Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Notes on the Science of Life

by Nell GreenfieldboyceIntroduction

For nearly thirty years, I have made my living by writing about science. Much of that time has been spent working for National Public Radio (NPR). I usually produce two--to--eight--minute audio stories that are designed to inform or delight: neat, tidy sonic tales that convey news about, say, the color of dinosaur eggs, or possible signs of life on Venus, or sharks that swim for centuries beneath the Arctic ice. A workday might involve chatting with a researcher who studies carnivorous plants or flying snakes or gravitational waves that roll through the fabric of space-time. To report my stories, I've climbed into one of NASA's space shuttles (on the ground, thankfully) and onto a boat that was hunting for a Civil War–-era submarine. I've gone down into a coal mine, where deafening machines ripped black rock from the Earth's crust, and into the control room of a particle collider, where magnets accelerated beams of tiny particles to almost the speed of light, smashing them together so that scientists could pick through the subatomic rubble.

When I became a parent, I suddenly had a new audience. A much smaller audience—only two, instead of millions—but with higher emotional stakes. With my son and daughter, I generally tried to err on the side of staying silent instead of sharing a thought or observation or memorized fact. Whatever I might say seemed unnecessary and often unequal to their own powers of perception. The child-as-scientist has become a cliché, but I marveled at my children's relentless exploration, their intense focus, their ruthless experimentation, their admirable lack of preconceptions. One morning, for example, when my son was about two and a half years old, I woke up and came downstairs to find the refrigerator door open and my son sitting inside the fridge, on an interior ledge, facing the shelves full of condiments. "Are you finding anything interesting in there?" I asked (ignoring the panic synapses that clanged child in a refrigerator, danger! danger! ). He said, "I'm trying to open this. What is this?" He held up a stick of butter. I took it, partially unwrapped it, and handed it back. He bit into it thoughtfully, then dug his little fingers into it and pulled off a greasy lump, saying, "Here is some butter for you." I was touched by this gesture, his desire to include me in the moment of discovery.

What I do tell them often proves useless, and unconvincing. When my toddling daughter scraped her knee and I offered to kiss her boo-boo, she said, not unkindly, "That won't do anything. Can I have some ice?" Later, I tried to convince her to go to bed on the night before vacation by telling her that the sooner she went to sleep, the sooner it would be morning, when we would leave for the beach. "Whether or not I go to sleep is not going to affect how fast time goes," she replied. My efforts to console her as she cried over a broken teacup from her tea set also were futile, but then her brother cheerfully informed her that "actually, everything is going to break. Even the whole universe is going to end!" She nodded at this and began to dry her tears. "And the sun will burn out," she said.

I never planned to write about private scenes like this; I kept my job as a science reporter separate from my life at home. But about a decade ago, a large spider spun a web in the corner of our kitchen window frame, and I grew to care for it. My friend and mentor, the science writer Ann Finkbeiner, encouraged me to write about this spider for a blog run by science journalists called The Last Word on Nothing. The blog's name comes from a quote by Victor Hugo: "Science says the first word on everything, and the last word on nothing." A number of professional science writers who want to break out of their routine use this blog as a creative sandbox (the blog's unofficial motto: "we write about whatever the &*%#$ we want"). I hadn't written a personal essay before. It felt risky. A reporter traditionally remains somewhat anonymous, and I had been a reporter for more than half of my life. I wasn't sure I wanted people to know what I thought about in my kitchen while I watched a spider. But once I wrote that piece, I began to write about other personal experiences, too—including ones that were more fraught.

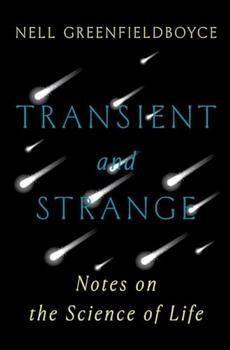

Excerpted from Transient and Strange by Nell Greenfieldboyce. Copyright © 2024 by Nell Greenfieldboyce. Excerpted by permission of W.W. Norton & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed people can change the world...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.