Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

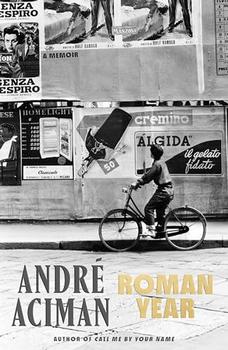

A Memoir

by Andre Aciman1 Please, Don't Hate Me

"And please, don't hate me. I'm no ogre," said my great-uncle Claude as he was about to walk out of our new apartment in Rome and head toward the stairway.

Standing at our door, Uncle Claude, or Claudio as he was known in Italy now, was quoting the very word his sister had used months earlier in Egypt when trying to gloss over ugly family rumors about him. "He has a very good heart, so stop thinking of him as an ogre," she'd say, looking straight at my brother and me and using a word drawn mostly from fairy tales. "Yes, he does have a bad temper, but think of him as impulsive—we're all a bit impulsive in our family, aren't we?" she'd add about the man we were to meet as soon as our ship reached Naples. "Impulsive" was a far more tactful way of describing a man whose bouts of seething rage were forever impressed in the memory of those who knew him. Aunt Elsa must have written to him from Egypt telling him that we were thoroughly terrified of meeting him.

By using her very word, ogre, at our door that day, he had found a sly, mean-spirited way of showing that, thanks to Aunt Elsa's tireless letters, he was fully aware of what was being said about him in our household in Egypt. Aunt Elsa had a big mouth. She couldn't help it, and was the first to admit that she talked too much. "Je suis gaffeuse," I'm a blunderer. She must have told him countless things about us: how my parents always quarreled, how she could hear my brother and me tussling in our bedroom, and of course how we were mean to her and showed no respect for an older woman in her late eighties about to lose her eyesight. How could he not want to show that he was all too well aware of the goings-on in the family?

In his letters to us about Rome, Uncle Claude's description of the three-bedroom apartment he offered to lease us had been candid and accurate enough. Nearby, he wrote, were a small public park, a supermarket, a department store, all manner of groceries, and four movie theaters that, unfortunately, played dubbed films only, but one easily got used to this. We were going to love Rome; he was sure of it. My grandmother, his sister who was older than Aunt Elsa, their other sister, had written to tell him that I was interested in history. He wrote back promising to show me the famous and not-so-famous Roman sites, some unknown to tourists and locals alike. As with so many things, he added, one needed more than one lifetime here, even two weren't enough—nothing like that cloaca of ours, Alexandria.

The little I knew about Rome I'd gleaned from a small map I'd obtained from the Italian consulate in Alexandria. Our neighboring streets in Rome would bear dignified names drawn from Virgil's Aeneid: Via Enea (Aeneas), Via Turno (Turnus), Via Camilla (ditto), while Via Niso (Nisus) led directly into Via Eurialo (Euryalus), as if the city planners knew that, as in Virgil's epic, the love of Nisus for Euryalus could never have borne their separation. I did not expect to run into Camilla or Turnus girding for battle as they buckled their cuirasses, but I knew that the weight of legend and history permeated every facet of Rome. By contrast, in his view, our city was a cloaca. I had to look up the word.

I liked Uncle Claude's impish sense of humor. You could even detect it on his envelopes, which always arrived in Alexandria marked with two capitalized and underlined words beneath our address stating "French Language." He was, in effect, making it easier for the Egyptian censors, who read all mail from abroad, to pass his letter to those responsible for reading the mail in French. It was also his way of announcing to the censor that there would be nothing compromising or incriminating in the letter, since, by declaring its language, he was already showing he was fully aware it would be read. In fact, the censor always opened Claude's letters, read them, and then sealed the side of the envelope where it was opened with a label to inform the recipient it had been scrutinized. I liked his "purloined letter" approach, concealing evidence in plain sight. He had managed to keep the Egyptian authorities in the dark about my father's bank account in Switzerland by writing that he had found Aunt Berta's spirit quite uplifted on seeing her granddaughter safe and sound following her short vacation in Greece. Aunt Berta was none other than my father's banker in Geneva, and the granddaughter a trusted Greek courier in charge of funneling funds abroad. Eventually, the Greek turned out not to be so trustworthy; he gobbled most of the funds in the Swiss account and then decamped with his family to Brooklyn. Uncle Claude, who was an experienced lawyer with contacts in Switzerland, heard of the theft and communicated the fact by telegram to my father in Egypt: grave sickness of our beloved Berta stop granddaughter so broken-hearted not responding stop.

Excerpted from Roman Year by Andre Aciman. Copyright © 2024 by Andre Aciman. Excerpted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Polite conversation is rarely either.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.