Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi

by Wright Thompson1

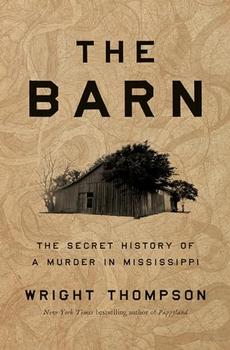

The Barn

Willie Reed awoke early Sunday morning to the sound of mockingbirds. Mosquitoes hovered and darted on the bayou behind his house. The cypress floorboards creaked beneath his feet. He stepped outside into a visible wall of humidity. Local kids like Willie had a name for the little riffles rising from the dirt: heat monkeys, animated like a living thing. A Mississippi Delta sunrise is feral and predatory; even at 6:00 a.m., the air feels hot on the way in and stagnant on the way out. Daylight had broken an hour before Reed started his short walk to Patterson's country store, one of the many little places out in the country that sold rag bologna and hoop cheese. It was August 28, 1955. His grandfather wanted fresh meat to cook for breakfast. He was eighteen years old, with a boyish face that made him look at least three or four years younger, with almond-shaped eyes and delicate lashes. His girlfriend, Ella Mae, lived a few miles south on Roy Clark's plantation. Late August meant they were a week into cotton-picking season. In a few hours, after church ended, hundreds of men, women, and children would be pulling nine-foot sacks through the rows of cotton on the other side of the road. The past few growing seasons had been hard on everyone but for the first time in two or three years the price looked good enough for farmers to clear a little profit, depending on the whim of the landlord. Reed and his family worked for Clint Shurden, one of eighteen siblings who'd all left sharecropping behind to form a little empire around the Delta town of Drew. The Reeds usually made money for a year of work, and Clint also paid Willie three dollars a day to help him out around the place.

The people across the narrow dirt road never made a dime working for their landlord, Leslie Milam, who'd moved into the old Kimbriel place a few years back. Milam was the first member of his hardscrabble family to gain a toehold in the fading, cloistered world of Delta landowners. Bald like his brother J.W., with sagging jowls and a double chin, Leslie was renting to own from the kind of family his had aspired for generations to become, the Ivy League-educated Sturdivants, whose empire included at least twelve thousand acres and a sizable investment in a three-year-old business named Holiday Inn. Leslie's thick brows rose in a perpetual look of surprise above his eyes, which were just a little too close together.

The Black folks who lived in the country between Ruleville and Drew had quickly come to hate Leslie. They had a word for men like him, a whispered sarcastic curse: striver. Leslie Milam was a striver. Just last year he'd told Alonzo and Amanda Bradley that they owed him eleven dollars, which he'd forgive if they stayed another season. They'd also learned to recognize the mean, cigar-chewing J. W. Milam, who came around from time to time.

When old Dr. Kimbriel had farmed the place, the local sharecropper kids like Willie's uncle James would play in the long, narrow cypress barn just off from the white gabled house. Willie had been inside it once, too. The neighborhood children liked to chase the pigeons, which would fly to safety in the cobwebbed eaves. Nobody chased pigeons once Leslie moved in.

That morning Willie turned left on the dirt road mirroring Dougherty Bayou, lined by knobby bald cypress trees. Five million years ago the range of these trees had stretched far to the north of Mississippi, but the Ice Age had reduced them to a narrow band around the Gulf of Mexico. Cypresses, sequoias, and redwoods are some of the oldest trees on the planet, their presence marking a connection to primordial history. Reed walked past the trees, down to the New Hope Missionary Baptist Church, which sat between the road and the bayou.

Dougherty Bayou was the name of the water that drained this part of the Delta into the Sunflower River. Mostly the bayou was known locally for its connection to the Confederate cavalry general Nathan Bedford Forrest, whose postwar extracurriculars included a turn as the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, which had originally been led by his former staff officers. The old white folks loved to talk about the Wizard of the Saddle, about how he led his cavalry along the Dougherty Bayou as he moved quietly toward Yazoo City. Forrest Trail, they called the old Indian hunting path that would become the Drew-Cleveland Road, which would later be renamed the Drew-Ruleville Road, which had originally been built in the first place by Forrest's brother. A cavalry once moved down this road to the beat of horse hooves and animal breath. Reed walked the same ground with the quiet shuffle of shoe soles on dirt. The sun had been up for an hour already, enough early light to bring definition to the rows.

Excerpted from The Barn by Wright Thompson. Copyright © 2024 by Wright Thompson. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Harvard is the storehouse of knowledge because the freshmen bring so much in and the graduates take so little out.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.