Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

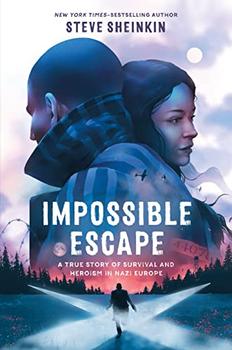

A True Story of Survival and Heroism in Nazi Europe

by Steve Sheinkin

Gerta walked up to her school building—and found the gate locked. She stood outside with a small group of Jewish students, wondering what to do. They'd been attending classes here for years. They knew all the teachers. But when they banged on the gate, the only response came from children shouting:

"Jews out!"

Gerta was shocked to hear this from students. Friends, or so she'd thought.

"As our anger mounted, we felt that we just couldn't leave without some action," Gerta later recalled. She went around to the back of the building, where students left their bicycles, and stuck sharp pebbles between the metal rims and rubber tires of the bike wheels.

This was not very satisfying, Gerta admitted.

"But it was something," she said. "It was a gesture to show that we would not accept without resistance what they did to us."

* * *

Jewish students were even ordered to turn in their school books. This was particularly painful for Rudi. He dropped off his textbooks and walked away, "glum and empty-handed," as he'd later say.

A friend of his, Erwin Eisler, came up beside him and whispered: "Don't worry. I've still got that chemistry book."

Rudi was impressed by this act of defiance. Grateful too; chemistry was his favorite subject. The two friends studied together when they could, sharing the forbidden text in the privacy of their homes.

Rudi turned fifteen that September. He kept himself busy by building a chemistry lab in a shed in his mother's garden. Gerta was among the friends who came over to visit Rudi's lab. He took contagious pleasure in explaining his experiments, describing why different substances changed color or texture when combined.

When he could find jobs, Rudi worked as a laborer. At night he studied at home, teaching himself Russian in the family living room. He had a knack for languages and a prodigious memory—he already spoke Slovak, Czech, Hungarian, and German. Rudi's mother teased him about his studies. What was a Jewish boy from Slovakia going to do with Russian?

She could never have guessed how it was going to help him.

* * *

On warm evenings, before curfew, Rudi, Gerta, and their friends met in a meadow outside of town. They'd sit together in the tall grass and talk about books and politics, about the terrifying state of the world and what they'd do if they were in charge.

Gerta found herself falling for Rudi. "He had a round, friendly face and a winning smile," she'd recall. Rudi was always happy to tutor Gerta in math and science, but he didn't seem to return the crush. She'd later find out that he was embarrassed by a hat she sometimes wore, which had a pom-pom and made her look, he thought, like a little kid.

"It is strange," she'd reflect. "Faced with all the really serious problems we had, we could nevertheless be affected by the same emotions as normal teenagers."

The teens' parents seemed to think Slovakia's surge of antisemitism would blow over. But to Rudi and Gerta's group of friends, this felt like more than a passing storm. Their Christian friends, kids they'd joked around with for years, wouldn't even look at them anymore. People threw bricks through their windows, scrawled "Jew" on the walls of their homes. Members of the Hlinka Guard—modeled on Hitler's dreaded SS—marched around in black uniforms and shiny boots, beating anyone they felt like beating.

Gerta told the group about the non-Jewish "adviser" assigned to her parents' butcher shop—Mr. Šimončič, the father of her former friend Marushka. The man openly robbed them. Far more chilling to Gerta was his utter lack of the slightest hint of shame.

As if all of this was perfectly normal.

"It will not be long now," he said to her, "and all of you will be gone."

* * *

Adolf Hitler's forces invaded western Europe in the spring of 1940, quickly overrunning Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and France. Hitler turned east in June 1941, launching a massive attack on the Soviet Union. Millions of German troops drove deep into Soviet territory.

Excerpted from Impossible Escape by Steve Sheinkin. Copyright © 2023 by Steve Sheinkin. Excerpted by permission of Roaring Brook Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The worth of a book is to be measured by what you can carry away from it.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.