Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The primary difference between these linguists and DSOs is one of location. DSOs don't fly on RC-135s, or any similar massive aircraft. DSOs fly exclusively on the planes that are utilized by Air Force Special Operations Command, or AFSOC. For the most part, these are C-130s that have been modified for various purposes. Some of these, like the AC-130s, or gunships, have been changed so much from their original cargo-carrying mission as to be unrecognizable; the only cargo a gunship carries is bullets. Others, like the MC-130s, still can and do carry cargo, but they've been made to be better at doing it. AFSOC has other aircraft that DSOs are trained to fly on, but in my time in Afghanistan, we almost exclusively flew on C-130s. Timing is the other thing that makes a DSO's work different from that of other linguists. AFSOC doesn't do strategic work all that often, and so neither do DSOs. In Afghanistan, our job was to "provide real-time threat warning" to the planes we were on and to the people on the ground that these planes were supporting. How we did this work is unimportant, and honestly quite boring. I don't know if they still think of themselves as badasses, but when I was a DSO, that was the ethos of the community. We (not all, but most of us) felt that we were the best of the best: better than other linguists, cooler than other linguists, more important than other linguists. Once upon a time, some of this may have been true. Long before I did it, in order to be a DSO you had to be very good at the language(s) you spoke, and you had to be handpicked by other DSOs, interviewed, and tested; it was a whole process. And there were those DSOs who flew scary, com- plex missions in dangerous places. But by 2010 the Air Force just randomly assigned new linguists to become DSOs, and the thing most likely to take down the aircraft a DSO was in was a drone (seriously, they have a bad habit of losing connection and orbiting at preselected altitudes that are, let's say, inconvenient for other, human-containing aircraft).

But the DSO told himself that he was a badass. An elite, spe- cialized, and superior human who had earned the right to do what he did purely on merit, and to shit on others who hadn't earned the same opportunity. You may recognize this story, as it's the same story most small men tell themselves. The DSO, for obvious reasons, did not realize this.

If I sound petulant, obstreperous, dismissive, arrogant, or, you know, just like a fucking dick, that's fair. I have a strong dislike of those who consider themselves Better Than, and that dislike turns into utter contempt when this shameless self-promotion is founded on false pretenses that rely on the diminishment of others. This is somewhat a reaction formation, given that I spent my childhood, adolescence, and a decent amount of my young adulthood committing this very sin, and I continue to feel great shame about it. That doesn't mean that I'm not right. I am. Being a DSO does not make you particularly special. It doesn't make you better than anyone else, especially other linguists. And ultimately, like most things, it isn't all that important.

But it really is spectacularly, mind-blowingly, worldview- changingly awesome. I mean like, biblically awesome. A DSO is no god (the new gods are as dead as the old), but he is sometimes powerful beyond comprehension. Providing "real-time threat warning" is a very bland way of saying that I listened to the Tal- iban as they were talking (essentially with no delay), translated it from Pashto to English, and relayed that information to my crew, to other planes, or to forces on the ground, often within seconds. If I was on a gunship, what I heard would be used to decide whether we killed those Talibs. If I was on a different type of C-130, what I heard could force us to take evasive maneuvers, to try and keep us from getting shot by those Talibs. Either way, I would temporarily be responsible for a hundred-million-dollar war plane.

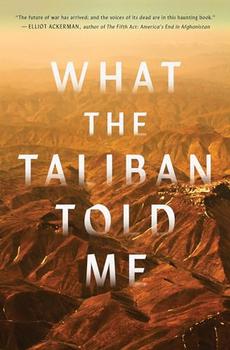

Excerpted from What the Taliban Told Me by Ian Fritz. Copyright © 2023 by Ian Fritz. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Wisdom is the reward you get for a lifetime of listening when you'd rather have been talking

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.