Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

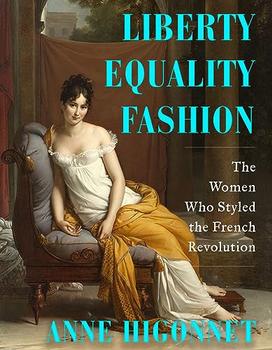

The Women Who Styled the French Revolution

by Anne Higonnet

The master dressmaker might have added a proposal for a moderate quantity of new lace to animate the throat and sleeves of the gown, supposing the two customers did not have their own lace already, perhaps handed down from previous generations. Though lace looked essential to gowns, it was not actually integral to them, being only loosely basted to the silk, so it could be easily removed for gentle laundering. To the consternation of all guild masters, lace was not controlled the way their venerable crafts were. Outstanding lace, microscopically knotted bas-relief linen-thread sculpture, had been produced in France for only a little over a century. King Louis XIV's great finance minister Colbert himself had grown impatient with the hemorrhage of French money to Italy for the best lace. In 1665, he had organized a domestic lace industry under the direct aegis of the Crown. This did not bode well for the authority of the medieval guilds, yet fashion mavens agreed French lace had developed a charmingly ethereal and fluttering flat style of its own.

Madame de Renaudin and the dubious vicomtesse de Beauharnais could only dream of the most magnificent clothing Parisian tailors, dressmakers, embroiderers, and jewelers created: the legendary court habit à la française for men and court robe à la française for women. If they were lucky or clever enough to be admitted into the residences of the sort of nobles who had the birthright to be presented at court, they were likely to see portraits hung on walls to commemorate these outfits of a lifetime. Nobles from every corner of Europe had their Versailles court regalia made by the supreme Paris guilds to ensure maximum éclat. The guilds designed and executed skirts thirty yards around, hung on wicker or metal cages called panniers. It was rumored that some skirts could not fit through the doors of the Versailles palace, obliging the highnesses of Europe to sidle into rooms at angles. Jewels paved the triangular stomacher pieces of their three-part gowns. Waterfalls of lace cascaded from their throats and sleeves, and sometimes swagged across their bodices and skirts.

The Beauharnais and Tascher de La Pagerie families were painfully aware they were not allowed to wear these magnificent costumes. It seemed as if sumptuary laws had governed Europe since time immemorial, because some of them dated back to the fourteenth century. In 1337, the English Crown proclaimed that only the royal family, the highest church officials, earls, barons, knights, and ladies could wear fur. In 1463, English decrees ordered that "no person under the state of a lord" could "wear any manner of cloth or silk being of the color of purple." In 1533 an "Act for the Reformation of Excess in Apparel" reserved crimson, scarlet, and blue silk velvets for dukes, marquises, and earls. A particularly rapid-fire series of edicts were decreed in seventeenth-century France to restrict the use of gold and silver thread: in 1601, 1606, 1613, 1620, 1634, 1665, 1677, and 1680.

Needless to say, families like the Beauharnais and Tascher de La Pagerie clans wanted to cheat as much as they could without getting caught. But by and large, people obeyed sumptuary laws simply because they could not afford to break them. While the members of the aristocracy policed its internal hierarchy with fanatic jealousy, and the range of annual income within that hierarchy was vast, from as low as 10,000 livres to over 100,000 livres, as a class the aristocracy occupied a different order of existence than the rest of the kingdom's subjects. The laboring poor, by far the majority of the population, earned as little as 100 livres a year. Estimates vary, but historians have calculated that between 1 percent and 0.5 percent of France's approximately twenty-three million people in 1789 had noble titles, and only 5 percent of those titles dated back to the feudal era before about 1500. The clerical and secular nobility of France—called the First and Second Estates—paid no taxes, thanks to what were bluntly named "privileges" (though everyone in the Third Estate scrambled for the royal favor of privileged exemption from taxes, sometimes successfully), and controlled the French government, military, and church with absolute authority, an authority encoded in elaborate costumes.

Excerpted from Liberty Equality Fashion by Anne Higonnet. Copyright © 2024 by Anne Higonnet. Excerpted by permission of W.W. Norton & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.