Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

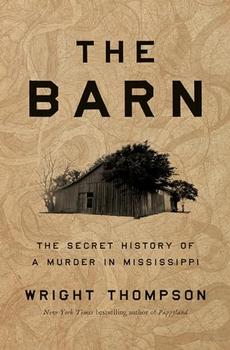

The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi

by Wright Thompson

When I was growing up, the seasons still dominated life. Little towns came alive with planting and harvest festivals. The romantic smell of my childhood world is that sweet, decaying blanket of defoliant that settles on my hometown in the last days of summer. Little yellow airplanes streak across the sky with billowing clouds of poison spraying from nozzles underneath the wings. My mother walks into our front yard when picking season begins and breathes deeply. She's a child again and her father is coming home for dinner, the big midday meal, hanging his fedora by the front door and talking with pride about his stand of cotton. The house is alive with the shuffle of cards and the pop of grease and the understated Methodist prayers for themselves and their neighbors. Her dad got his ship shot out from beneath him in the Pacific Ocean and every morning when he drank his glass of cold milk he quietly went back to the rattling thirst he felt holding on to a piece of decking and looking into the blinding horizon for help. Every Sunday he'd take his family for a drive around the farm, steering his station wagon through the fields, proud about the lack of weeds around his cotton plants. My grandmother and mother loved to make fun of his meticulousness. He'd been a dentist before the war, and they joked that Doc McKenzie wanted more than anything to floss his rows.

I can draw from memory a detailed road map of the Delta. At Tutwiler, Highway 49 forks, the west route going near where Willie Reed walked in 1955 and the east route cutting down to Greenwood, where Reed was born. Highway 1 follows the river, through Gunnison, and runs parallel to Highway 61. Highway 61, where Bob Dylan sang about God wanting his killing done, connects Clarksdale and Cleveland. Little dying farm communities cling to the roadside between the two old railroad towns. Shelby, home of my family, where my grandparents are buried on the outskirts of town. Winstonville, where Ray Charles and B. B. King played to sharecropper crowds at the Harlem Inn, which fire took down to a grassy spot on the east side of the road. Mound Bayou, the famous all-Black town founded by freed enslaved people. And Merigold, ten miles west of the land Willie Reed and his family farmed. All of these places, and the history buried around them, aren't disparate dots on a map but part of a tapestry, woven together, so that the defining idea of the Delta is one of overlap, of echo, from the graves of bluesmen to the famous highways. Many times I've sketched these four mother roads on a bar napkin. Which is to say that the Delta is my home, my family's home, for generations now. I know it well, and I'd never heard about the barn until Patrick told me I needed to take a ride.

The barn where Emmett Till was murdered, he said, was just some guy's barn, full of decorative Christmas angels and duck-hunting gear, sitting there in Sunflower County without a marker or any sort of memorial, hiding in plain sight, haunting the land. The current owner was a dentist. He grew up around the barn. When he bought it, he didn't know its history. Till's murder, such a brutal window into the truth of a place and its people, had been pushed almost completely from the local collective memory, not unlike the floodwaters kept at bay by carefully engineered reservoirs and levee walls.

Patrick Weems runs the Emmett Till Interpretative Center, or ETIC, in Sumner, Mississippi. His job is to make sure people never forget about Emmett Till's murder. We set a time to spend a day following the Till trail that his organization was working to establish and protect; it is his goal to preserve all the places associated with Emmett's murder, with the hope that these places might teach future generations to be better than their ancestors. Weems is skinny, with hair nearly to his shoulders and a dark sense of humor. A local Black political leader said he decided to trust Weems because only progressive white boys wore their hair like that. Patrick climbed into the passenger seat of my truck holding his breakfast: an ice-cold can of Coca-Cola.

Excerpted from The Barn by Wright Thompson. Copyright © 2024 by Wright Thompson. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

To limit the press is to insult a nation; to prohibit reading of certain books is to declare the inhabitants to be ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.