Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

I cut the twine with my fruit knife, inserted its tip into a fold of the wrapping and with two or three brisk strokes filleted the package open. The corner of a book appeared. I peeled away the wrapping until the title revealed itself: The Casuarina Tree by W.Somerset Maugham.

There was nothing else in the package – no letter, no note. I turned the book over in my hands. Robert collected first editions, and he had all of Willie Maugham's books – his novels and his short-story anthologies, the plays and the essays. It crossed my mind that this volume in my hands was a first edition too, the colours of the tropical trees and the blue sky on its dustjacket already faded.

The table of contents listed half a dozen stories. I thumbed the pages to the last one. Murmuring the story's opening paragraph under my breath, I found myself instantly transported back to Malaya. I felt a heavy tropical heat smothering me, thick and steamy, and the pungent, salty tang of the mudflats at low tide clogged my nostrils.

I checked the title page, but there was no inscription, nor a signature. Printed underneath the title was the arcane-looking glyph Maugham placed in all of his books. This particular one, however, was slightly different: some unknown hand had drawn a thin, black vertical rectangle around the symbol, enclosing it in the centre. Running from top to bottom was another straight black line, bisecting the frame precisely in the middle.

I frowned, puzzled.

An instant later I saw it, I understood what the lines were telling me. Carefully, as though fearful that any sudden movement would dislodge the rectangle around the symbol, I set the book down on the table. The open page arched slightly in a passing breeze, then flattened out again. I leaned back in my chair, my gaze fastened on the glyph, this anchor embedded in the paper.

Robert and I had uprooted ourselves from Penang at the end of 1922, sailing on a P&O liner to Cape Town. We stayed a pleasant fortnight in a hotel by the sea before taking the train to Beaufort West, a little town three hundred or so miles to the northeast. Bernard, Robert's cousin, was a sheep farmer, and he had built us a modest bungalow on his land. The bungalow, whitewashed and capped with a corrugated tin roof painted a dark green, stood on a high broad ridge. From the deep and shady verandah – I would never get used to the locals calling it a 'stoep', I told myself – we had an unbroken vista of the mountains to the north. These mountains had been formed by the dying ripples of the earth's upheavals an eternity ago, upheavals that had begun far to the south at the very tip of the continent.

It was high summer when we arrived, the sun smiting the earth. Everything was so bleak – the parchment landscape, the faces of the people, even the light itself. How I ached for the monsoon skies of the equator, for the ever-changing tints of its chameleon sea.

A week after we had settled into our new home we were invited to the farmhouse for dinner. The sun was just burrowing into the mountains when we walked the half-mile there from our bungalow. We had to stop a few times along the way for Robert to catch his breath. Bernard Presgrave was thirty-eight, twelve years Robert's junior. Robust and ruddy-faced, he reminded me of Robert when I first married him. His farm was called Doornfontein, the Fountain of Thorns, the kind of inauspicious name that would have set my old amah Ah Peng muttering darkly, 'Asking for trouble only.' But Bernard and his wife Helena, a placid and dull girl from the Cape, appeared to be prospering.

The other guests – farmers and their wives from around the area – were already gathered in the straggly garden behind the farmhouse when we arrived. We joined them in a circle beneath a camelthorn tree, its bare branches spiked with thin white thorns as long as my little finger. The laughter and shrieks of the children playing at the bottom of the garden rang across the evening air. A pair of oil drums, cut open in half, rested on trestles, wood fire lapping away at their insides. Lamb chops and coils of sausages were smoking away on the grill. The farmers were Boers, blunt-faced and blunt-spoken, but affable once we got to know them. The meat of the gossip that evening – and chewed over and over into gristle throughout the district that summer, I would discover – concerned a wealthy middle-aged Englishman and his beautiful young wife who had moved to Beaufort West from London the previous summer.

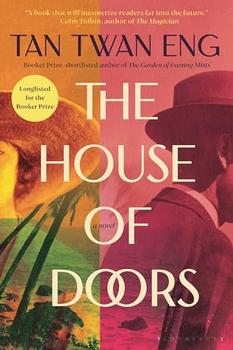

Excerpted from The House of Doors by Tan Twan Eng. Copyright © 2023 by Tan Twan Eng. Excerpted by permission of Bloomsbury Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.