Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

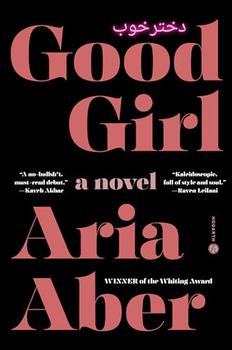

by Aria AberOne

The train back to Berlin took seven hours, and the towel in my suitcase was still wet from my last swim in the lake, dampening the pages of my favorite books. I took the S-Bahn and then the U-Bahn home to Lipschitzallee and walked past the discount supermarket, the old pharmacy, and the Qurbani Bakery with the orange shop cat lounging outside its door. In our building's elevator, an intimate odor assaulted my nostrils: urine mixed with ash. Hello, spider, I said, looking at the cobweb in the corner. The ceiling lamp twitched, turning alien the swastika graffiti. My key, fastened by a pink ribbon, turned in the old lock. Nobody was home. I kicked off my shoes. The cat meowed for food, its dander floating in the air. My room was merely all it had been for so many years: a suffocating box with a tiny window, pink sheets, and that Goethe quote I'd painted in golden letters above my desk. The popcorn ceiling seemed lower than before. I wiped the kitchen counters, walked into my parents' bedroom, opened their closet, and pulled out my mother's cashmere frock. Maybe I cried, maybe I didn't. What I did was lie in bed and sleep until dark, covering my face with her dress.

It's been over a decade now, but the colors of that summer day are as precise as yesterday: I was eighteen when I returned from boarding school, and my sense of melancholy was even more overwhelming than I anticipated. My cousins called me pretentious. The Arab boys who loitered outside the shisha bar sneered at me. You changed, they said, meaning my relative lack of vernacular and my newfound obsession with eyeliner. Back then, I still wanted to be a photographer, a small Olympus point-and-shoot knocking around in my backpack. In my first days back, Berlin bloomed at the seams with rotten garbage. Ants crawled out of the sockets in my father's living room, a small street of them always leading up the wall and out the window; no matter how much poison we sprayed into the electrical outlets or taped them shut—-they just returned. And though prophesied to soon be extinct, the bees were also everywhere. They covered the overflowing trash cans in the city, or you'd see them lazily dozing on outdoor café tables, where they fattened themselves on crumbs of sugar or lay unconscious next to jars of cherry jam. I brushed the dirt out of my hair and rinsed it from my face and all I could hear, even in the early morning, was the howling of sirens over the frenzied songs of birds, which chirped and chirped and chirped.

In August, I enrolled at Humboldt Universität for philosophy and art history, not because I wanted to study but because I wanted the free U-Bahn pass. And so I let the glittery, destructive underworld of Berlin sink its fangs into me, my solitude alleviated only when I went out at night and got lost in some apartment with tattooed men and women who did poppers underneath a framed picture of Ulrike Meinhof. Then I went home, my nose bleeding, my hair smelling of cigarette smoke, and was confronted by that disappointed look on my father's face, my grandmother's suspended in a perpetual frown. I had been lifted out of the low-income district of hopelessness and sent to one of the best schools in the country, and yet here I was, my mother was dead, soon the city would be covered in snow again, and I was ravaged by the hunger to ruin my life.

Autumn was short and humid, and then, overnight, it was winter. On the news, I saw middle-aged men with pearlescent smiles and young blond TV anchors in starched suits reporting about the financial crisis, the lack of jobs, the jammed Eurotunnel, snow collecting on the spires of basilicas in Northern Italy, and somewhere, everywhere, a missing girl, or an Arab man detained for terrorism, or a building with asylum seekers set on fire. In Berlin, the cathedrals' stained glass was covered with frost, and most days, I put on my red hat and my black coat and walked out into the crunchy snow to my job at the jazz café in Kreuzberg, the kind of place with red-painted walls and old leather seats, which tried to present a facsimile of a gone century. I served old German couples, and sometimes they were so close to me I could smell their shampoo, the salt on their skin, and despite myself, the hairs on the back of my neck stood up in desire. To pass the time, I imagined the men touching me while their wives watched. Instead, they ignored me or, when I bowed down to serve their burgers, asked which God I believed in. How old I was. Where I was from. And occasionally one of them would trace my earring or touch my butt when I passed, and my body surged with repulsion.

Excerpted from Good Girl by Aria Aber. Copyright © 2025 by Aria Aber. Excerpted by permission of Hogarth Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.