Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

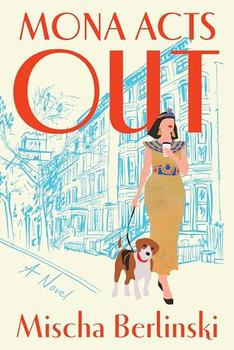

A Novel

by Mischa Berlinski1

On the outlines of Milton Katz's accomplishment, the general shape and structure of his achievement, there was a single point of agreement: not even the most fervent of his enemies denied that the Disorder'd Rabble owed to Milton the remarkable good fortune that was possession of 107 Avenue C.

The story now was company legend: how in 1966 Milton found the abandoned glove factory, little more than a burnt-out husk, victim of the decline in women's formal handwear and a suspicious fire. How squatters were occupying the building: an anarchist commune on the first and second floors, a shooting gallery on three, and on the fourth floor, a Maoist revolutionary organization. How Milton and his guerrilla Shakespeare company seized the fifth floor. How the company rehearsed there during the week and put on free shows every Friday and Saturday night for anyone hip enough to know where to go and brave enough to make their way down to Alphabet City after dark, wriggle through 107 Avenue C's boarded-up ground-floor windows, and mount the unlit staircases. How Milton slept in the space to keep it safe from looters, scaring off thieves with prop swords. How the city shut off power to the building, so those legendary early shows were lit by candlelight, hundreds of theatergoers crammed cheek by jowl to watch a samizdat Hamlet, Tempest, or Merchant. How the fire marshal closed the building in 1970, the front entrance sealed in cement and a security guard stationed out front. How Milton lobbied, solicited, fundraised, cajoled, and pleaded, how he and he alone made the company a New York cause célèbre. How an editorial in the Times called on the City of New York to find a permanent home for this "intriguing, avant-garde, thoroughly modern theatrical company, who deserve a place in our city commensurate with the place they have earned in our hearts." How Alphabet City was by then more dangerous, more degraded, and less attractive to investors than it had ever been, how the owners were desperate to sell. How Milton assembled a consortium of company supporters who bought the building and sold it to the company for one dollar. How after three years in the wilderness, the company returned to 107 Avenue C, and Milton had a large brass plaque installed in the lobby, and how on it Milton listed the names of the donors who made the acquisition of the building possible. How above the plaque, he engraved the lines from which his company would take its name: "Your disorder'd rabble / Makes servants of their betters."

But half a century after the Disorder'd Rabble's founding, real estate was just about the only terra firma in the nonstop, still-ongoing in-house debate on the subject of Milton Katz. They fought about Milton in the rehearsal rooms, the admin offices, in the dressing rooms, at fundraisers and at after-parties. That Milton wasn't dead made the whole debate that much more intense. The idea of Milton just sitting at home in exile . . . his hair unkempt . . . maybe even drooling—the thought of Milton neglected in his old age would rile up those who still loved him. "We should do something for Milton," they would say, as if discussing the renovation of the crumbling statue of some long-forgotten Civil War hero. "It isn't right about Milton. After everything he's done." The very same thought—of Milton lingering, judging, lounging around in his bathrobe—would produce a wave of equal but opposing outrage among the Miltophobes, who favored tearing down the damn statue in its entirety. Between the extremities of love and hate there was no common ground, no place for nuance. Just mention his name and all the old wounds would reopen, and the two camps, like baboons startled by thunder, would squawk and abandon peaceful grooming to bare their fangs and fist each other vigorously upside the head.

If only Milton would just have the common, human decency to die! Then everyone could settle down. The people who, despite everything, still loved Milton could go back to remembering him fondly; the people who, despite everything, resented him could let it all go; and everybody, wherever they stood on the subject of Milton, could trade their best Milton Katz stories over post-show saketinis at the Get Bento Box.

Excerpted from Mona Acts Out: A Novel by Mischa Berlinski. Copyright © 2025 by Mischa Berlinski. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.