Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Despite our wealth, Nai Nai watched the pantry with military precision. Every evening, she weighed the flour to make sure that Mom wasn't being too generous to the workers. The food was never enough, so Mom snuck extra helpings where she could. Through practice, she learned to spin white lies that squeaked under Nai Nai's shrewd radar. Once, Mom made pork buns for a worker's sick child and told Nai Nai the meat was gone because it had spoiled. She passed extra noodles to everyone, and then claimed that mice had broken into the pantry. The workers appreciated Mom and understood the gravity of these risks, because they had a saying: "Wild dogs are dangerous, and ghosts are scary, but nothing is more terrifying than Madame Ang," my Nai Nai.

Nai Nai could have hired servants to help Mom with her tasks, but she considered frugality a pillar in sustaining the Ang fortune. Also, she detested Mom-first, for marrying her son, and second, for having large feet. My parents had been betrothed as infants, and Mom's family, the Daos in Rizhao, were biao cousins of the Angs. Biao cousins had different surnames and, at that time, could marry one another, but tang cousins, who shared the same surname and family tomb, were akin to siblings.

The Daos owned the majority of the ships in Rizhao's waters and prospered through maritime trade. A wealthy girl like Mom should have had properly bound feet, and my Lao Lao had tried to bind them-she had wrapped Mom's feet early on, insisting that a happy husband was worth the agony of broken bones. In Lao Lao's world of silk and porcelain, the freedom to walk was an acceptable price to pay for a man's affection. The Kuomintang, the Nationalist government, however, had banned foot-binding, and their campaigns against it grew increasingly aggressive. After a few years, Lao Lao grudgingly cut Mom's bindings. The damage, however, was irreversible. For the rest of her life Mom hobbled, her feet having been molded flat on the bottom with a pronounced arch at the top.

Nai Nai, meanwhile, had remained defiant before the Nationalist prohibition. She was proud of her three-inch lotuses, and no government lackey could scare her into relinquishing thousands of years of tradition. "Large feet are for peasants," Nai Nai said with disdain when seventeen-year-old Mom arrived for the wedding. "If you aren't a proper lady, you might as well be useful!"

I wished that young Mom had heeded that red flag and fled back to Rizhao, begging her parents for another match. Instead, she went ahead with the ceremony, cutting ties with the Daos-a bride's mother used to throw a bucket of water out the front door after the wedding to symbolize that her daughter, like the water, could never return.

Salivating, Mom told me that her parents sent crates of crabs for that banquet, which ended up being her last special meal. In our shiheyuan, Mom was not allowed to eat crab, because Nai Nai reserved delicacies for the men. Instead, Mom had to crack open the shells and pluck the soft flesh into bowls for Father and Yei Yei. She might have snuck a bite here or there, but it was a great change from her childhood of abundance to her married life, taking a quick morsel while hunched over a counter, with one eye on the door. In her own house, my mother was a thief of minuscule riches, eating these stolen tidbits not only for the taste but for the evocation of childhood memories, the only luxury that she could keep for herself.

On the morning of our eviction, Mom had been in the kitchen poaching eggs for Nai Nai's breakfast. As she filled the sink with water, the smell of dirty dishes triggered a bout of nausea and she vomited. Sirens went off in Nai Nai's head, and she launched her accusations like cannonballs. "You're pregnant, aren't you?" she cried, upending the remainder of her soup, white threads of egg sloshing all over the table. Mom should have lied, but she was too sick to think straight and crumbled under Nai Nai's glare. She nodded.

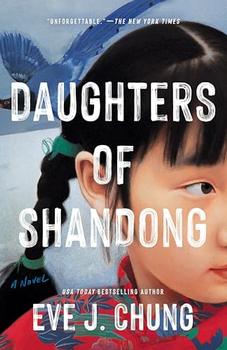

Excerpted from Daughters of Shandong by Eve J. Chung. Copyright © 2024 by Eve J. Chung. Excerpted by permission of Berkley Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.