Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

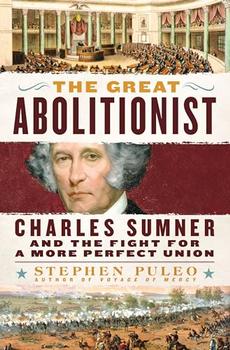

Charles Sumner and the Fight for a More Perfect Union

by Stephen Puleo

"Signs of the deep distress of the country are received every day and proclaimed in both Houses," he wrote to his friend Professor Greenleaf on March 3. And again to Greenleaf on March 18: "The country is in a sad condition, without a discernible sign of relief. I cannot but have a sense or feeling that things cannot continue in this pass … the very extremity of our distress shows the day of redemption to be near. " A few days later, Sumner confided to his father that, while one part of him felt "a little melancholy at leaving," he was ready to come home. "I feel in an unnatural state [in Washington]," he said.

Sumner attributed some of his sadness at the situation in D.C. to a growing dislike for politics as the days went along. His initial ebullience waned, and his letters became more cynical as he watched the political process at work, admitting to Greenleaf that he had felt "no envy" for the fame politicians acquired and "no disposition to enter into the unweeded garden in which they are laboring, even if its gates were wide open to me." To his father, Sumner acknowledged that the more he saw of Washington, the more he was convinced that "I shall probably never come here again. I have little desire ever to … in any capacity. Nothing I have seen of politics has made me look upon it with any feeling other than loathing."

It is hard to imagine that Charles Sumner's disgust for D.C. politics was separate from his feelings on slavery or the signs of slavery that surrounded him in the nation's capital, especially since, upon his return to Boston, the twenty-four-year-old Sumner began taking a deeper interest in the subject.

Sumner's father, Charles Pinckney Sumner, had strong antislavery sentiments, and though Charles and his father were not close, the elder Sumner's convictions carried great sway over his son's thinking. Young Charles denounced proslavery violence in the South, and he began reading William Lloyd Garrison's abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator. He also read abolitionist Lydia Maria Child's An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans, first published in 1833, which further convinced him of the injustice of slavery and racial discrimination in the wake of his Washington trip.

Sumner was far from an antislavery champion in his mid-twenties, but there is little doubt that his first exposure to slavery stayed with him and had an important effect on his early thinking and throughout his life; his thoughts on the injustice of slavery pepper his early letters and other writings.

In January 1836, Sumner wrote a letter to his friend Dr. Francis Lieber, whom he met on his Washington trip and who was now a professor of political economy in South Carolina—in essence, an antislavery sympathizer in the heart of slave country. Lieber had as much influence over Sumner's early thinking on slavery as anyone. Sumner shared his sentiments on the evils of slavery and also felt compelled to tell his friend:

"We are becoming abolitionists in the North fast."

* * *

Not fast enough, apparently, for Europeans, who watched America's ongoing slavery debate with contempt.

And they let Charles Sumner know about it on his first trip to Europe in the late 1830s, a pilgrimage that accelerated his antislavery education and hardened his beliefs.

After his return from Washington, Sumner practiced law and taught at Harvard Law School, but he decided to interrupt both endeavors in 1837 to embark on a long European trip and "visit those scenes memorable in literature and history, and to see … the great men that are already on stage." The desire to cross the Atlantic had burned in Sumner "since the earlier days of memory"; such a trip would allow him to obtain knowledge of "languages … manners, customs, and institutions of other people than my own." Against the advice of his father, Justice Story, and other friends who believed Sumner would damage his career path by embarking on a whimsical journey, Sumner departed on December 8, 1837, aboard the Albany. "I tremble with hope, anticipation, and anxiety," he wrote as he was about to begin his European tour.

Excerpted from The Great Abolitionist by Stephen Puleo. Copyright © 2024 by Stephen Puleo. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Griffin. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.