Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

When I was seven years old, my mother purchased a copy of Sports Illustrated for me. She taught me to read before I entered school, and encouraged the practice however she could. And what more encouragement could there be than this issue of Sports Illustrated, which featured my hero, Tony Dorsett, running back for the Dallas Cowboys. This was 1983, an era of American football when running backs seemed as large as champions pulled out of Greek myth. How could a man of Earl Campbell's might move so fast, racing past one defender and then staving in the chest of another? How could Eric Dickerson run so high, against all convention, bounding through holes in the defense, an obvious target that was never caught? These days I will occasionally watch an old clip of Roger Craig, through will alone, breaking off a forty-six-yard run against the Rams or Marcus Allen reversing field in the Super Bowl. But back then, in an unwired world, stories, words, histories—none of it could be gotten on demand. If you bore witness to such a feat—as I did with Allen—it lived in memory until the broadcast gods decided you could see it again. And so a magazine featuring the exploits of one of these heroes was not just, to me, an assembly of words and stories. It was a treasure.

Because I really did believe that Tony Dorsett was magic. He was five foot eight, built ordinary as one of my uncles. But when he slid the lone-starred helmet over his head, he transformed into something untouchable. I remember him darting through the defense, shifting direction at full speed, dancing, sprinting the length of the field, and outrunning an entire team. But whatever my affinity for Dorsett, this is not what I remember about that issue. In fact, until a few months ago, I'd forgotten that Dorsett was even on the cover at all, because deeper in the magazine, I found a story so unsettling, so horrific even, that it blotted out every adjacent detail.

The story was titled "Where Am I? It Has to Be a Bad Dream." Its subject was Darryl Stingley, who'd once been a wide receiver. I thought of wide receivers as mythical too—contortionists like Wes Chandler, extending back to snag a ball bouncing off into the ether, or acrobats like Lynn Swann, dancing in the air. I absorbed these exploits on Sunday mornings through highlights curated by the NFL itself. But a magazine like Sports Illustrated existed beyond the garden, out in the street where journalism and literature collided. And out there was neither magic nor myth—only the realest of monsters.

And so I read the true story of Stingley, who back in 1978 took a hit on a slant route and woke up in a hospital. The story began there, in the hospital—with Stingley unable to move a single limb, unable to call to his mother or wipe the tears running down his face. In an instant, the contortionist had been rendered quadriplegic. Only a few paragraphs in, I wanted to put the magazine down forever, to escape the story, but I was held fast by forces I could not then understand. I knew that there was something different in the storytelling, something in its style, that pulled me toward it with the gravity of a star, until I was there, I was on the field, yelling, pleading with Stingley to watch out for the incoming hit, and then in the hospital, right next to him, helpless to relieve the horror blooming in his eyes as he realized his fate. And then the star became a black hole, and I crossed an event horizon where I was no longer imagining myself there with Stingley, but was Stingley himself, and it was my body pinned to the bed, and the spokes were drilled into my skull, and it was I crying out to a heedless god.

I haunt if you want, the style I possess. And I was haunted—by a style, by language. And, dimly, instinctually, I understood that the only exorcism lay in more words. I went to my father and bombarded him with questions, because that was the kind of child I was, always (to the annoyance of my siblings) asking why. My father's way of dealing with this was patented and that day he executed the maneuver to perfection. He led me to the back room, where he kept a large collection of books, and pulled one down from the shelf. The book was They Call Me Assassin. It was the memoir of Jack Tatum—the defensive back who'd laid the crushing hit on Stingley.

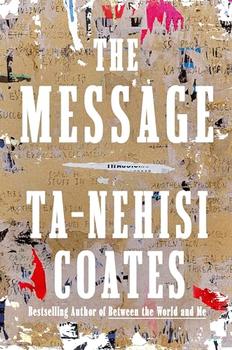

Excerpted from The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Copyright © 2024 by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Excerpted by permission of One World. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.