Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

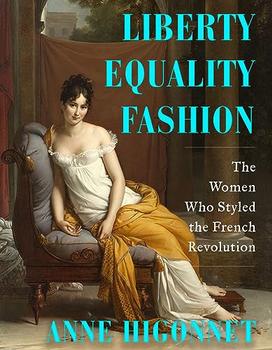

The Women Who Styled the French Revolution

by Anne Higonnet

Anyone who was a lady, however, must have some version of the stiff conical undergarments the shop provided, no matter what materials they were made of. A woman with the slightest pretension to respectability would never dream of meeting guests at home, let alone venturing away from home, without being laced into a corps. The French word corps, which translates into "body," signaled a substitution for the natural body. (The undergarment was called stays in English and in the next century corset.) The corps indeed functioned as a second skin, the surface society imposed on women's torsos.

Despite the tailleur de corps boutique being dedicated to intimate feminine undergarments, its master and underlings were men. Men controlled all the ancient craft guilds, including the powerful clothing guilds. Since 1268, when guild regulations had been codified by the Établissements des métiers de Paris, usually called the Livre des métiers, the guilds had structured the entire skilled labor force of the kingdom, in France as in every European monarchy. The master tailleur de corps felt part of the collective authority of more than a hundred French crafts. In eighteenth-century Paris, he was one of between 30,000 and 40,000 masters, who with their apprentices and journeymen numbered over 100,000, out of a total Parisian population of about 600,000–650,000. Masters enforced strict quality standards, none more stringently than the clothing-guild masters of Paris. So when the master tailleur de corps approached Madame de Renaudin and her niece, of course he showed the respect due from a craftsman to a noble. But he did not feel the slightest doubt about what his expert knowledge and the skill of his workers would produce. He knew exactly how a Paris corps should be made.

First, the new customer must be meticulously measured. A good corps had to fit the torso exactly to discipline it correctly. Rose's body was not ideal, with its long skinny straight shape, but then again, all natural bodies posed challenges to the tailor of a corps. His task was to transform nature into elegant artifice. After the measurements, and some negotiation over the quality of linen fabric, Madame de Renaudin and the fledgling vicomtesse de Beauharnais left the boutique. In a workshop right behind the salesroom, construction of the corps began. A craftsman inserted strips of whale baleen between straight channels of stitches to stiffen it. Tiny holes down the edges of the back were rimmed with sturdy stitches to withstand the pull of laces by a maid, which would perfect the hieratic cone shape. At every step, work was checked to ensure it met the tailleur de corps guild standards, as well as the master's finishing instructions. When the order was complete, it would be delivered by a lowly boy to the Beauharnais residence. Because the Beauharnais women were not such highly ranked customers that their patronage was a favor to the boutique, they would be expected to pay their bill.

Meanwhile, many shopping stops lay ahead. The young bride had never imagined such variety or quality. Nothing in Martinique had prepared her for this. Each guild had perfected its particular product. Together, the clothing guilds constituted a Paris fashion system, reinforced by intermarriages and shared neighborhoods. Just to start at the alphabetical top of the list of crafts: Bootmakers (bottiers) turned leather into sturdy footwear that reached above the ankle. Bootmakers were not to be confused with shoemakers (cordonniers), who plied a significantly different set of skills, turning both leather and fabric into more delicate shoes that covered only the foot. The list went on: braid makers, button makers, cleaners, dressmakers, drapers, dyers, embroiderers, fashion merchants, feather dressers, furriers, gauze makers, girdlers, glovers, hairdressers, hatters, hosiers, haberdashers, leather crafters (not for footwear), linen drapers, mercers, pin and needle makers, perfumers, purse makers, ribbon weavers, secondhand dealers, skinners and furriers, skullcap makers, soap makers, tailors, wig makers. To each of these Madame de Renaudin and the bride in her charge would eventually pay a call. The stakes were highest at the dressmaker's because the choice of silk fabrics was so crucial.

Excerpted from Liberty Equality Fashion by Anne Higonnet. Copyright © 2024 by Anne Higonnet. Excerpted by permission of W.W. Norton & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.