Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Chapter 45

The night Luce finds Pluto, I am late in getting home, having spent the whole day helping Sulien with the star house. She has been keeping her eyes down now and then, as everyone has, trying to spot the planets lodged in the ground. The trick, of course, is that everyone had forgotten about the planet demoted at the turn of the millennium, so no one was looking for it.

That evening Luce asks if I want to take a walk, and I agree and we set off. I'm not sure where we're going, but I let Luce lead and soon I find us walking along the perimeter of our town. Luce walks with a limp, and I can hear her breathe in with a jerk now and then, holding inside her a very ancient kind of pain. It may have to do with my father, the way that she's no longer a twin.

Just as we've gotten as far as the town will allow—the furthest point from the duplex within the town limits—just as I'm about to tell her I'm freezing and we should head back, she knocks her steeltoe boot three times on the ground and I look and there is Pluto. Pluto, the god of the underworld, here next to the town's graveyard. And also, this confirms it: the contours of our town are precisely overlaid with that of the dimensions of the solar system, give or take some fuzziness at the border. But borders as a rule are fuzzy, and in this case I equate that fuzziness with the vague limits of the Kuiper belt.

I ask her to tell me more about the imitation world my father felt we are a part of. She looks at me with raised eyebrows.

"I don't believe it, but it calms me to hear you say it," I say. "Like a fairy tale."

She sighs and asks me if I have a light.

Luce says that my father believed we were all part of a very great fabricated reality, that we have been placed here strategically, as part of a way of knowing what kind of patterns humans will discover and what kind of patterns humans will invent. Then, as if to illustrate this point, she uses the tip of her steel-toed boot to make a circle in the soil and then she makes shapes inside the circle that look like portions of continents. She tells me that my father believed some other cognition was watching us and our fabricated reality. It would keep watching us until it learned what it needed to know, and then—then it would end things abruptly. Everything would rush toward a single point that he called The Beautiful End. It would be like those old analogue television sets turning off. The way when you flipped the switch, the light and sound would bend until it disappeared into the vortex at the center of the screen. Then she takes her shoe and runs it over the world slowly until the soil is just a big smear.

I can't help thinking that The Beautiful End, the old TV turning off—it sounds precisely like what happens at the center of a black hole.

"He knew he was made of flesh and blood and bone," she says, and I can't help looking out over the graveyard, "a creature bound to the laws of entropy, but he believed he was an organic being caught in an artificial construction. Sort of like an ant farm—the ants themselves are real, but the terrain they navigate is false. We build it just to watch."

She goes on to explain that he thought we all believe we have agency because it is simpler that way, to believe that we are the engineers of our own happiness and sorrow. But my father believed that the laws of the world were the work of some cognition beyond our understanding.

"But doesn't that mean we don't have control over our choices? Doesn't that mean that all of the cruelty of which we are capable is not human-made and human-induced—that it's all unfolding because of some other force?" I ask. "To me, that feels like a cop-out."

"Your father would have pointed out that you're talking about the ants, there," Luce says. "Humans aren't responsible for the way the ants behave, who they harm, who they love, how they build and destroy their own farm. Humans are only responsible for constructing the environment and letting the ants do what they will."

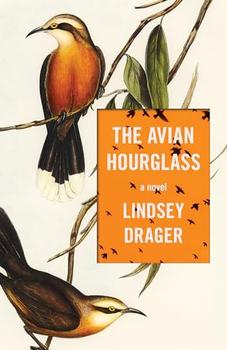

Excerpted from The Avian Hourglass by Lindsey Drager. Copyright © 2024 by Lindsey Drager. Excerpted by permission of Dzanc Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.