Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

PART ONE

LAUGH NOW CRY LATER

ONE

At Jack's flat, he let you smoke indoors. Hal went out for a fag anyway and saw that the sun had risen; there was warm spring light on him. He walked up the road against a perpetual flow of small children in embroidered jumpers and rounded collars, and got on a bus that would take him northwest across the Thames. The sun was on his right shoulder and his temple was on the window. He struggled to fix his eyes on the back of the man in front of him. His own stink hovered about him: skunky weed, spilled Pimm's and gin, cigarettes smoked in a flat that had had a lot of cigarettes smoked in it before, the vile mix of sweat and deodorant that had congealed under his armpits and was soaking through his pale blue oxford shirt. Sensing he was about to feel very bad, he took his aviators off the neck of his shirt and put them on his face. The bus was passing across Vauxhall Bridge; the sun was in the scummy green water, making it look almost translucent, as if it were more water than filth. Literally the most fucking beautiful thing, he thought. Here I am in London in the twenty-first century, and there's the Thames that was there when the first Duke of Lancaster was born, and there's the long-lived sun.

He got off the bus in Kensington and went into St. Edward the Martyr's just as the Wednesday morning Mass was beginning. He'd avoided Mass since Lent began because his father had been pleading for him to go. Hal liked to have fun, he liked not to suffer. It was just that he had decided when he left Jack's flat that going to Mass would be better than going back in. There was something soothing, after a night of hard drinking, about reciting, "Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world, have mercy on us. Lamb of God ..." Though his throat was sore, Hal's voice was resonant, dominating the dozen others. At twenty-two, he was the youngest there by decades. He'd been avoiding glances so zealously that he hadn't been able to tell whether any of the congregants were people he knew, but he thought they must have been. The back of his neck, and the damp stains on the back of his shirt, had the feeling of being looked at. The interior of the church was cool and airy, the sunlight bright but without heat, floating above the shadows that circled the nave. Still, an overfamiliar line of sweat dripped down the inward curve of his lower back. His mouth was dry, his lips were cracked and aching from being licked.

The priest who led the Mass was the particular confessor of Hal's father.

Father Dyer was an old man and had known Henry since he was young, Hal since he was baptized. He had known Hal's mother. Hal was only third in the queue for Communion; Father Dyer looked him in the eye as he offered him the Body of Christ, which Hal took obediently. He was going to vomit—Oh God, not here ...—oh, no, it had passed, he felt better ... oh, no, there it was again. The vivid light coming through the stained glass in the chancel vibrated at the edges. He slurred, "And with your spirit," when it was asked of him, and timed his exit so that he passed Father Dyer as he was shaking someone else's hand. There he was, one and done, state of grace achieved in forty minutes. St. Augustine had said that drinking to excess was a mortal sin, but as the Church had not established a blood alcohol limit, Hal had decided that he had to confess only if he lost consciousness.

Bordering the south wall, shaded by two old lime trees and several taller, newer buildings, was a small graveyard. It had been opened some years before the Catholic cemeteries in Kensal Green and Leyton; most of the headstones were thin, leaning, illegible remnants. In a spot of sun, there was a small white marble grave marker so brightly new that it seemed unreal, as if there couldn't really be a body underneath. The body belonged to Hal's grandfather's elder brother's only son, whose name was Richard, and who had been born the same year as Hal's father. He had died young, childless. Henry was the one who had buried Richard here. The previous dukes were interred side by side in St. Michael's and All Souls in Lancaster, with the exception of the sixth duke, who had died of mysterious causes while imprisoned in the Tower of London. Hal felt he should pay his respects. If Richard hadn't been such a degenerate, Hal's father wouldn't care nearly so much that Hal was too. It was like Oscar Wilde had said: to have one queer in the line of succession was a tragedy, to have two looked like there was something fucking wrong with your family. And, in fact, the Lancasters had had three: Hal's great-great-grandfather had died in exile after going wrong with a Frenchman. Now Hal was son and heir, possessing nothing but a subsidiary title, an unignorable sense of his own preeminence, and a daily terror of this preeminence going unnoticed by everyone in the world except his father, who had rung him nine times back-to-back while he was at Mass.

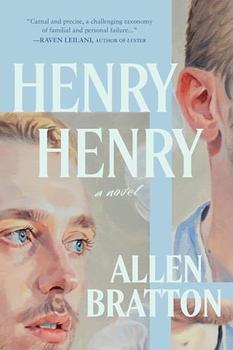

Excerpted from Henry Henry by Allen Bratton. Copyright © 2024 by Allen Bratton. Excerpted by permission of The Unnamed Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.