Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

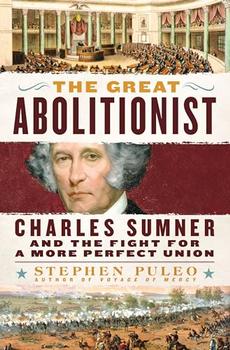

Charles Sumner and the Fight for a More Perfect Union

by Stephen PuleoCHAPTER 1 "WE ARE BECOMING ABOLITIONISTS … FAST"

Charles Sumner was saddened, though not overly sympathetic, when he saw his first slaves in 1834 at the age of twenty-three.

Fresh out of Harvard Law School, Sumner left Boston by stagecoach at 3:30 A.M. on February 17 for his first trip to Washington, D.C. His mentors, Harvard dean and associate Supreme Court justice Joseph Story and Professor Simon Greenleaf, had suggested the trip to the nation's capital, believing that for Sumner to excel at the law, he had to understand the way the country's politics worked and gain a broad acquaintance with judges and government leaders. Sumner also welcomed the trip as an opportunity to spread his wings after years of painstaking classroom study and cloying and overbearing supervision from his demanding father.

The long journey, portions of which were made by steamboat and railway (Sumner's first train ride), was tiring but exhilarating.

Departure night was so dark that Sumner, riding up front with the driver while eleven other passengers sat in the coach, did not realize until the break of dawn, ten miles from the city, that the wagon was pulled by six sturdy horses, a number Sumner marveled at in a letter to his family. Later, Sumner was the sole passenger on a "gig"—a small carriage pulled by a single horse—again riding alongside the driver "over roads nearly impassable to the best animals," while enduring "benumbing" cold. As the driver wrestled to keep the carriage on course, Sumner—at the driver's request—rained blows from his whip upon the horse to move the reluctant animal along, "literally working my passage … my shoulder was lame for its excessive exercise in whipping the poor brute." Changing horses every sixteen miles, the gig arrived in Hartford near 2:00 A.M. the next day, twenty-three hours after Sumner left Boston. Another stagecoach brought Sumner to New Haven, from which he boarded a steamer to New York City.

New York's "perpetual whirl and bustle" thrilled him. "I am now in the great Babel," he wrote to his parents, a young man on his own in the big city. "The streets flow with throngs, as thick and pressing as those of Boston on a gala day. Carriages of all sorts are hurrying by … omnibuses and Broadway coaches … are perpetually in sight.… One must be wide awake, or be run over by some of the crowd." Sumner then traveled by boat to Amboy, New Jersey, where he took his first train ride for nearly forty miles, "part of the way going at the rate of more than twenty miles an hour!" From there, he was on to Philadelphia and Baltimore by a combination of stage, railroad, and steamboat.

By the final leg of his exhausting six-day journey south, on a stagecoach ride from Baltimore to Washington—a stretch of only thirty-eight miles through "barren and cheerless country" that took all day over the "worst roads" Sumner had ridden upon—Sumner spotted a group of slaves toiling in a field. He appeared to view them with a combination of contempt and curiosity.

"My worst preconception of their appearance and ignorance did not fall as low as their actual stupidity," he wrote to his parents. "They appear to be nothing more than moving masses of flesh, unendowed with any thing of intelligence above the brutes." He concluded his reference with an ambiguous aside that may have been an indictment upon the South itself, the slave system, or the jarring sight of seeing enslaved people: "I have now an idea of the blight upon that part of the country in which they live."

He made no other direct reference to slavery, either in that letter or any others he wrote from Washington, D.C., in 1834.

* * *

Upon reaching Washington, Sumner immersed himself in the city's political scene.

He settled into a routine wherein he rose at seven o'clock each morning, and after breakfast, visited a congressman or two. By late morning, he was in the Capitol building—a structure "that would look proud amidst any European palaces"—where he attended congressional debates or sat in on sessions of the Supreme Court, which met in a dark room on the lower floor, until late in the afternoon. In the evening, he often spent time with Justice Story and his legal associates and friends, dining at "well-furnished tables of the richest hotels," excited that at these lively and invigorating sessions "no conversation is forbidden … the world and all its things are talked of."

Excerpted from The Great Abolitionist by Stephen Puleo. Copyright © 2024 by Stephen Puleo. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Griffin. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.