Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

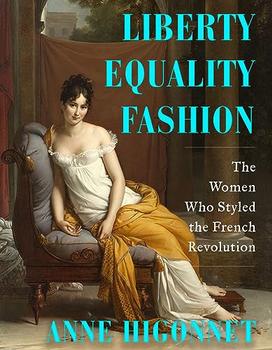

The Women Who Styled the French Revolution

by Anne Higonnet

The Code Noir also governed the clothing of the enslaved. For centuries, sumptuary laws in mainland France had regulated who was allowed to wear what materials, according to a strict hierarchy with the king at the top, aristocrats sternly ranked at the next level, professionals in the middle, and peasants at the bottom. In 1685 an even lower rank was added for France's colonies by the Code Noir. Plantation masters were obliged to provide each enslaved person with two outfits of the coarsest linen or cotton fabric, toile (canvas), or else to provide four aunes (ells, equal to roughly 1.15 yards) of such cloth a year. Four and a half yards of fabric would barely have been enough for two straight, sleeveless shifts that would not reach much past the knees.

In 1685, this one Code Noir sumptuary edict applied to all the enslaved imported from Africa. As the decades passed, however, the racial character of the islands became more complicated, as Joséphine knew from Marion and Euphémie, among other house-servants on her family's plantation. The rape of enslaved women had done its heinous work and inadvertently produced a group in between Black and White. To deal with this demographic development, the French government decreed a dedicated sumptuary edict on June 4, 1720, six years before Joséphine's grandfather settled in Martinique. Like the Code Noir, the 1720 edict allocated the coarsest types of cotton to the enslaved. In addition to a modification of the old category, "negroes, mulattos, and indigenous [Carib] Indians," the 1720 edict inserted a new category: "mulattos and freed or born free [Carib] indians or negroes." Those in this category were allowed cast-off clothes from their masters and household liveries with silver trim, but forbidden any gold, gems, silk, ribbons, or lace.

Only thirty-four years later, another sumptuary edict was pronounced. It expressed mounting White anxieties about how clothing identified race. By 1754 some mixed-race people in the Antilles were very light-skinned, as well as free and skilled. The more racial boundaries blurred, the more urgently White colonists tried to sharpen boundaries with clothing. The 1754 edict divided people of color into three clothing categories: field- or garden-slaves, house-slaves, and mixed-race free people. To each category was assigned a different quality of cotton. Though the edict decreed that free mixed-race people were still not supposed to wear gold, gems, silk, ribbons, or lace, it conceded that they could if the materials were "of little value."

Sumptuary laws were not merely guidelines; penalties for breaking the laws were extreme. A free person could lose their freedom for wearing a forbidden item of clothing; field-slaves were threatened with prison. Joséphine grew up surrounded by the causes and the effects of the 1754 edict. She knew from experience how fearsome sumptuary regulations could be, and also how they could be creatively circumvented.

The 1754 sumptuary edict reflected how women of color had pushed against the limits of the 1720 sumptuary edict. As a child, Joséphine saw, all day every day, the contrast between what the field-slaves on her family's plantation wore and what the house-servants she lived with wore. Women like Marion, who attended her personally on Martinique, and Euphémie, who accompanied her to the mainland, strove against sumptuary restrictions. Differences between cotton textures and colors that to us might be imperceptible, to them were crucial: harsh knee-length sleeveless shifts or sleeved long shifts versus smooth long gathered skirts, blouses, and jackets; cheap "gros guingas" or "grosse indienne" cotton fabric versus the better "Morlaix"; coarse solid off-white fabric versus finer blue-and-white stripes; plain versus two-color-plaid versus three-color-plaid square madras scarves; one-scarf head-wraps versus multiple-scarf head-wraps. Sundays and holidays occasioned the finest that could be obtained. An eminent historian of the French Antilles, Frédéric Régent, has called it "vestimentary bidding."

Excerpted from Liberty Equality Fashion by Anne Higonnet. Copyright © 2024 by Anne Higonnet. Excerpted by permission of W.W. Norton & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.