Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

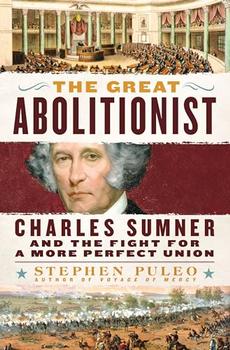

Charles Sumner and the Fight for a More Perfect Union

by Stephen Puleo

After overcoming seasickness that confined him to his cabin for a week on the early part of the voyage, Sumner recovered, relaxed, walked the decks, and engaged with other passengers. By the time the captain spied land on Christmas night, Sumner's spirits were high, and he could not wait to go ashore. "The life of life seems to have burst upon me," he wrote joyfully to a friend.

And indeed, Sumner did enjoy his visits to museums, palaces, libraries, drawing rooms, and cathedrals. But more memorable for him was that, for more than two years, from Paris to London to Rome to Munich to Vienna, Europeans told him repeatedly that American slavery was a disgrace unbefitting a civilized nation. People whom Sumner admired had strong abolitionist opinions and were not shy about expressing them. In London, the Duchess of Sutherland was unsurpassed among English nobility in using her position to argue against American slavery. And in Paris, Sumner met lecturer and author Jean Charles Léonard de Sismondi, whom he described as a "thorough abolitionist" who was "astonished that our country will not take a lesson from the ample page of the past and eradicate slavery, as has been done in the civilized parts of Europe."

But what gave him pause—even more than the opinions of the political, social, and academic elites in his host countries—were the things Sumner saw with his own eyes.

On a freezing January day in Paris ("My hair is so cold that I hesitate to touch it with my hand," Sumner wrote), he attended a lecture at the Sorbonne and spotted "two or three blacks" in the audience. Sumner was surprised that they had the "easy, jaunty air of men of fashion, who were well received by their fellow students," and even more surprised that while they were standing amid their classmates, "their color seemed to be no objection" to the group. Sumner was "glad to see this" but acknowledged that such a scenario would be unlikely in America.

It was at that moment, in France in 1838 at the age of twenty-seven—reinforced by similar scenes in Italy—that Sumner recognized the full import of what he was witnessing and reached the conclusion that would anchor his antislavery and equal rights philosophy.

In his opinion, the camaraderie displayed between students of different races at the Sorbonne could only mean one thing—"that the distance between free blacks and whites among us is derived from education, and does not exist in the nature of things. "

For the remainder of his life, in personal letters and speeches and congressional debates, Sumner would reiterate, in some form, this profound observation and link it to his assertion that the promises of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution applied to all people equally.

By the time he returned from Europe on Sunday, May 3, 1840, Charles Sumner was convinced that American society also would be far better if slavery were abolished.

* * *

How to accomplish that was another matter.

Sumner sympathized with the moral purpose of abolitionists, and even initially gave merit to William Lloyd Garrison's calls to "dissolve the Union" if it could not abolish slavery. But as Sumner thought and read more about the issue, he found distasteful and counterproductive the position of Garrison and his acolytes that the Constitution was a proslavery instrument, "a covenant with death, and an agreement with Hell."

Sumner not only disagreed with Garrison's conclusions about the Constitution, but he also believed such language only served to array conservatives, moderates, and the country in general against the antislavery movement, even as these groups were all potential allies essential to its success. Sumner grew increasingly uncomfortable with the tone of the language used in the Liberator. "It has seemed to me often vindictive, bitter, and unchristian," he said. "I have been openly opposed to [its] doctrines on the Union and the Constitution."

Excerpted from The Great Abolitionist by Stephen Puleo. Copyright © 2024 by Stephen Puleo. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Griffin. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.