Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

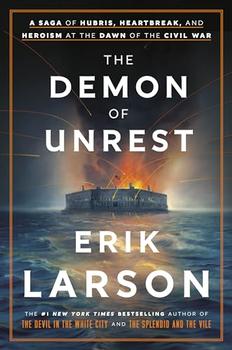

A Saga of Hubris, Heartbreak, and Heroism at the Dawn of the Civil War

by Erik Larson

Anderson was a deeply religious man. To Eba: "I pray that Our Heavenly Father may, ere long, rejoice my old heart by restoring you to health, such that we may be together as long as we live." He summoned the beneficence of God even in formal reports to the War Department. One of his officers wrote, "I never met a man who trusts more quietly and at the same time more contentedly upon the efficacy of prayer." Lately a consistent element of his prayers was a plea that war would not come.

On the stillest nights, at nine o'clock, Major Anderson could hear the great bells in the distant witch-cap spire of St. Michael's Church, bastion of Charleston society where planters displayed rank by purchasing pews. It stood adjacent to Ryan's Slave Mart, and each night rang the "negro curfew" to alert the city's enslaved and free Blacks that they had thirty minutes to return to their quarters, lest the nightly "slave patrol" find them and lock them in the guard house until morning.

Charleston was a central hub in the domestic slave trade, which in the wake of a fifty-year-old federal ban on international trading now thrived and accounted for much of the city's wealth. The "Slave Schedule" of the 1860 U.S. Census listed 440 South Carolina planters who each held one hundred or more enslaved Blacks within a single district, this when the average number owned per slave-holding household nationwide was 10.2. In 1860, the South as a whole had 3.95 million slaves. One South Carolina family, the descendants of Nathaniel Heyward, owned over three thousand, of whom 2,590 resided within the state.

Together these planters constituted a kind of aristocracy and saw themselves as such. They called themselves "the chivalry." As the prominent South Carolina planter James Henry Hammond put it, they were "the nearest to noblemen of any possible in America." This idea was affirmed on a daily basis by the fact of their possession of, and dominion over, a subservient population of enslaved Blacks. But with this also came a deep fear that this population over which they exercised such stern rule might one day rise in rebellion. The 1860 federal census found that the state had 111,000 more enslaved people than it did whites; it was, moreover, one of only two states where this kind of imbalance existed, the other being Mississippi. Free and enslaved Blacks together accounted for over 40 percent of the population of South Carolina's chief city, Charleston, and this caused uneasiness among its white citizens. Planters built what were in effect backyard plantations with two or more out-structures housing kitchens, stables, and slave quarters and surrounded by high walls to limit the dangers of insurrection and midnight murder. Any enslaved person who worked outside these walls had to wear a special badge, a metal medallion—square, round, octagonal—stamped "Charleston," with the year, type of job, and an identification number pinned to clothing or hung around the neck. The effect of this overwhelming slave presence was immediately evident to travelers from the North. "How strange the aspect of this city!" one such visitor observed. "Every street corner, and door-sill filled with blacks; blacks driving the drays & carriages, blacks carrying burdens, blacks tending children & vending articles on the sidewalks; blacks doing all."

Not only did the state's planters call themselves "the chivalry"; they devoured chivalric novels, like Sir Walter Scott's Ivanhoe and Tennyson's Idylls of the King. They held jousting competitions, called "heads and rings," where a rider bearing the name of one of Scott's or Tennyson's knights, wearing knightly garb and holding a long lance, would ride at full gallop and attempt to spear a series of dangling metal rings as small as half an inch in diameter, then draw his saber to take an exuberant swipe at the head of an inanimate figure at the end of the course. The chivalry gave themselves military titles and favored elaborate uniforms. Their South Carolina standard-bearer, novelist William Gilmore Simms, wrote eighty-two novels in which chivalry and honor were central themes. Chivalry, to him, meant "gallantry, stimulated by courage, warmed by enthusiasm, and refined by courtesy." The chivalry valued honor above all human traits and would happily kill to sustain it, but only in accord with the rules set out in the Code Duello, which specified exactly how a man suffering an abrasion of honor could challenge and, if he wished, murder another.

Excerpted from The Demon of Unrest by Erik Larson. Copyright © 2024 by Erik Larson. Excerpted by permission of Crown. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.