Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

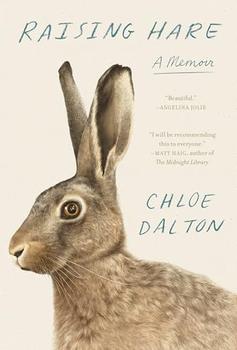

A Memoir

by Chloe Dalton

I considered the options. I could leave the leveret where it was, hoping that it would find its way back into cover and be retrieved by its mother before it could be found by a predator or crushed by the wheels of a passing car. I could pick it up and tuck it into the long grass with the risk – I thought – that its mother might not be able to find it, since it could have been carried or chased some distance from its original hiding place, or that she might reject it.

As a child, I had loved lambing season and used to spend time on a nearby farm assisting with the lambing. I had seen the way a mother sheep, or ewe, could pick out her young from a field of lambs by its smell alone. Any other lamb that approached her, or tried to drink her milk, would be firmly pushed away. I remembered watching a farmer persuade a ewe whose own lamb had died, to suckle an orphan from another mother by wrapping it in the skinned pelt of her dead lamb. Only if the orphan smelt sufficiently like the lamb she had lost would the foster mother raise it. Transferring my alien scent onto the leveret by picking it up – even if just to move it by a few feet – might be to kill it with kindness.

It seemed impossible that the small animal at my feet could survive by itself in a landscape teeming with dangers, including foxes and the hawks I often saw, hovering close to the ground before closing their wings and dropping like stones upon their prey. Lying in the open, the leveret had no protection against these earth or sky–borne killers. However, I knew that human interference could do more harm than good, so I decided that I had better let nature take its course. I would leave it where I found it, in the hope that it would hurry into the long grass as soon as I had gone and be reunited with its mother. I counted the number of fence posts so I could remember the spot and went on my way.

When I returned, four hours later, I had almost forgotten the leveret. But there it was, on the open track, exactly as I had left it. The fact – as I later learned – that young leverets do not leave their hiding places during daylight hours made its location all the more striking. It lay without a clump of grass or scrap of cover to conceal it, with buzzards wheeling in the sky above, keening mournfully like lost souls. I hesitated, considering the several hours of daylight that still remained. It seemed odd that the mother hare had not come back to reclaim her young, as I thought she surely would have done. I weighed the possibility that the leveret had been injured by the dog, or that its mother had been killed. In either case, if it did not move from the track, the chances that it would be hit by a passing car or attacked and eaten increased the longer it lay in the open.

Acting on instinct, and still uncertain about the right course of action, I decided that I would take the leveret home until nightfall, when I would return it to where I had found it. To avoid touching it with my hands, I gathered several handfuls of the dead grass fringing the track. I crouched down on the ground, half expecting it to dart away. It did not flinch. I placed one hand on either side of the leveret's body, and lifted it carefully to my chest, wrapped in the grass, before walking the last few hundred metres to my back door.

Once home, I placed the leveret anxiously on a countertop so I could examine it for injuries, wrapped loosely in a new yellow dust cloth. To my relief, I could find no sign of bleeding or a wound. It pushed itself up on trembling front paws, each barely half the length of my little finger and as slender as a pencil, and sat unsteadily on its hindquarters, blinking, its nostrils flaring as if it were taking in its strange surroundings. The leveret looked even smaller in the house than it had in the field, dwarfed by any object designed for human purposes. But it seemed unafraid and made no attempt to run away from me. Its mouth was a tiny sooty line, situated on the underside of its rounded little head and curved down at each corner as if it were already slightly disappointed by life. Its ebony eyes had the faintly milky, purple sheen of many new–born creatures. Its whiskers were short and stiff, while its hind legs bent at a sharp angle, its rear paws were almost half as long as its body.

Excerpted from Raising Hare by Trent Dalton. Copyright © 2025 by Trent Dalton. Excerpted by permission of Pantheon Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.