Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Grabbing Three, I dove underneath the table as Nai Nai began yanking bowls from the cabinets. Angry Nai Nai didn't care about wasting money, which meant she didn't care about anything. Screaming, she hurled the bowls at Mom, who covered her head as they shattered like ceramic bombs against the wall. Sharp shards scattered across the floor as Three shook in my arms-she knew better than to cry when Nai Nai was in a mood. "My son would never disobey me!" Nai Nai shrieked, her aim worsening with her mounting fury. "You must have had an affair. Tell me who it is. Is it one of the workers? Whoever it is, I'll find out!"

Her tirade lasted at least ten minutes and ended with "Whores go to hell!" and the three of us outside without our jackets. As I wrapped my hands around my bare arms, I wondered what Nai Nai would have done if the fortune-teller had said that Mom would never have an heir. Would she have killed her? Sold her? It was hard to say. I'd lived with Nai Nai all my life, and I wanted to believe that there was a limit to her cruelty. However, the old lady continued to surprise me.

From across the koi pond, my cousin Chiao stepped into the courtyard, clutching a toy sword in his sausage fingers. "Auntie! Hi, Auntie!" he yelled, skipping toward us, his round belly bobbing. "Look what Yei Yei brought me! Hai, wanna play bandits and warlords? You have to be the bandit since you don't have a sword."

Before I could reply that bandits had swords too, Mom said, "Chiao, run inside and get some warm clothing for Hai and Three. It's getting colder now that the sun is setting. When you are back, you and Hai can play."

"Okay!" Chiao agreed cheerfully, not bothering to ask why we were stuck outside. Within our shiheyuan, Chiao was in his own bubble of favor, and it did not occur to him that we were being punished. After all, he was the coveted son of Father's younger brother, Jian, and the only grandson in my generation. He got the best of everything-including crab! Nai Nai gave him crisp fried dough for breakfast and slabs of soft braised pork belly for lunch. Yei Yei said only boys got gifts, and he returned from Qingdao with trinkets for Chiao, while Di and I watched, empty-handed. Girls were lucky to be housed. We were lucky to be raised. We were lucky to be fed.

I was jealous of Chiao, but I knew that only men could worship our ancestors at the family tomb; only Chiao could provide for Nai Nai and Yei Yei, and my own parents, in the afterlife. Di and I were taught to pray for Chiao's success, and I did, because Mom's welfare in the spirit realm would depend on him one day. Zhong nan qing nu, an idiom that meant "Value men and belittle women," was embedded in my understanding of our world.

It was almost sunset when Father came home, a leather bag on his shoulder, Mom frantic at the gate. Three and I waited outside as Father went to find Nai Nai and confess his complicity in the betrayal, his wife trailing small in his shadow. Mom said that once upon a time, Father loved her; I was just too young to remember it. Maybe it was true, but I saw my parents as a land animal and a sea animal chained together, forced to remain on the water's edge-each surviving but neither thriving. When they were younger, Father supposedly snuck Mom pork hock stew from the kitchen and brought her flowers from the field. He changed after he went to study literature at university in Qingdao, shortly before the Japanese invasion. To escape the Japanese bombs, we temporarily moved farther north, to Weihaiwei, a former British territory on Shandong's coast, while Father remained in school. His education transformed him into a man who spoke in proverbs and dwelled in the realm of poetry. After the war, he returned to a wife who knew only cooking and farming. Once surrounded by inspirational teachers and like-minded scholars, at home he found himself in a vacuum of silence, which gradually filled with his resentment. Filial piety, however, required him to produce an heir. His misery-and hers-was irrelevant.

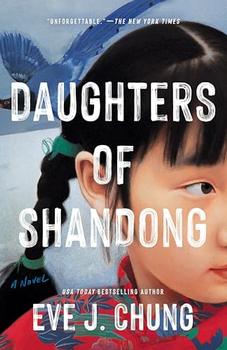

Excerpted from Daughters of Shandong by Eve J. Chung. Copyright © 2024 by Eve J. Chung. Excerpted by permission of Berkley Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.