Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

In addition to doing the laundry, which overfilled the hampers and slumped like dead birds on every surface, I mopped the floors, vacuumed the rooms, and cleaned the patient and employee bathrooms. I refilled the soap dispenser in the patient bathroom, which dribbled like a nosebleed, its residue jellying on the rim of the sink. Every hour, I sponged away the gum. The toilet bowl turned brown because of mineral buildup, and although I scrubbed it daily, it always looked like someone had recently stewed their shit in it. The toilet-paper dispenser was broken and had to be bandaged with Scotch tape.

When I stirred the brush inside the bowl, I heard the contents of my own bladder sloshing, slapping all the walls of my body. I became aware that I needed to use the bathroom, but I abstained. I liked to see how long I could wait. My bladder stiffened into bone and became my fist. It tautened into a grape of pain.

The chiropractor claimed that at his busiest, he saw over one hundred patients a day, and though I never knew if this was true, never saw anyone coming or going, I gathered the aftermath of their bodies: alcohol-soggy cotton balls sunken in the trash cans, paper towels souping in the sink, handprints of sweat gilding the tables, bouquets of dark hair arranged in the chamber of my vacuum cleaner. Though the job was full time, the chiropractor said he'd only take me on as an independent contractor, which I knew was just a way of saying I'd have no benefits. My brother told me those were the best kinds of jobs: make sure they pay in cash, he said, you won't have to pay taxes. He collected bills from handyman gigs and rolled them into sausages, encasing them in socks that were sweat-encrusted and mildewed—a natural repellent against thieves. In my family, we weaponized our stench.

It was Wednesday when I saw Cecilia. Unlike the receptionist, who had to keep track of appointment dates, I never knew the day of the week or whether it was winter, though it was winter. In the windowless room, it was always warm, and the wet fluorescent light flicked my earlobes with its tongue. At work, all conscious thought was caught in the mesh screen of my mind and balled away, and what remained was the beeping of the machine when it was done or overloaded, my fingers groping for corners, the volcanic power of the chiropractor's piss as it plundered the pipes and grew gold roots beneath my feet. My only aspiration was to expel myself that fluently. On his best days, there was no trickling or tapering off: it ended as abruptly as it began, the stream severed cleanly as if it were snipped.

I learned it was Wednesday because the chiropractor, after exiting the bathroom that morning, turned to me and said, A lot of new patients today, and on a Wednesday. He said nothing else, and the words caught in my mind's screen, separate from my living. Inside this room I was ghostly, a fly's wing, leashed to the light above me. I folded to the rhythm of on a Wednesday, pluralizing each pleat, manufacturing halves and then quarters, rolling and stacking, bending and filling.

The receptionist knocked twice, Get the room, so I abandoned the hand towel I was using to wipe the window of the washer, leaving it to puddle on top of the machine.

The treatment rooms lined a narrow carpeted hallway, rows of sliding doors on either side. Unless you dislocated the doors a little, jiggling them in their sockets, they didn't slide shut properly, or they made a metallic scraping sound that turned your spine to slime. When the doors were left half open, it was a sign for me to enter and clean the room as quickly as possible, without jostling the requisite plastic spine model. Each vertebra was labeled with a number, the spaces between them glowing like keyholes, inviting any finger to try and unlock them. As much as possible, I liked to face the spine while I cleaned; if I didn't keep an eye on it, I heard the bones jingling like forks. They pricked my skin, took bites of my mind.

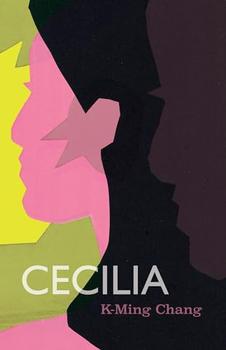

Excerpted from Cecilia by K-Ming Chang. Copyright © 2024 by K-Ming Chang. Excerpted by permission of Coffee House Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.