Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Memoir

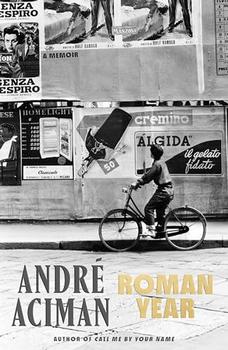

by Andre Aciman

A part of me wished my mother had screamed back at him to let him hear what a deaf woman can produce once she's been pushed to the limit. No one I'd ever met had rivaled my mother's scream.

But had my mother yelled back, he would have abandoned us there and then and never spoken to us again. She knew it, and we knew it, which is why neither my brother nor I attempted to translate what he was shouting.

* * *

The official asked my uncle to accompany him to an office where he'd have to sign release forms. But instead, Uncle Claude handed my mother his Bic ballpoint pen to sign the forms herself. The two of them headed to the office while my brother and I stood watch over the suitcases, which were lined up in a row that ran half the length of a long, begrimed hangar filled with timeworn, decrepit bric-a-brac. Each suitcase now seemed smaller than in the large, formal living room that had once been my great-grandmother's salon when she received guests.

In the stuffed hangar in Naples, I kept staring at our suitcases and, for the briefest moment, thought that some were even happy to see me again while others turned away, determined to ignore me, perhaps because after spending so much time in our old living room, they were upset at being abandoned to handymen who spoke a language that no suitcase could fathom: Neapolitan—a language it would take me years to understand and ultimately to adore. I looked at the suitcases, as though prodding them to acknowledge me, but the swollen leather boxes were determined not to respond.

I remembered when they had first been brought into our family, a gaping litter lying about shamelessly open-mouthed in the large living room. They were made of thick, industrial leather and held tight together by two thick belts that were fitted through two wide leather-strap tabs stitched into the suitcase itself to keep the belts in place. Egyptian customs regulations prohibited locking anything, as customs officials wished to examine the contents of each suitcase. But at customs, no one had required us to open any of our cases, as they were satisfied by the future prospect of receiving one bribe when my father left and another upon Aunt Elsa's departure.

We all felt sorry for Aunt Elsa. Her eyesight was deteriorating, but she did not ask the servants to help her pack; nor was she willing to ask the help of her few remaining Greek and Italian friends in Alexandria. She didn't want anyone nosing around. Je suis indépendante, she used to say whenever questioned about her congenital parsimony and her lifelong status as a widow. She had never wanted to marry anyone except for the shiftless Victor, who had barged into her life, married her, and then died, because, as my grandmother used to say with a wry expression on her face, he preferred to die. My grandmother's husband had also preferred to die before his allotted time. Indeed, everyone who married into the Cohène family found in death the perfect exit to a marriage where what passed for love had consented to spend a couple of token evenings but not a second more.

When Mother asked Aunt Elsa how many suitcases she might need, Elsa replied that five would do. My mother didn't believe her, but complied. She purchased suitcases from a merchant on Place Mohamed Ali, ordering thirty in all. Ten for us, ten for my father, five for my grandmother, and five for Aunt Elsa. Little did we know that within weeks we would more than double the order, and indeed watch the owner of the shop admit that he had no more to sell, but that for the time being, he had a few sharkskin suitcases that were more supple and could easily fit under a bed. My mother had begged him to have more of the larger ones made as the date of our expulsion from Egypt was drawing near. The merchant promised. This, after all, was the selfsame man who had purchased all our furniture, both in the city and at our beach house, paying a pittance for everything we owned. There was no discussion, no haggling, and as soon as he had named his price and my mother accepted it, he reached into his breast pocket and, pulling out a large leather wallet, hastily counted a wad of bills, placing the agreed-upon cash in my mother's hand. Within days, our furniture and almost everything that the government hadn't already seized was whisked away. I didn't watch the removal of our furniture. But when I stepped into our old apartment, I was startled to see bare rooms and no rugs on the floors, just the white trace of missing paintings on our yellowed walls. The dining room furniture was gone, and the kitchen as bare as a newborn. I still expected to see our cook, Abdou, there, but one of the service doors was locked shut, and there were piles of dirt behind where the refrigerator and the oven once stood together, like close cousins who'd been forced to separate. My mother wanted me to see this, she said. Why? I asked. "Comme ça," because. That explanation stayed with me for life. Her two words spoke everything in her heart.

Excerpted from Roman Year by Andre Aciman. Copyright © 2024 by Andre Aciman. Excerpted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

A book is one of the most patient of all man's inventions.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.