Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

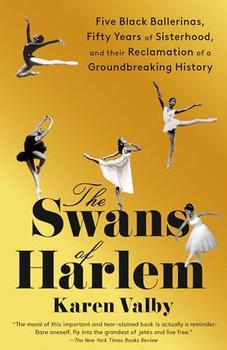

Five Black Ballerinas, Fifty Years of Sisterhood, and Their Reclamation of a Groundbreaking History

by Karen Valby

Mitchell entered the company in 1955, the same year a weary Rosa Parks was told to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus. Some critics reduced a Black man in City Ballet to a "casting novelty" on Balanchine's part. Some said worse. In his debut performance, Mitchell appeared on stage with Balanchine's then-wife Tanaquil Le Clercq in "Western Symphony." At the sight of him, an old white man seated behind the conductor exclaimed, "My god, they've got a n***** in the company!" Commercial television would hold out for years before it aired a performance of Mitchell partnering a white woman, but in 1968, he and Suzanne Farrell danced a pas de deux from Balanchine's "Slaughter on Tenth Avenue" on The Johnny Carson Show. "And in living color, darling!" he cheekily told a reporter afterwards.

Balanchine helped launch Mitchell into stardom by setting his 1957 abstract masterpiece, the central pas de deux in "Agon," on his lone Black danseur and the white Southern ballerina Diana Adams. "My skin color against hers, it became part of the choreography," said Mitchell. His athleticism and technique were put to the highest test in a dance that was as sensual as it was intricate and austere. When a stagehand in the South balked at training the spotlight on a Black man, Balanchine told Mitchell to call upon the reserves of his own internal glow. Fellow City Ballet principal danseur Jacques d'Amboise remembered before his death: "[Mr. Balanchine] said, 'You know, just make light brighter and don't worry.'"

Mitchell turned the lights up in every room he ever entered. On stage and off, the force of his beauty and charisma hit like a wave. The man had key hooks for cheekbones and flashbulbs for teeth. He didn't smile; he shone. He didn't just dance; he set a stage aflame. His herculean work ethic and his preternatural gifts as a performer, coupled with Balanchine's favor, earned him groundbreaking agency over his destiny. He became the first classical Black premier danseur in history, a beloved international star who performed on classical stages around the world, on Broadway, in the movies. Everywhere he went, critics hailed him as the exception to the rule that Black people had no place in ballet. But where some might rest, fat on individual achievement, Mitchell only looked outside of himself, wanting to do more.

In 1968, his career at City Ballet still going strong, Mitchell was under commission to form the National Ballet Company of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro when news of Dr Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination shook him awake, the national trauma igniting within him a sense of spiritual purpose. He knew then that he was needed at home. He decided to build a ballet school in Harlem, the neighborhood that had raised him up. And because children deserve role models who show them what is possible, he would simultaneously establish the first permanent Black professional ballet company.

Art is activism. Let the gorgeous lines of his dancers' bodies serve as fists in the air.

When the school started, in a church basement that doubled as a basketball gym, Lydia Abarca was a teenager living in the projects in Harlem with her parents and six younger siblings. She'd never had a Black dance teacher before. She'd only performed once in her life, as a fourth grader at St. Joseph's Catholic School, to a nun's choreography of "Waltz of the Flowers" from The Nutcracker. But as soon as she descended those basement stairs, Mitchell grabbed hold of her long, elegant feet and swept her into his tornado.

Abarca was a girl who loved to dance, who wanted to be a star, who fantasized about making enough money to buy her devoted parents a house, to move them out of the projects. She wanted to be like her childhood heroes Ginger Rogers and Natalie Wood, emerging from limousines onto red carpets to snapping bulbs, the plot of her life playing out like one of the feel-good "Million Dollar Movies" she loved to watch on her family's black-and-white television. And for a flash of time, a decade of her youth, she had a taste of all that, as Mitchell's muse and Dance Theatre of Harlem's first prima ballerina.

Excerpted from The Swans of Harlem by Karen Valby. Copyright © 2024 by Karen Valby. Excerpted by permission of Pantheon Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Dictators ride to and fro on tigers from which they dare not dismount. And the tigers are getting hungry.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.