Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

My Story of the Sea

by Hannah StoweExcerpt

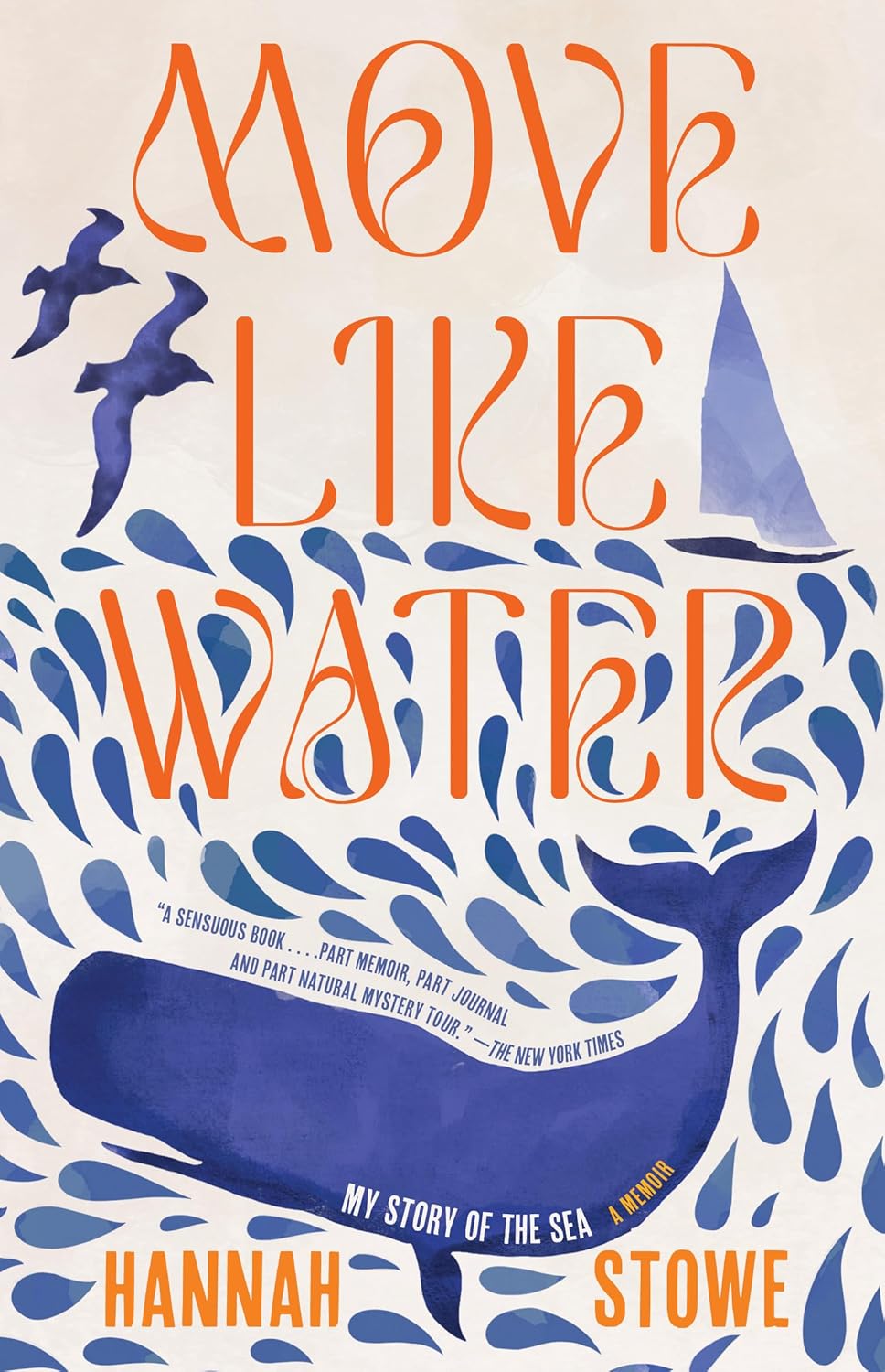

Move Like Water

There was never a time when I did not know the sea. As I lay in my cradle at my mother's feet, day after day, the salt wind blew around our home. It mingled with the honeysuckle that curled around her garden studio, sweet-scented and dappling light as she coaxed gentle worlds to paper with paint. The small, strong oak trees my father had planted when I was born bent and twisted to that wind, framing my world. A hushed roar, water on sand and stone as the tides ebbed and flowed, both rhythm and rhyme. At the start, it was only a lullaby. Throughout my childhood the weather was never far away. At night, I would nestle in my bed, tucked under the eaves in the attic of our cottage, snug next to the chimney breast, fire- warmed, as storms shook the slates from the roof, a ginger cat purring beside me. As I lay awake, I would watch for the beam, the beacon, of Strumble Head Lighthouse as it swept through the night, my companion in the ink hours. In the morning I would scrape the salt spray from the windows, running my finger through its grey- white slick, a quick, sharp taste on my tongue.

That cottage by the sea was a harbour of sorts, a place I always felt safe. It was ramshackle in every way—rendered wall crumbling, paint flaking, wallpaper peeling, furniture clawed by cats and carpets chewed by dogs. The garden was a blend between overgrown and functional, my mother's wild resistance to the manicured lawns on which she was raised. There was a herb garden and vegetable beds, but they weren't always tended. Brambles and alexanders grew in the hedges, and you had to watch for nettles. A great ash tree stood like a guardian at the foot of the path, its leaves lush and verdant. At night, I would often stand under this tree and look up at the night sky with my mother, locating the constellation of Orion, the great hunter with his sword, bow, and belt. There was no reason for Orion in particular, save that those were the stars I was drawn to first. I would stare up at them, fascinated by the celestial light. A con-crete path chalked with hopscotch, crossed and noughted, snaked to the door. Ants would track across it, industrious and purposeful, before returning to their nest opposite the rose bush. Once, when he was visiting us, my grandfather, a contradiction of a man—a naturalist when out walking the Cotswold hills where he lived, naming every bird that winged its way past, every tree, from leaf and bark, as if they were his own family, and yet an enemy to the rhyth-mic chaos of nature in his own garden—threatened to pour pest killer into the ants' mound. The day he left, I reached a small fist up to the kitchen shelf and took a bag of sugar, the bleached granules sparkling in the sun as I poured out a veritable feast in rebellion.

Chickens pecked in the yard, sweet peas climbed canes, and dog roses bloomed. An orange creel buoy hung above the oak front door, the window frames were decayed from salt, and the panes rattled. The weather vane sitting atop the roof was askew, "north" pointing more to north- east than the pole. Inside the house, mountains of books formed dusty labyrinths, the washing- up was usually in various stages of undone, and my ginger cat slept on the mantle above the hearth, looking like Dürer's hare. Find-ing a place on the sofa required delicate negotiation with a collie dog or lurcher. The only source of heat was the fire in the hearth that burned year round. I would sit in front of those flames, a sheepskin rug on the cold slate floor, with pens in my hands, brushes, paper, my raging moods that would often flare turned to paint and ink; even then, I found expression through written word and paint far easier than making myself understood aloud.

There was a current inside me. At times, it swept along straight and true, serene on the surface, but determinedly fast flowing. At others, the winds of life would turn against the tide, steep over falls would whip up in seconds, and I would rage, tempestuous. And sometimes. Sometimes the water flowed to a deeper place. A place where I could still see the light streaking through from the surface, and yet I felt compelled to stay quietly in the dark. This was, this is, my nature. Days and years added length to my limbs, strength to my muscles and all the while, the salt song grew louder. At night, as the light-house beam rotated, roaming both land and sea, I began to wonder how far the light stretched, what was out there in the reaches of that dark. I started to climb the trees, high, high, higher every time, until the branches grew thin and supple, bending under my weight. Higher still, pushing the boundaries of my garden, my range, up into the air, swaying as if in the rig of a ship, until at last there was no canopy left to claim. From the branches at the top, I could see over the roof of the cottage, all the way to the sea. It wasn't long before I started to climb out of the attic- room windows, on to the roof slates themselves for a better view. Once every corner of the cottage, inside and out, had been explored, I started to wander further, venturing past the hedges frothed with blackthorn blossom that bordered my home.

Excerpted from Move Like Water: My Story of the Sea by Hannah Stowe. Reprinted with permission from Tin House. Copyright (c) 2023 by Hannah Stowe.

To make a library it takes two volumes and a fire. Two volumes and a fire, and interest. The interest alone will ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.