Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

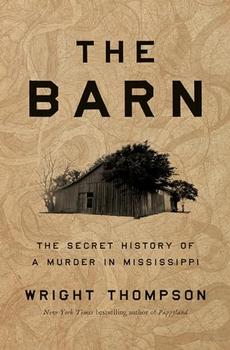

The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi

by Wright Thompson

Abandoned shacks dotted the countryside around Reed's home. There weren't as many people around as there had been just a few years before. Many of his neighbors had already left the Mississippi Delta. These were the last days of a way of life. With each passing year more and more sharecropper houses sat empty as machines replaced people. Modern civilization spun just a few hours north, connected by family ties and railroads and telephones but separated by what Black expats in Chicago called the Cotton Curtain. Local high schools would soon start scheduling reunions in Chicago, since that's where all the graduates were living.

Reed took a left to cut through Leslie Milam's farm, aiming to cross over the dark, slow-moving Dougherty Bayou, full of crappie and bream the perfect size for a cast-iron skillet. That's when he heard the pickup truck. He turned and looked down the road and saw a two-tone Chevrolet kicking up dirt. A white cab with a green body. The truck turned directly in front of him. The driver pulled up to the long cypress barn. Four white men sat shoulder to shoulder in the cab. In the back, three Black men sat with a terrified Black child.

The child was fourteen-year-old Emmett Till. He had two terrible hours left to live.

I first heard about the barn four years ago. An activist named Patrick Weems said we needed to take a drive through the Mississippi Delta during one of those endless days of the early pandemic. I'd been driving a lot during lockdown. My response to the world ending was to go home. I am from Clarksdale, Mississippi, one of those faded Delta farm towns built to support the sharecropper South that emerged in the decades after the Civil War. My family farms the same land we farmed in 1913, just twenty-three miles northwest of the barn Weems insisted I travel to see. I'd been almost completely separated from the agricultural part of my history as a child. My family's farm had seemed like a past I wanted to leave behind. Then being back home in the stillness of the pandemic forced me to consider where and how I'd grown up. What I found as I drove was that all that running hadn't really taken me anywhere at all. I remained a child of the Delta. I'd stop on the levee, a bandanna tight around my mouth and nose to keep out the trailing wake of dust, looking out at the land of my birth. I'd let the red dirt settle and I'd stare out at the endless, flat farms. This was some of the most fertile ground in the world-an alluvial plain and not an actual river delta-made rich by the nutrients deposited by a million years of flooding rivers. If you could fly into the air like one of the extinct songbirds that once called this land home, you could see fingers of water stretching out like a hand from the wide, violent Mississippi into the flatland, rivers like the Yazoo, Sunflower, and Tallahatchie, bayous like Dougherty and Hushpuckena and the Bogue Phalia. Black citizens called the Tallahatchie the Singing River because of all the lynching victims who'd been thrown into its dark water. Their souls sang out from the water, the wellspring of Black death and white wealth.

Farming at its essence is just the practice of getting water onto land and then getting it off again, and the eighteen-county teardrop of the Mississippi Delta did this as well as anywhere on earth. On the eastern boundary between the Hills and the flatland a series of reservoirs trapped the runoff water, and on the western edge levees kept the big river from flooding out crops and people. Humans had stopped the natural order of things, halting the patterns that created their fertile home, working with puritanical resolve to strip out the bounty that had taken a million years to create. Nothing about the physical appearance or ecosystem of the Delta carried any of the Creator's fingerprints. This land is man-made. Never once until learning about the barn had I considered the idea that removing God's dominion from his creation might also remove his protection, his grace, and his oversight, leaving this corner of the world undefended from the impulses and desires of man.

Excerpted from The Barn by Wright Thompson. Copyright © 2024 by Wright Thompson. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

There are two kinds of people in the world: those who divide the world into two kinds of people, and those who don'...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.