Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

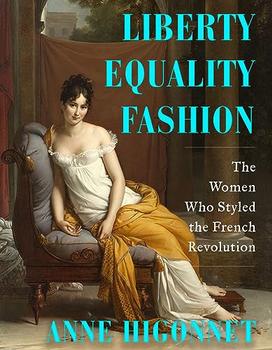

The Women Who Styled the French Revolution

by Anne Higonnet

The bodies of nobles were transformed by their apparel into cosmic apparitions, the bodies of monarchs most splendidly of all. Marie Antoinette, the reigning queen, had a stupendous budget at her disposal. In 1783, she enjoyed an annual clothing allocation of 120,000 livres. In 1785, she spent 258,002 livres, more than twice her budget. Monarchic splendor justified the renewal of Marie Antoinette's wardrobe with thirty-six new outfits every trimester: twelve grands habits, twelve robes à la française, and twelve less formal gowns.

A fairy tale expressed how clothing seemed to perform magic on royal bodies. "Peau d'âne" ("Donkey Skin"), published in 1694 by the great French folklore gatherer Charles Perrault, tells how a king wants his own daughter to marry him. The princess, hoping to avoid his demands, asks that he first give her gowns so impossibly celestial they are like the "blue sky," the "moon," and the "sun." To her dismay, her royal father's craftspeople manage to create the celestial gowns. (But in the end the princess does escape incest.)

When Rose vicomtesse de Beauharnais eventually became Joséphine Bonaparte, empress of France, she did acquire a fairy-tale wardrobe. In 1779, while she was still a sixteen-year-old bride, her Paris shopping trip made her feel that at least she was on her way in that direction. As she looked in the mirror, she could see a fundamental difference between the before of Martinique and the after of Paris. The difference was caused by her new clothes, and by how those clothes changed her body. She discovered that style is not only a formal question of aesthetics, or about how craft transforms materials, or even about how one person can compose the elements of a style most harmoniously or strikingly. Style, she learned by switching from one dress code to another, is also about social power. If ever she took her own status on Martinique for granted, in Paris she learned how clothing gives authority to some people over others.

Every morning, the daily ritual of the toilette taught her body the posture of aristocracy. Over a thin linen chemise, servants tied her petticoats around her waist, for formal occasions topped by a pannier armature. When she was laced into her first Paris corps, she may have felt she could hardly breathe, let alone twist or bend, but she knew she must acquire the calm, dignified bearing befitting her new rank—and her new gowns. After her skirt was lowered onto its base, she had to stand very still while the rigid triangular stomacher was pinned to her corps, lest the sharp pins prick her. More straight pins fastened the bodice, with or without tails and back drapery, to the sides of the stomacher. The bodice was fit on the corps so meticulously that the bodice looked as if it too were a geometric solid. Every tiny piece had been precisely cut and seamed. The three parts of the gown—stomacher, skirt, and bodice—seemed to be one garment, so carefully had they been coordinated.

At last, she appeared as her family hoped. Her attire had turned her into a French aristocrat in the eyes of the world. She had learned just how much a person's sense of self could be changed by their clothing.

Excerpted from Liberty Equality Fashion by Anne Higonnet. Copyright © 2024 by Anne Higonnet. Excerpted by permission of W.W. Norton & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

I always find it more difficult to say the things I mean than the things I don't.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.