Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

They were concerned about being blamed by the police for a thrashed-up foreigner, and they wanted Sunny to take responsibility for me.

But doing so meant he would have had to leave behind his motorcycle, one of the two most valuable things he owned. After a lot of haggling, he offered to follow behind the ambulance, but the crew worried he would race off. So Sunny negotiated a compromise: he would give them his second-most-valuable possession, his smartphone, as a guarantee that he would stay with them until they got to the hospital. Since the phone meant a month's salary to him, he did not give it up lightly.

The driver for the New York Times bureau in Delhi, Jagmohan Singh, had already realized something was wrong when I had not returned within the hour I had promised. Jag, as we all called him, has worked for multiple bureau chiefs over the past 20 years and he remains friends with many of them. He began doggedly ringing the cell phone I had in my pocket until finally someone answered it and told him I was on my way to Moolchand Hospital.

We foreign correspondents depend heavily on our local staff members; they are our interpreters to their societies, our protectors, our surrogate families, and they often become great friends as well. But I was new to Delhi, filling in for our bureau chief, Jeffrey Gettleman, while he was on vacation, so the bureau staff barely knew me.

Nevertheless, as I heard later, half a dozen of them gathered with Jag around my hospital bed, sending an important message in a country where your place in a byzantine social hierarchy can be a matter of life or death. It was, in short, a crucial communication: that this is someone to attend to.

Now the monsoon was upon us with a vengeance. Reflections of lightning flashed across the walls of the intensive care unit, and sheets of nearly horizontal rain beat a tattoo against the windows, with seemingly no spaces between the raindrops.

While I was comatose for a day or two, dozens of people perished from the flooding in Mumbai in early July.

My journal picks up again on July 8, a Monday, with the pages of the preceding weekend blank, as if they had disappeared from my life. I noted the absence with dismay.

At that point, I had been moved to a private hospital, and my journal was full of puzzlement about what had happened. After my run, a seizure, but what was that even? At first I posited heat stroke from exercising in extreme weather.

Dr. Rajshekhar Reddy, the head of neurology at the Max Hospital, was in charge of my case. He told me what I had, but only in the most circumspect manner.

"A sub-cranial, space-occupying lesion," he said.

"A what?" My skepticism of that euphemism shouted from the page.

Then, for reasons obscure to me, the following pages are devoted to collective nouns for groups of beasts.

A cauldron of bats (what else, Lord Macbeth?).

An obstinacy of buffalo (of course).

A cackle of hyenas (ha ha).

A conspiracy of lemurs (hee hee).

A crash of rhinoceroses (indeed).

And one I already knew: a murder of crows (kaw kaw).

A prickle of porcupines. I had no idea where I acquired these terms, perhaps from a talkative and literary-minded nurse.

Clearly, I thought, this was my mind showing off, saying, "Hey, I'm still in here, regardless of any alleged 'space-occupying lesion.'"

I found that term annoying: it sounded like a pointless euphemism for a tumor, and I said so to Dr. Reddy, who smiled enigmatically but kindly. "We cannot call it a tumor until we can biopsy it and we find tumor cells."

All I could do at that point was laugh. The whole experience was becoming increasingly amusing. I frequently laughed out loud, however bizarre that might have seemed under the circumstances.

I was still seizing up, or so witnesses would report. The medical team would have to induce a coma to get the seizures under control, and at one point (this is hearsay, but too good not to recount), I was taken for dead by a mortuary crew, who toe-tagged me with the following ID: "Unknown Caucasian male, age 47 and a half."

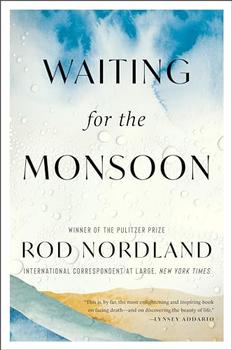

Excerpted from Waiting for the Monsoon by Rod Nordland. Copyright © 2024 by Rod Nordland. Excerpted by permission of Mariner Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

At times, our own light goes out, and is rekindled by a spark from another person.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.