Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

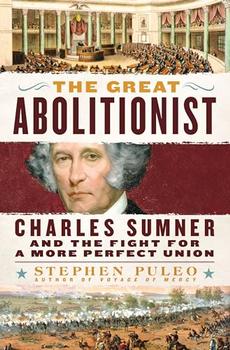

Charles Sumner and the Fight for a More Perfect Union

by Stephen Puleo

Sumner received a hands-on education about the legislative process and speechmaking. He sat rapt as Senator Henry Clay delivered a "splendid and thrilling" oration criticizing President Andrew Jackson, "without notes or papers of any kind … he showed feeling, to which, of course, his audience responded." South Carolina's John C. Calhoun employed his trademark "rugged language" to make an impression on his audience. Massachusetts senator Daniel Webster introduced Sumner to other senators and presented Sumner with his card, "which gives me access at all times to the floor." He watched attorney Francis Scott Key, author of "The Star-Spangled Banner," argue a case before the Supreme Court. He saw the original Declaration of Independence, which hung in the Patent Office, and "paid a pilgrimage to Mount Vernon on horseback."

Sumner described Washington as a "city of magnificent distances," and he walked for miles to take it all in, along the National Mall, up and down bustling and dust-choked Pennsylvania Avenue and the city's other main thoroughfares—and amid the numerous slave pens and auction sites that dotted the heart of the nation's capital.

* * *

In fact, Washington at the time of Sumner's first visit was the nexus for a great slave migration—a slave "trail of tears," as it were—in which hundreds of thousands, perhaps up to one million, "Upper South" slaves, who worked in tobacco fields and as household servants in Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, and Kentucky, were sold to labor-hungry plantation owners in the rapidly growing Deep South cotton and sugarcane states of Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and Louisiana.

Between 1833 and 1836 alone, more than 150,000 Upper South slaves either walked overland for hundreds of miles—usually chained together—to Lower South owners or were transported by ship down the Eastern Seaboard, around Florida, and into the gulf ports of Mobile, Alabama, or New Orleans, where they awaited purchase and another trek to expanding plantations and farms across the Deep South. In Washington, D.C., slave pens were conspicuous in the heart of the city. Large D.C. slave brokers even purchased their own ships to support the coastal slave trade. "The District of Columbia is the great mart for the sale of men," said one antislavery activist in 1834, home to a "vast and diabolical slave trade."

For slave owners, Washington, D.C., was the perfect location through which to transport slaves to the Deep South. Its proximity to the slave states of Virginia and Maryland gave the city ready access to thousands of slaves—and free blacks who were often illegally rounded up and sold into slavery—as well as to the Potomac River and the Atlantic coast. Moreover, slavery proponents knew that if they kept the institution of slavery visible in the nation's capital, it would serve as a vivid symbol of their hold on the nation and the national government.

For antislavery advocates, abolitionists, and foreign guests, the city's slave auctions and pens had the opposite effect. Most expressed disgust at the site of chained slaves trudging past the White House and Capitol. Most turned away with shame as slaves awaited sale and relocation in crowded pens near and on the National Mall, as children were torn from their parents and families were broken apart.

All of the trading activity in Washington, D.C.—chained slaves forced under guard to pens near the National Mall; auctioneers offering men and women for sale as crowd members shouted their bids; newspaper advertisements that connected buyers and sellers of slaves—would have been impossible for Charles Sumner to miss.

Yet, strangely enough, Sumner—a prolific and descriptive writer who penned numerous letters home about virtually every aspect of his Washington trip—never explicitly articulated his feelings about the presence of such slave activity in the nation's capital.

* * *

But he alluded to the issue, especially later in his trip.

Excerpted from The Great Abolitionist by Stephen Puleo. Copyright © 2024 by Stephen Puleo. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Griffin. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.