Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

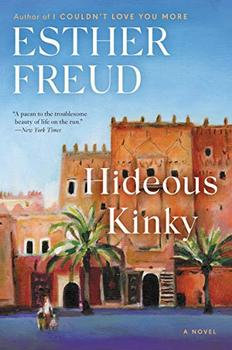

by Esther Freud

Nothing irresistible materialized, and so I applied myself, at first with difficulty, slowly with more ease, until soon there was nothing I wanted to do more than sit at the kitchen table and move on with my story. Memories came back to me, some humorous, others chilling; whole conversations fell word for word from my pen. When I was stuck I'd visit my mother with a list of questions, and as she spoke I'd reimagine what she said from the perspective of my five-year-old self, caught as often by what I hadn't known as by what I remembered. By chance I was living in an area of West London with a large North African community, and there was a Moroccan advice bureau on the corner of my road where sometimes I queued with queries about the correct spelling of a Berber village, the ingredients of a favourite meal. I did wonder, on difficult days as I stared, frustrated, into space, if I should simply return, remind myself of the eighteen months we spent living in Morocco, but I was worried that the memories I'd stored, along with a kaftan, a bead choker and my sister's Arabic schoolbook, would evaporate the moment I arrived. It was only when the novel was finished that I rewarded myself with a trip to Marrakech. As soon as I stepped off the plane and breathed in the scent – dust and heat, diesel, mule – my fears subsided. I was home.

I stayed in a hotel in the Medina, three floors around a courtyard, one toilet on the landing, a tap and a plastic basin to wash clothes on the roof. A hotel so familiar we might have lived in it before. Once settled, I set off for the Djemaa El Fna, the vast square at the heart of the city, reassured to see the women still selling their dark loaves of bread, the men behind their tiers of oranges, the boys hustling and flitting between stalls. Here were the Gnawa shaking their cowrie-beaded caps, drumming as night fell. The next morning I wandered the lanes of the souk, found the wool-dyeing district, the alleyways strung with coloured skeins, the leather district where babouches were hammered into shape. There were the pyramids of spices, the dark green grains of henna, coal sold piecemeal from a hole in the wall.

Later that week I took a bus to Essaouira, dozing as the Koran blasted from the driver's cassette, stopping for lunch at a small, red-and-green-painted town, where tripe stew was served in earthenware bowls, where there was spinach, shredded and oily, flaked with almonds, a dish I'd forgotten that I loved.

By the time I returned I had an excited feeling about my book, and as I packaged up the manuscript and sent it to an agent, I allowed myself to drift off into fantasy: interviews and photographs, who might play the part of 'Mum' when it was made into a film. All the same I wasn't surprised when the pages came thumping back – acting had prepared me for rejection. But it had made me resilient too, and I posted them straight off to the next agent on my list. I'd amassed a small collection of polite, discouraging letters when, early one morning, the phone rang. I'd slipped the manuscript through the door of yet another agent, and it was this agent, telling me she'd been reading through the night, and not to change a word. Unless, perhaps, I had another title?

I had no title at all, had tentatively typed A Home For Us on the first blank page, but a friend had suggested I call it after the game my sister and I played, a phrase we'd used as code for when things became too strange or alarming. 'Hideous Kinky?'

'That's it!' And within a week she'd sold it to an editor (the same editor I still have, thirty years on).

I was exultant, flooded with energy and ideas, as if a fog had lifted, as if the events of my childhood, set down, had made it possible to step into the present. I began work on a new novel, and not long after, as I was sailing down the Portobello Road, I bumped into a friend of my mother's. As a young woman she'd visited us in Marrakech, bringing along her baby, Mob, who we'd strapped on to our backs as the local children did when in charge of their siblings, and run with her out into the square. Mob was grown. She'd changed her name. But her mother congratulated me – she'd heard my news – and asked what I was doing now. 'I've started another book,' I told her.

Excerpted from Hideous Kinky by Esther Freud. Copyright © 1999 by Esther Freud. Excerpted by permission of Ecco. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Wisdom is the reward you get for a lifetime of listening when you'd rather have been talking

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.