Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

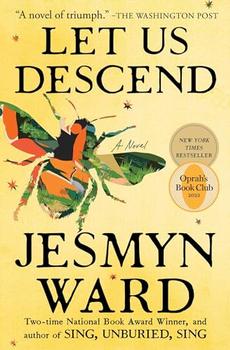

by Jesmyn Ward

I take care to hide from his gaze. It is something that I have always known how to do: I seal my mouth silent. As the day lengthens, I walk on tiptoe through the wide, dim halls of my sire's house. I set buckets and basins down softly, ease the metal to the floor in a ring. I stand very still, just beyond the doorway of my pale sisters' schoolroom, and listen to their tutor read to them beyond the door. The stories I hear are not my mother's stories: there is a different ringing, a different singing to them that settles down into my chest and shivers there like a weapon vibrating in struck flesh. These girls, sallow sisters, read from the texts their tutor directs them to, ancient Greeks who write about animals and industry, wasps and bees, and I listen: "Bees seem to take a pleasure in listening to a rattling noise; and consequently men say that they can muster them into a hive by rattling with crockery or stones." The youngest sister's voice falls to a mumble and rises. "They expel from the hive all idlers and unthrifts. As has been said, they differentiate their work; some make wax, some make honey, some make bee-bread, some shape and mold combs, some bring water to the cells and mingle it with the honey…" I breathe in the pine halls and repeat the most potent words: wax, honey, bee-bread, combs.

"Aristotle refers to the heads of the hives as kings," the tutor says, "but scientists have found they are female: actually queens. In ancient Greece, Artemis's priests were known as 'king bees.' Bees, too, were credited with giving the gift of prophecy to her brother Apollo." The tutor gives a dry laugh. "This is blasphemous superstition. However, Aristotle's advice on those who labor and the fruits of that labor are sound: leave a hive with too much honey, and a beekeeper encourages laziness," he says, his voice high and soft, nearly as soft as those of my unsure sisters. I know he is speaking about bees but not—that he is using the bees and the old Greek to speak on all of us who labor. I know he's talking about my mother making biscuits and stews on the stove in the attached kitchen, about Cleo and her daughter Safi and me, who tidy rooms, beat dust from rags, wipe their floors until they gleam like burnished acorns.

I hurry downstairs to my mother, who reads me as quickly as the tutor reads his passages.

"You've been listening again?" she asks.

I nod.

"Have care," she whispers, and then bangs her spoon on a black pot. The kitchen is thick with salt meat. "He wouldn't take kindly to knowing."

"I know," I say. I want to tell her more. I want to tell her that I envy my sire's twin daughters, their soft shoulders, their hair pale and thin as spider's silk, their lessons, their linens, their cream-colored, paper-thin dresses. I want to tell her that when I listen at their doors, I am taking one thing for myself, one thing that none of them would give. I say the tutor's words in my head again, trying not to feel guilty at my mother's worried frown, the way her anxiety makes her stab her spoon into the pot. Wax, honey, bee-bread, combs. How to apologize for wanting some word, some story, some beautiful thing for my own?

"I'm sorry, Mama," I say as I retreat outside to gather more wood.

A lone bee meanders through the kitchen garden: plump, black striped, beautiful. It lands on my shoulder, soft as a fingertip, and I wonder what message it brings, from what spirit worlds. They are queens, the tutor said. When the bee rises and disappears into a nodding yellow squash flower, wind beats through the trees, and I think for a moment I hear an echo drifting down through the branches: Queens.

WHEN I TURN DOWN my sire's bed, he watches from beside the cold fireplace. Normally, he is downstairs, sipping amber drinks and visiting with other planters, all buttoned-up vests and murmured conversation punctuated by bluster. Tonight, he sits in an upholstered armchair, part of his dead wife's dowry. At dinner, he complained of fever and congestion, and asked my mother for a remedy: a mixture of mushrooms and herbs. It is this I set before him in a ceramic cup. He holds the cup with two fingers, his legs long before him, his boots caked with spring mud. His eyes shine with the light of the candles, and I look at my hands: smoothing, plumping, folding. I will myself to move faster so I can get out of this room and into the moonlit night.

Excerpted from Let Us Descend by Jesmyn Ward. Copyright © 2023 by Jesmyn Ward. Excerpted by permission of Scribner. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.