Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

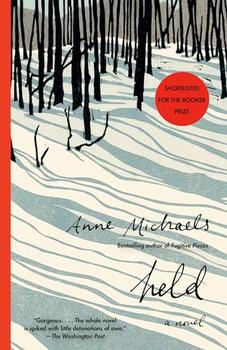

A Novel

by Anne Michaels

Peter had money, but he was not proud of it and he did not want to stop working. He opened a small workshop—surprisingly, men never seemed to stop wearing hats—and he and Anna, newly married, lived above it. They did not want much, and they lived on what they earned, leaving the money from his family's business mostly untouched. It was to be their nest egg, their daughter Mara's inheritance. Peter did not have any inclination to live another kind of life. Anna was in agreement, and she had the freedom to go where she was needed.

* * *

Peter and Mara had a game they played when Anna was away. At first, he had shown Mara the map to soothe her, to make her believe the world was not so large, that her Mama was not so far. "Look—she's here—just a few inches away!" She would touch his finger as he pointed, then touch the place with her own finger, then take her father's big face in her tiny hands.

"Can we telephone?"

"Not yet—where Mama is, it's three o'clock and she's at work."

It took some explaining, but eventually Mara understood: when it was morning where she was, it was after noon where her Mama was. When she ate her dinner, her mother was going to sleep. Soon Mara knew the time zones and could measure her ache for her mother with pinpoint accuracy.

* * *

When Mara was young, she conquered the sewing machine with the natural talent of a draughtsman with a pencil, as adept as the great-grandfather she'd never known. If she saw an apron or a tea towel she liked, she made a skirt; she saved scraps and in twenty minutes was dressed for the opera. Her secret was being unafraid to go freehand, never measuring. Measuring made her nervous, slowed her down. Mara was resourceful, she trusted herself. He knew that was one of the reasons they always asked for her, and one of the reasons she always went. He still joked that if she could, she would carry her sewing machine in her backpack. Maybe, he joked, she came home because she missed her sewing machine. Now, between forkfuls of pancake, she told him she would feel blessed to be able to work in a clinic or an emergency ward. It only took a moment for him to understand. It was a man. She was in love. He never thought he'd be grateful to lose her that way. But someone else had brought her home and Peter was already half-mad with gratitude.

* * *

Her lover was a journalist. As Peter watched his daughter devouring pancakes at the kitchen table, he imagined that Mara had met her man in the hospital, that she had repaired him, that Alan had come out of the anaesthetic and seen her eyes full of kindness. That he had watched her move through the ward, seen how she listened, how she held the gaze or the hand of the shattered men she examined with such gentleness, while she assessed, absorbed information with uncompromised efficiency. That he was fascinated, awestruck. Peter imagined the scene, like cinema.

"Where shall we live?"

"I need to be near my father."

"Then that's where we'll be."

He knew Mara had always thought love made things complicated, but Peter knew love was a sharp blade slicing an apple: cleaved—both blade and bond.

* * *

Mara had been away for weeks, trucked from place to place, boarded wherever there was room, waiting overnight in pick-up locations. The permanent lack of sleep in any other circumstance would have felt like an illness; now it was continuous proof she was still alive.

In the ruins, the smoke chafed the back of her throat, but it was dry and quiet and she slept like a stone. When she woke, she saw him sleeping next to her. Later Alan would tell the story of how he had found her. But she would never forget the feeling that she had found him, simply by opening her eyes.

* * *

After he was flown out, she sobbed for two days. Then she felt scoured; the boulder inside her chest was gone. It had been replaced by emptiness. That was better.

* * *

When he returned home, Alan wrapped the strap around his camera, put it in the bottom of his rucksack and locked the rucksack in a suitcase. He would have thrown the suitcase in the river if he'd had the energy to carry it there. Then he locked himself up too, to seal off his contagion.

Excerpted from Held by Anne Michaels. Copyright © 2024 by Anne Michaels. Excerpted by permission of Knopf. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Show me the books he loves and I shall know the man...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.