Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

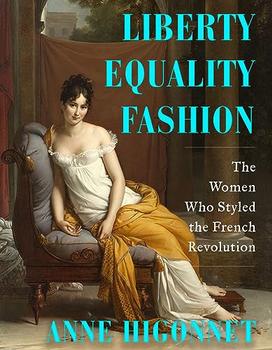

The Women Who Styled the French Revolution

by Anne Higonnet

Rose had no doubt dreamt of French silk before her marriage. The most prestigious gowns in the colony of Martinique were made of French silk brocade. Wearing a silk gown, fitted over your corps, turned you into a lady. All your senses told you so. The silk glowed, its lustrous gleam especially impressive by candlelight. It was so smooth to the touch, yet strong, and your fingers could feel where the flowers were because of the delicate long threads that passed over the background weave. It was hot in the summer months, but then again you had servants to fetch and carry. Perhaps it smelled a bit, because you had worn it for years and it couldn't be washed, only dabbed with cleaning fluids, but those servants laundered your linen chemise so often that the clean chemise smell prevailed. And when food tempted you with its taste, your silk reminded you to eat daintily.

Silk merited investment. Madame de Renaudin sought silks crafted so well that Rose could wear them for the rest of her life, then hand them down to her heiresses. Though styles might change in a decade or two, a gown made with heirloom-quality fabric could be gently altered. Not all silks, however, were created equal. Silks, like French aristocrats, came in a wide range of value. Gold-thread brocades lorded over sprigged floral silks. When the future Joséphine, empress of France, entered the dressmaker's shop in 1779, a guild master would again have rapidly assessed her status, and signaled his subordinates behind another set of wooden counters to unfurl only the silks suitable for a newly minted vicomtesse.

In every boutique she entered, she discovered clothing materials forbidden to her, even after her marriage into the mainland nobility. In Paris, the young Joséphine was confronted with the upper registers of the sumptuary laws whose lowest rungs she had grown up with. No doubt to her dismay, she, who had been at the top of a local hierarchy in Martinique, suddenly realized she was nowhere near the top of the whole French sumptuary system.

Not for a mere vicomtesse the truly splendid silks woven in France's second-biggest city, Lyon. With their shimmering precious-metal-wrapped threads, grand arabesque patterns, and intricate color combinations, those were reserved for the upper echelons of the aristocracy, dominated by pedigreed counts and countesses, dukes and duchesses, princes and princesses. Elite silks included as many as twelve colors and six types of precious-metal thread, along with technically difficult contrasts between smooth and ribbed textures. The skilled women who helped their families weave such imposing silks were unlikely to earn as much in their whole lives as it cost to buy a formal skirt's worth of this most precious fabric.

Nor would a master dressmaker bother to mention to a Madame de Renaudin or a vicomtesse de Beauharnais the most magnificent embroidery his fellow master in the embroidery guild could supply. Such embroidery also used gold or silver thread, sometimes combined with gems and pearls. Ladies at the vicomtesse level could be satisfied with quite marvelously lifelike and textured embroideries in pure silk that would spread their foliage, pistils, stamens, petals, and palmettes across the gowns he was dedicated to assembling.

The master dressmaker would also have astutely modulated his suggestions for how to adorn the gown with passementerie: an untranslatable French word for woven, braided, knotted, twisted, coiled, wired, tasseled, or intertwined trims. It was a waste of his time and perhaps just a bit condescending to mention that one formal court gown alone could require three and a half aunes of trim embroidered with gold and silver thread at 100 livres an aune (an aune was very roughly a yard), three aunes of silver fringe, rhinestones, ribbons, five and a half aunes of ribbon embroidered with spangles, gold tassels, nine and a half aunes of lace, silver fringe and tassels, and three aunes of trim fabric with gold dots. The cost of such finery—just the passementerie, not counting the gown's silk fabric—totaled 1,400 livres, plus 110 livres for the relatively cheap labor: the price of ten gowns appropriate for someone like Rose de Beauharnais.

Excerpted from Liberty Equality Fashion by Anne Higonnet. Copyright © 2024 by Anne Higonnet. Excerpted by permission of W.W. Norton & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Finishing second in the Olympics gets you silver. Finishing second in politics gets you oblivion.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.