Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Discuss | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

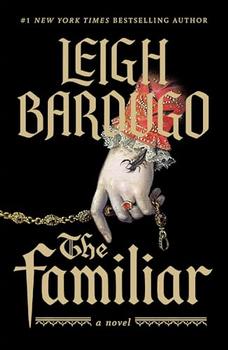

by Leigh Bardugo

When Luzia had seen the burnt bread, she hadn't thought much about passing her hand over it and singing the words her aunt had taught her, "Aboltar cazal, aboltar mazal." A change of scene, a change of fortune. She sang them very softly. They were not quite Spanish, just as Luzia was not quite Spanish. But Doña Valentina would never have her in this house, even in the dark, hot, windowless kitchen, if she detected a whiff of Jew.

Luzia knew that she should be careful, but it was difficult not to do something the easy way when everything else was so hard. She slept every night on the cellar floor, on a roll of rags she'd sewn together, a sack of flour for her pillow. She woke before dawn and went out into the cold alley to relieve herself, then returned and stoked the fire before walking to the Plaza del Arrabal to fetch water from the fountain, where she saw other scullions and washerwomen and wives, said her good mornings, then filled her buckets and balanced them on her shoulders to make the trip back to Calle de Dos Santos. She set the water to boil, picked the bugs out of the millet, and began the day's bread if Águeda hadn't yet seen to it.

It was the cook's job to visit the market, but since her son had fallen in love with that dashing lady playwright, it was Luzia who took the little pouch of money and walked the stalls, trying to find the best price for lamb and heads of garlic and hazelnuts. She was bad at haggling, so sometimes on the way back to Casa Ordoño, if she found herself alone on an empty street, she would give her basket a shake and sing, "Onde iras, amigos toparas"—wherever you go, may you find friends—and where there had been six eggs, there would be a dozen.

When she was still alive, Luzia's mother had warned her that she wanted too much, and she claimed it was because Luzia had been born at the death of the king's third wife. When the queen died her courtiers threw themselves against the palace walls and their wailing was heard throughout the city. One was not supposed to mourn the dead; it was said to deny the miracle of resurrection. But the death of a queen was different. The city was meant to grieve her passing, and her funeral procession was a spectacle rivaled only by her stepson Carlos's death earlier that year. Luzia's first cries as she entered the world were mixed with the weeping of every madrileño for their lost queen. "It confused you," Blanca told her. "You thought they were crying for you, and it has given you too much ambition."

Once, though her aunt had warned against such things, Luzia had tried the same little song of friendship with the coins themselves. The pouch had jangled merrily, but when she reached inside, something bit her. Twelve copper spiders spilled out and skittered away. She'd had to sing over the cheese, the cabbage, and the almonds to make up for the lost money, and Águeda had still called her stupid and useless when she'd seen the meager contents of the shopping basket. That was where ambition got you.

Aunt Hualit had only laughed when Luzia told her. "If a little bit of magic could make us rich, your mother would have died in a palace full of books, and I wouldn't have had to fuck my way to this beautiful house. You're lucky all you got was a spider bite."

Her aunt had taught her the words, pulled from letters written in countries far across the sea, but the tune was always Luzia's. The songs just came into her head, the notes making a pleasant buzz on her tongue—to double the sugar when there was no money for more, to start the fire when the embers had gone cold, to fix the bread when the top had burned so badly. Small ways to avert small disasters, to make the long days of work a little more bearable.

She had no way of knowing that Doña Valentina had already visited the kitchen that morning, or that she had seen the burnt bread in its pan. Because while Luzia had been born with certain talents, far-seeing was not one of them. She wasn't prone to visions or trances. She saw no futures in the patterns of spilled salt. If she had, she would have known to leave the bread untouched, and that it was far better to endure the discomfort of Doña Valentina's anger than the peril of her interest.

Excerpted from The Familiar by Leigh Bardugo. Copyright © 2024 by Leigh Bardugo. Excerpted by permission of Flatiron Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Analyzing humor is like dissecting a frog. Few people are interested and the frog dies of it.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.