Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

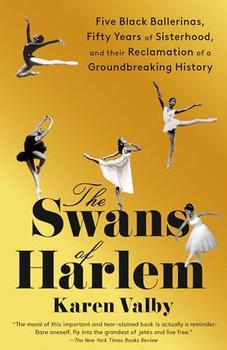

Five Black Ballerinas, Fifty Years of Sisterhood, and Their Reclamation of a Groundbreaking History

by Karen ValbyPrologue

At the height of the Civil Rights Movement, Lydia Abarca was a Black prima ballerina for a major international company, starring in iconic works like Balanchine's "Agon" and "Swan Lake," Jerome Robbins' "Afternoon of a Faun," and William Dollar's "Le Combat." Critics described her as "the dreaming soul of dance," and "a living ode to beauty, incapable of an ugly gesture or a false movement." She was the first Black ballerina ever to grace the cover of Dance magazine. She performed for queens and kings, in the movie production of The Wiz, for Bob Fosse on Broadway. She was one of Revlon's original Charlie's Girl models. An Essence cover star. The object of affection for everyone from Mick Jagger to David Bowie. Roses collected at her feet around the globe.

Half a century later, during Black History Month, Abarca's thirty-two-year-old daughter Daniella wanted to brag about her mother to their friends and family. She went looking for evidence of all Abarca had done—all the barriers she had broken, all the history she had made—but in researching the history of Black ballet, she could only find stories about one young woman, Misty Copeland. Misty Copeland, Misty Copeland, Misty Copeland. The first Black ballerina, insisted the internet. And, indeed, in 2015, Copeland became the first African American woman to be promoted to principal dancer at ABT, breaking the company's seventy-five-year record of whiteness. Thank God for Copeland's talent and her perseverance, for the breaking of poisonous runs. But why, Daniella cried, had her own mother been so thoroughly disappeared in the telling of Copeland's accomplishments?

Just days later, Abarca's only grandchild, Hannah, came home from preschool in the suburbs of Atlanta, her head flooded with stories about the singularity of Misty Copeland. Four girls in her class had chosen the ubiquitous ballerina as the subject of their Famous Black Americans project. Hannah had sat confused on the class rug, listening to how Copeland had been the first to kick down doors so that children like her could live more comfortably in their dreams.

"But what about Grandma," Hannah blurted out at the dinner table that night.

Daniella was furious, unsure where even to direct her anger. "Where's your name?" she cried to her forgotten mother. "Where's your name?"

George Balanchine, long considered the father of American Ballet, and the co-founder and artistic director of New York City Ballet, was famously said to prefer his ballerinas "the color of a peeled apple." (His apologists insist he was only talking about Suzanne Farrell, one of his most iconic muses.) To this day, City Ballet has yet to anoint a Black principal ballerina.

But it was also Balanchine, along with his City Ballet co-founder Lincoln Kirstein, who recognized greatness in Harlem's own Arthur Mitchell and encouraged his rise to become the company's first Black principal dancer. Kirstein had been in the audience for Mitchell's graduation exercise at the School of the Performing Arts, when he performed a solo entitled "Wail," choreographed to Bela Bartok's music. Mitchell had lacked formal dance training when he'd been accepted into the school, relying instead on his exuberant sense of showmanship, auditioning in a rented white top hat and tails with a tap dance routine to Fred Astaire's "Steppin' Out with My Baby," taught to him by a vaudevillian performer he'd looked up in the phone book. Throughout his time there, he withstood pressure from the school's administration, pushing him towards modern dance. "It was better for 'primitive peoples,'" he explained to a People reporter in 1975. "I said to hell with that; I wasn't raised speaking Swahili or doing native dances. Why not classical ballet?"

Upon Mitchell's graduation, Kirstein offered him a scholarship to the School of American Ballet, the preparatory school for the New York City Ballet, telling the young dancer what so many successful Black people know to be true: "Lincoln put it to me with brutal frankness," Mitchell said. "He told me I would have to work twice as hard as anyone in my class."

Excerpted from The Swans of Harlem by Karen Valby. Copyright © 2024 by Karen Valby. Excerpted by permission of Pantheon Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.