Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

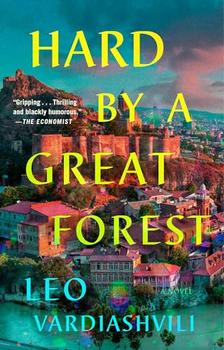

by Leo Vardiashvili1

WHERE'S EKA

"Where's Eka?" We must have asked a thousand times.

Our mother stayed so we could escape.

See, war trumps most things. You'll find that a volley of AK‑47 rounds fired right down your street will override almost any other concern. We heard gunfire by night and saw brass twinkling on the pavement in the morning, as though it had rained shell casings all over Tbilisi. Sounds manageable so far.

But when a stray tank shell breaks the sound barrier by your bedroom window, screams on, and deletes the corner grocery shop and the entire family living above it, you'll begin to make plans. Our parents, Irakli and Eka, made plans to get us all out, divorce be damned.

Getting out of the country meant shady bribes, stolen travel stamps, and counterfeit certificates. What money the family scratched together was barely enough for one parent and us children. Eka didn't even have a passport. Together we couldn't leave the country.

Meanwhile, the civil war was warming up, bullet holes in familiar places and people no longer a surprise. We had to go. Eka stayed and we escaped with Irakli.

That's how we became motherless, Sandro and I. I was eight and Sandro was two years older. At that age, the difference was a whole ocean of experience. Even so, Sandro had no inkling of what motherless meant, and neither did I.

There was no fanfare upon our arrival on the capitalist shores of the UK. They put us straight in a refugee shelter in Croydon. In that cold warehouse of bunk beds, communal toilets, and food tokens, nervous faces haunted the hallways.

Eventually, somewhere deep in the guts of the Home Office machine, gears clicked, a screen flickered to life, and we were granted refugee status, with "Tottenham, N17" printed on our case file.

In those early days we floundered in a city we didn't know. Tottenham in 1992 wasn't the London we'd imagined. There were no top hats, no smog, no Holmes, no Watson, no ladies, no gents, and no afternoon tea. Not for us.

We lived in a different London. In our London, people swore and spat, drank, quarreled, and laughed in fretful bursts. They spoke strange words in accents we couldn't parse. They walked bowed by the weight of mouths‑to‑feed, bills‑to‑pay, and how‑many‑days‑till‑payday?

Our da walked among them. Our Irakli—a man out at sea without a compass, searching for a woman he'd managed to lose twice. First, he lost Eka to a divorce shrouded in mystery. Then, to a civil war that reunited and parted them in one breath.

"Where's Eka?"

"Soon, boys. We'll get her back," Irakli would say. A promise not yet a lie.

He broke his back trying to buy Eka a way out. He picked fruit, painted walls, stacked shelves in warehouses, sweated and toiled in nameless, windowless factories across North London.

Those jobs wore him down in subtle, vital ways. We watched him erode. Once, he fell asleep at the table, spoon halfway to his mouth. We laughed and laughed. Sometimes you have to laugh at a thing to strip it of its power.

It's hard to save thousands by pounds and pennies. It's harder to send what you've scratched together to a country on fire. Georgia was eating itself alive—no banks to speak of, no working postal system. Those of us who'd escaped were not exactly keen to go back to a war zone.

Somehow, Irakli found someone willing to fly back there, for a fee. He was a tall, skinny man with earnest eyes. He looked honest and said the right things. Held his cigarette just so. He ate our food and drank our drink. He took the pounds and pennies meant for Eka and left, smiling and shaking hands. For a while, we stopped asking where Eka was.

I don't remember the honest man's name, but in my dreams he's died a thousand deaths by my hand. Eka never got the money and we never saw the honest man again. Irakli drank, and one night from the bedroom we heard him break the coffee table. The next morning, we found the table glued back together and Irakli gone back to work.

Excerpted from Hard by a Great Forest by Leo Vardiashvili. Copyright © 2024 by Leo Vardiashvili. Excerpted by permission of Riverhead Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Life is the garment we continually alter, but which never seems to fit.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.