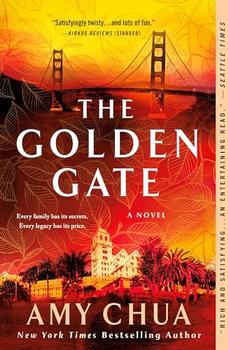

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

by Amy ChuaChapter One

1930

Inside an alabaster palace one January afternoon in 1930, a six-year-old girl hiding inside a closed armoire felt truly alone for the first time in her life.

Just seconds earlier, Issy, short for Isabella, had been in that tingly state of anticipation, half-excited, half-fearful, awaiting the moment when the door would be thrown open and she would be found by her sister, Iris.

Issy loved these special Sundays, when she and Iris and Mommy would put on their nicest dresses and go to the White Palace, where Mommy would change into her all-white skirt and stockings and bandeau and play tennis with her best friend, Mrs. von Urban. On those days, Mommy was always beautiful and nervous in a giggly way, and smelled a little different. She would give the girls the whole afternoon off, and while she and Mrs. von Urban had their tennis game, Issy and Iris would have the run of the hotel, which Iris, the older of the two by eighteen months, seemed to know like the back of her hand, yet there was always more to discover—secret stairways, the seven-story spiral slide, hidden turrets, ballrooms that appeared out of nowhere.

Iris with her jet-black curls and Issy with her blond ones did everything together. Issy couldn't remember a day of her life when she hadn't been with her older sister, which is why until this moment she'd never felt alone.

But now, suddenly, she did. She was curled up in a ball, arms around her knees, in the bottom quarter of a decorative armoire in a long hallway. It was a clever hiding place, but not her best. Iris should have found her by now. Issy should have been able to hear her sister's light limping steps, one foot just a little heavier than the other, or her sing-song whisper, "I'm going to find you! I know where you are!" Instead everything was silent. Issy's legs were starting to stiffen. She didn't know it, but she'd been in the armoire for almost thirty minutes.

She pushed open one of the doors and, seeing that the hallway was empty, stepped out. The palace no longer felt right. Even the silence sounded different from other silences she'd known.

She made her way back to the hotel lobby and went to their palm tree—the spot they'd designated in case they lost each other. The lobby was bustling as always with men looking smart in their fedoras, bellboys overloaded with suitcases, women in pearls and fur collars—but Iris wasn't there.

Issy went next to the tennis courts even though she knew her mother wouldn't be there either. She checked all the courts, with their soft red clay and balls flying through the air and grown-ups running back and forth. There was no Mommy to be found, and Issy felt even more alone.

The little girl returned to the lobby, checked the palm tree again, then decided to go down to the enormous kitchens in the basement. She knew Iris loved the kitchen, its chaotic order, the steaming vats of soup on the stove, the loaves of bread on metal trays sliding in and out of the ovens, and the frenetic brigade that made it all work—chef, sous-chef, and pastry chef; bread bakers and potato peelers; waiters, porters, and dishwashers. Issy saw all of them that day, as well as the egg man delivering his crates, the milkman delivering his jugs, and the hooded man who delivered honey. She didn't know why, but suddenly she felt a scream welling up inside her.

That's when she heard the actual scream—a woman's scream of terror.

For a moment the kitchen froze. Lips and hands stopped moving; no one took a breath. Then the entire staff ran in the direction of the awful sound, overturning carts and knocking plates to the floor, oblivious to their shattering. Issy followed them, dread rising within her.

A crowd had gathered in a low-ceilinged concrete passage near the laundry bins. The air was heavy here, steamy, oppressive. Issy wove her way numbly, without will or thought, past knees and hands; she was so small no one even noticed her. She finally broke through to the front line, where a circle had formed around a pile of soiled sheets and towels on the floor, the effluvium ejected from eight floors of laundry chutes. It smelled carnal, of sweat and other human fluids.

Copyright © 2023 by Amy Chua

Excerpt from "A Peck of Gold" by Robert Frost from The Poetry of Robert Frost edited by Edward Connery Lathem. Copyright © 1928, 1969 by Henry Holt and Company. Copyright © 1956 by Robert Frost. Reprinted by permission of Henry Holt and Company. All Rights Reserved.

"The Death Baby" from The Death Notebooks by Anne Sexton. Copyright © 1974 by Anne Sexton. Used by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.