Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

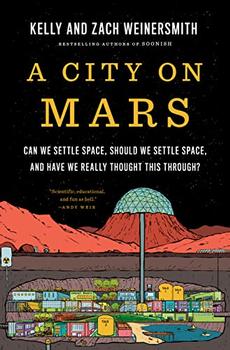

Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through?

by Kelly Weinersmith, Zach Weinersmith

A related idea is that space should be zoned for heavy industry, while Earth returns to an unpolluted Edenic state. All the nasty mining and manufacturing can be done elsewhere, with by-products cleanly disposed of into the vast landfill that is the solar system. As Jeff Bezos says, "Earth will be zoned residential and light industrial." Again, this is literally possible, and perhaps as long as you're just thinking in terms of big concepts like pollution and mass it sounds doable. But the details are where the difficulty lives. Consider for example cement. It's a major contributor to global warming, so can we make it in space?

Technically, most of the components of cement by mass exist on the Moon, but they won't be easy to dig up. Construction equipment will need to be built to function in an airless environment at low gravity with equatorial temperature swings from -130°C to 120°C. Little things start to loom in this context. Just getting a lubricant that can handle these temperature shifts without degrading is nearly impossible. The same goes for the machines themselves. At extreme cold some metals can undergo a ductile-to-brittle transition; below a certain temperature, metals behave more like stone. However strong they may be, they can't flex and bend. It's speculated that the Titanic sank because its steel hull experienced a ductile-to-brittle transition before hitting the infamous iceberg. That's a nontrivial problem when you desire to use construction equipment that regularly slams into hard surfaces.

And that's just one detail of one part of the process, never mind replicating all those factories. How soon can we plausibly get all these problems solved and then scaled to the needs of Earth, which currently requires over 3.5 billion metric tons of cement per year? And does it sound economically competitive with Earth-made cement even if we could do it? And, by the way, what are the rules for dropping 3.5 billion tons of rock on Earth annually?

Part of what's supposed to make these ideas work is cheap, plentiful energy thanks to space-based solar power. This is another bad idea. Space-based solar power figures prominently in space-settlement proposals for giant rotating space stations. It's also frequently proposed by governments and private space companies as a way to make money while greening the planet. You may have read an article recently about Chinese universities or the European Space Agency, or some new start-up planning to field this technology in the near future. They probably shouldn't.

It's certainly true that there's a whole Sun's worth of sunlight in space, unobstructed by annoying Earth features like weather and the atmosphere. Exactly how much more energy you might get per panel depends on exactly what assumptions you're prepared to make, but different estimates expect about an order of magnitude improvement. That sounds like a lot until you ask yourself what the cost differential will be between a panel in space and a panel in Australia.

It's conceivable that in a world where solar panels are incredibly expensive and there's an extreme collapse in the cost of launching objects to space, you might want to maximize your energy per panel by putting them above the atmosphere. But panels are cheap, and even if we assume pretty steep drops in the cost of space launch, the numbers don't add up. This becomes especially clear when you start to think about maintenance. Try to imagine acres upon acres of glass panels in space, regularly pelted by intense radiation and bits of space debris while enduring the extreme heat of perpetual sunlight. They'll have to be repaired and cared for either by astronauts or an army of advanced robots. Solar panels in Australia can be cleaned by a teenager with a squeegee.

When dumping solar power back to Earth, you have another problem. Solar panels on the ground can send their power right into the grid or to batteries. Space-based power has to be beamed to huge receivers on Earth, losing energy en route. But it can't be beamed at too high an intensity, lest it endanger birds and planes.

Excerpted from A City on Mars by Kelly Weinersmith and Zach Weinersmith. Copyright © 2023 by Kelly Weinersmith and Zach Weinersmith. Excerpted by permission of Penguin Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.