Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

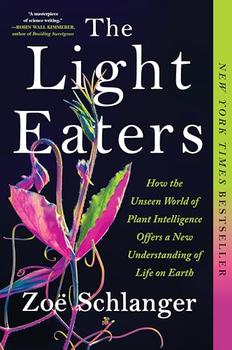

How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth

by Zoë SchlangerPrologue

I am walking along a dim path. Thick hillocks of moss undulate fuzzily around me. I look up, and am dwarfed by pillars of dank and slimy wood. The earth below me is damp, has give. A sign on the path tells me to be alert for aggressive elk in the area. I see no elk, I keep walking. Plumes emerge, sword ferns with their curled fiddleheads the size of a baby's fist covered in velvety auburn hair, the unexpected prequel to the arching fronds that will fountain out above them like peacock feathers. Moss drips in long fingers from branches overhead. Fungi arc skyward from a downed tree. Everything seems to strain upward and downward and outward at once.

I intrude on all this, but no one notices. All things here are so thoroughly absorbed into their own living that I am like an ant slipping discreetly through a sponge. The lichens crawling up the base of trees curl the edges of their disklike bodies up, catching drops as they receive a new day and another chance to grow.

I am in the Hoh Rain Forest in the Pacific Northwest, and everywhere is a sense of secrets. And for good reason. For everything that science does know about what, biologically, is going on here, there is so much more it cannot yet explain. All around me are complex adaptive systems. Each creature is folded into layers of interrelationship with surrounding creatures that cascade from the largest to the smallest scale. The plants with the soil, the soil with its microbes, the microbes with the plants, the plants with the fungi, the fungi with the soil. The plants with the animals that graze on them and pollinate them. The plants with each other. The whole beautiful mess defies categorization.

Thinking about this, I am reminded of the concepts of yang and yin, the philosophy of opposing forces. We know that the forces that shape life are in constant flux. The moth that pollinates the flower of a plant is the same species that devours the plants' leaves when it is still a caterpillar. It is not, then, in the plant's interest to completely destroy the grazing caterpillars that will metamorphose into the very creatures it relies on to spread its pollen. But likewise the plant cannot bear total leaf destruction; without leaves, the plant can't eat light, and it will die. So after a while the besieged plant, having already lost some limbs and therefore showing tremendous restraint, judiciously begins to fill its leaves with unappetizing chemicals. At least most of the caterpillars will have eaten enough to survive, metamorphose, pollinate. Everyone in this situation comes within a hair of death to ultimately flourish. This is the push and pull of interdependence and competition. At the grand scale, no one seems to have yet won. All parties are still here, animals, plants, fungi, bacteria. What we end up with is a sort of balance in constant motion. All of this pushing and pulling and coalescing, as I have come to understand, is a sign of tremendous biological creativity.

How to get our minds around all of that complexity is the shared professional problem of science and philosophy, but also of every person who's stopped to wonder. All that roiling life that won't stand still long enough for us to get a good look. Narrowing our focus to only plants seems at first sensical; that should be easier, being one thing. But that quickly proves naive. Complexity lives at every scale.

Journalists in my line of work tend to be focused on death. Or the harbingers of it: disease, disaster, decline. That is how climate journalists mark time as the earth passes benchmark after grim benchmark on its way into the foreseen crisis. There is only so much of this that one person can take. Or perhaps my tolerance was thin and easily worn out after years of focus on droughts and floods. In recent years I'd begun to feel numb and empty. I needed some of the opposite. What, I wondered, is the opposite of death? Creation, perhaps. A sense of becomings instead of endings. Plants are that, given as they are to continuous growth. They'd soothed me all my life, long before studies came out confirming what we already knew: that time spent among plants can ease the mind better than a long sleep. Living in a dense city, I'd walked in the park under a canopy of yews and elms when I needed to clear my head; I'd spent long minutes gazing at the new leaves forming on my potted philodendrons when my nerves were fried. Plants are the very definition of creative becoming: they are in constant motion, albeit slow motion, probing the air and soil in a relentless quest for a livable future.

Excerpted from The Light Eaters by Zoë Schlanger. Copyright © 2024 by Zoë Schlanger. Excerpted by permission of Harper. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

I like a thin book because it will steady a table...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.