Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

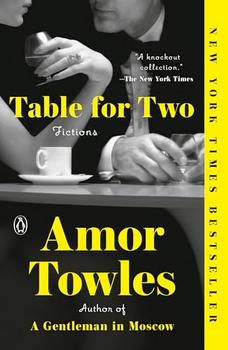

Fictions

by Amor TowlesTHE DIDOMENICO FRAGMENT

Lunch at La Maison

The only advantage to growing old is that one loses one's appetites. After the age of sixty-five one wishes to travel less, eat less, own less. At that point, there is no better way to end one's day than with a few sips of an old Scotch, a few pages of an old novel, and a king size bed without distractions.

Certainly, some of this decline stems from the inevitable degeneration of the physical form. As we age, our senses grow less acute. And since it is through the senses we satisfy our appetites, it is only natural that when our eyes, ears, and fingers falter that we should begin to desire with a diminished intensity. Then there is the matter of seasoned familiarity. By the time our hair goes gray, not only have we sampled most of life's pleasures, we have sampled them in different locations at different times of day. But in the final accounting, I suspect the cessation of appetites is mostly a matter of maturity. Traipsing after a beautiful young thing late into the night, going from one trendy spot to the next and trying rather desperately to think of something witty to say while pouring a well-aged Bordeaux at our own expense... . Really. At this stage, who can be bothered?

But if a decline in the appetites brings some sense of relief to most who age, it is particularly welcome to those in their sixties who can no longer afford the lifestyle of their forties.

On the isle of Manhattan, this population is more sizable than you might expect. Well-meaning husbands, who have put off their financial planning for one decade too many, routinely strand their widows with insufficient funds. Others, who proved capable in commerce as younger men, become careless or even foolish in retirement, wasting badly needed resources on real estate speculations, mistresses, and charity. Then there are those sensible fellows—like me—who, having carefully calculated the necessary capital to support their retirement and prudently set aside savings from year to year, turn a blind eye to the frothiness of a bull market and smugly quit their job only to be brought up short six months later by the ensuing collapse. Whatever the excuses, many who reach their golden years on the Upper East Side find themselves suddenly forced to live below their prior means. So, it's just as well they no longer want what they can't afford.

"Are you finished, Mr. Skinner?"

"Yes. Thank you, Luis."

"Will there be anything else?"

"Just the check."

Clearing what is left of my salade niçoise, Luis winds his way to La Maison's kitchen through a maze of mostly empty tables.

There was a time when you could track the evolution of power in Manhattan by dining at La Maison. Located at 63rd and Madison, offering a serviceable execution of Continental cuisine, the restaurant welcomed real estate developers, advertising executives, financiers, and the ladies who lunched. Over the years, the decor grew a little tired, the food a little outmoded, and those "in the know" moved on to brighter venues serving brighter fare. But if La Maison was no longer the most sought-after table in town, it was not entirely déclassé. There were still a few veterans of commerce and society who, out of habit or lack of imagination, returned for the prix fixe lunch.

There in the corner, for instance, is Lawrence Lightman. A stately six-foot-two, Lawrence hasn't led a publishing house in over a decade, but he continues to wear a coat and tie; and he apparently made enough of a name for himself that aspirants in the field still make the occasional pilgrimage to his table.

Closer to the bar is Bobbie Daniels. A former partner at Morgan Stanley, Bobbie was once considered a prodigy in the field of acquisitions and divestments. In fact, this skill came so naturally to him, he had acquired and divested four different wives. He now has an office at some mahogany paneled trust company where his primary responsibility is the hanging of his hat in sight of the clients.

Excerpted from Table for Two by Amor Towles. Copyright © 2024 by Amor Towles. Excerpted by permission of Viking. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Give me the luxuries of life and I will willingly do without the necessities.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.