Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

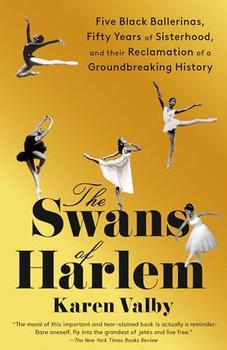

Five Black Ballerinas, Fifty Years of Sisterhood, and Their Reclamation of a Groundbreaking History

by Karen Valby

What they shared was a calling to the classical stage.

It's a rite of passage for so many children, to spend some portion of Saturday dressed in leotard and bunching tights, standing in buckling row of other knock-kneed ducks. A childhood spent twirling in front of a mirror. The future is like a snow globe, where a young girl imagines herself as the star, fairy dust floating down upon her graceful limbs. There is perhaps no more traditional, and traditionally white, feminine ideal than the ballerina—immune to gravity, the embodiment of an aesthetic too pure and fabulous for the grounding of our tedious world. Now imagine a little Black girl twirling in front of her bedroom mirror in a country that has yet to pass the Civil Rights Act or the Voting Rights Act. The innocence and audacity of that child's dream.

Karlya Shelton was seventeen years old when she became the first Black American chosen to represent the United States at the prestigious international Prix de Lausanne competition in Switzerland. "The thing is, I never thought of ballet as a white artform," she says, "because I could do it. So how could it not belong to me too?" These women missed out on meandering childhoods of slumber parties and pep rallies and school dances. They trained in pointe shoes that felt like cement blocks on their feet, practicing until their toes bled. They obsessed over their every line and angle and gesture. And they gave of themselves gratefully. All that discipline, all that grind, undertaken as acts of love. They worked to master their technique so they might experience the ecstasy of breaking free of their self-conscious mind on stage. They quested for perfection while living with the knowledge that a ballerina will dance a flawless performance just a handful of times in her entire career. Says Shelton: "When you get it right, when everything works, there is magic. You become the music and you let it carry you and you ride on it like waves."

McKinney-Griffith describes ballet as her "choice of expression." Before every performance she'd knock three times on the wooden stage for luck, then cross over from the mortal to the divine. "It's like there's an energy curtain," she says of that last steadying breath in the wings, exhaling out the calamity of expectation. "And then you break through it. You almost feel birds flying over your head on stage. It's so powerful because that's when you break free of your stress. No more training. No more pressure. You show your gift."

"Yes, that's exactly it, Gayle!" says Shelton. "This was our gift. This is what we were given. To deny ourselves, or anyone else, of our gift? No, that just wouldn't do. We danced because we loved to dance, and we loved dancing with each other. We felt beautiful on stage together. There was a love between us that was tangible."

Now, years later, when the Legacy Council is able to gather in person, their bodies curve together in a circle. As they speak, they reach for one another's hands or lean to touch shoulders, their proximity bolstering, providing cushion.

"These are my sisters," McKinney-Griffith says. "We first came together at a very special time in our lives. Then we'd all gone off and had our own journeys. And now here we are coming together again in our old age. We're still a nucleus. We're able to tell each other all that we've been through. We laugh, and laughter is healing. And we can cry too, because we've taken all our burdens and thrown them out."

"These were women of great courage," says Tania León, Pulitzer Prize-winning composer and Dance Theatre of Harlem's first musical director. "There was something in them that believed in themselves, and nothing was going to stop them. That is something Arthur had a good eye for—that commitment. I remember when Sheila Rohan danced 'Concerto Barocco' the first time. She was literally crying because her feet were in so much pain."

At eighty-one-years old, a great-grandmother seven times over, Rohan is the oldest of the five women. She was a twenty-eight-year-old mother of three when she first joined the company, keeping quiet about her age and about her children back home so as not to jeopardize her acceptance. "You know how they talk about planting seeds?" she says. "Arthur Mitchell planted a seed in me, and these women helped to nurture that seed and make it grow. It was like a rebirth for me. I felt strong. I felt confident. I started to know myself. Coming from Staten Island, I was a country girl from the projects. My first time on a plane was to go to Europe to dance on stages in theaters that looked like museums. I thanked God every day for the experience. But you put things behind you. You move on. Coming together again, I remember how much it all meant to me. I didn't have to be a star ballerina. It was enough that I was there. I was there. I was there."

Excerpted from The Swans of Harlem by Karen Valby. Copyright © 2024 by Karen Valby. Excerpted by permission of Pantheon Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Censorship, like charity, should begin at home: but unlike charity, it should end there.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.