Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

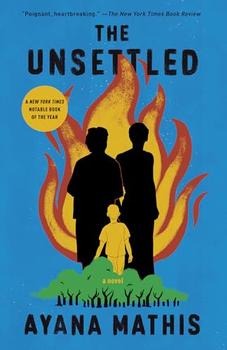

by Ayana Mathis

"Ma, you want me to hold it?" Toussaint asked. Ava couldn't balance the clipboard against the wall and the papers kept slipping to the floor. Her boy put his hand on her arm. His eyes were big as plums and flitted from one thing to the next: a nut-brown baby slung over a shoulder, a little girl who kept undoing her barrettes till her mama popped her one, a lady shaking her papers at the intake man. Ava swallowed back another wave of sick and focused on the forms.

The forms had questions like: Last address. 245 Turnstone Pike, James Creek, New Jersey. Next of kin. N/A. Marital status: Married. Separated. Emergency contact: N/A. What circumstances led you to seek assistance at Homeless Services? Two weeks ago, my husband Abemi Reed threw us out of our home his home in New Jersey.

Then she wrote: Last night me and Toussaint were sitting on a bench in a bus shelter across the street from a lady's house out in the Northeast. She had a pitcher of iced tea on her table. It was dark in the bus shelter, then the streetlight came on right over us and we were lit up. That woman in her kitchen saw us so I didn't think we should stay there. And we were so tired. I spent nearly all the money on a motel. In the morning my son asked where we'd go after we left there. Are we going to spend the night here again, is what he said. I got him an egg sandwich at the McDonald's down the street. We sat in the air-conditioning and watched some kids on the slide in the Playland. I had put aside enough for bus fare, so that no matter what, we could get somewhere. We used the bus fare and came here on the El.

Ava ran out of space and had to write down the margins. She knew that wasn't the kind of answer they wanted, but she had to tell somebody. The man at the intake window was talking on the phone and didn't even look up when she pushed the clipboard through the slot. She stood with her arms at her sides and waited. After some time, he glanced up at her and sighed.

"Come on, miss. Take it easy." He picked up the clipboard. "You can't cry in here. You need to calm— Gloria! Come out here cause this lady is . . . Don't put your hands all on the glass, miss."

Gloria was noisy coming out of a side door: "Okay. You got to be easy or we can't . . ." But it wasn't just Ava—half people in there were crying, or trying not to. Wouldn't any of them look each other in the eye though.

Gloria assigned Ava and Toussaint to the Glenn Avenue Family Shelter. She gave them carfare—tokens and paper transfers, not cash. Three hours later they were back out on the street. The skinny-boughed Center City trees drooped in the heat, and the business ladies' hair-sprayed dos were limp. Ava and Toussaint dragged their suitcases and trash bag down Broad Street to the subway. They took turns hauling their things down the subway stairs: Toussaint guarded the stuff and Ava took two suitcases down. Then switch. Then switch. People stared but nobody helped. A dark collar of sweat spread around Ava's neck. Toussaint's eyes were glazed and his lips were whitish and dry. The other passengers kept their distance, even though they were sweating too, even though some of them were taking up too much space with shopping bags and laundry carts. People are funny like that.

Ava and Toussaint got off the subway, took two buses, and at last found themselves trudging through the streets with their bags. The directions said walk four blocks to Tulpehocken. Turn left. They walked five blocks, then six. Mosquitoes buzzed in their ears.

"Ma? Ma! Is this it?" Toussaint asked of every building they passed.

They arrived at an intersection. Around the corner, a one-story gray building sprawled in the middle of the block, big and sad-looking the way government buildings are. There was a tumult in the U-shaped driveway in front, and a tangle of women and children; so many you'd think kids and mothers were the only people bad things happened to. Some of the mothers needed to take out their rollers, and some of the kids had stained T-shirts, and some of them needed haircuts. Ava didn't notice the boys with their pants neatly ironed or the women with their hair and nails done up nice. All she knew was she couldn't walk in there. But Toussaint was slumped against a tree. He couldn't take another step, or not many more.

Excerpted from The Unsettled by Ayana Mathis. Copyright © 2023 by Ayana Mathis. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Poetry is like fish: if it's fresh, it's good; if it's stale, it's bad; and if you're not certain, try it on the ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.