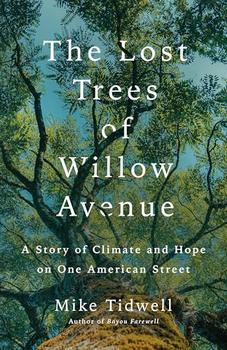

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Story of Climate and Hope on One American Street

by Mike TidwellIntroduction

The biggest trees on my street weren't yet sick and dying when I moved to the 7100 block of Willow Avenue in Takoma Park, Maryland. There were true giants back then, red and white oaks, tall and broad, offering a daydream greenery of good health. I was in good health, too. I was twenty-nine years old. I ran three miles per day. I grew native wildflowers in my backyard garden a few hundred feet from the border with Washington, DC.

But that was 1991, before the chaos of climate change really settled in over this narrow block of fourteen houses—and settled in over the world.

Thirty years ago, scientists and journalists had to travel to the Arctic or Australia's Great Barrier Reef to see the beginning impacts of global warming up close. Three decades later—after the dumping of nine hundred more gigatons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere from oil, coal, and gas combustion—those impacts are everywhere. My neighborhood block, a microdot on any Google map, has shifted to a whole new universe. Maybe you see it where you live, too.

Those old oaks, casting muffled pools of overlapping shade, formed a durable ceiling of branches here in the 1990s and into the 2000s. Then came the years of heat, the weird rain, the beetles, and finally, starting in 2019, a sudden calamity. Today, tens of thousands of mature trees across Takoma Park and adjoining cities and counties survive only as mute tombstones, the chainsawed stumps of a region-wide graveyard of lost giants.

There were no deer thirty years ago on my block; now they roam everywhere, spreading Lyme disease from ticks that survive our milder winters. Neighbors show photos of those "old" winters, decades back, with bundled-up children atop sleds in the deep snow of lower Willow Avenue's steep hill. And past summers? Old newspapers show fewer overheated people and faces, it seems, at the Fourth of July parade. Now umbrellas are a common parade feature as the natural parasols of trees decline. My church, meanwhile, a block from my house, never experienced urgent water problems until the altered weather patterns of the last few years. Now there's an elevated flood berm on one side of the church—price tag $45,000—to keep water out of the basement preschool.

Every day, I think about this: If life is so different here, so scrambled in this old trolley suburb bordering America's capital city, where can anyone hide on this planet? At one point in my long personal battle with Lyme disease, picked up from a tick in my backyard, I couldn't read or write or understand someone speaking directly to me. But I have access to medicine and professional treatment. I can't imagine the lot of Senegalese villagers penniless and suffering through the latest round of climate-induced dengue fever. Or the paycheck-to-paycheck Louisiana shrimper, buffeted by bigger hurricanes and ruined by drowning wetlands.

There are still big trees on my block today—elder oaks, shrinking in number, nobly hanging on despite it all. But if they could, if those trees had legs, they would run away from this place, I think. They would head north, maybe three hundred miles, to western New York or southern Canada, to a latitude where at least the temperature is closer to what they were born into as acorns generations ago in my Maryland town. But that's just temperature. They'd still be prone to the more frequent storms and higher winds and altered insect patterns that are stressing out trees and killing them the world over. Even with legs, the old oaks on my block could not run away.

I did not become a climate activist years ago to save trees. I did it, first and foremost, to save the future of my son, Sasha, now twenty-seven. But the oaks on my street are a fair measurement of our collective progress on global warming. Wherever mature oak trees are found, in urban forests or wilderness settings, they are a keystone species, indicating ecological health. Beyond the bounty of acorns, they are evolved to support and nourish more insects—and thus more birds and reptiles and mammals that feed on them—than any other tree genus in North America. The loss of even one big oak can radically disrupt the ecosystem of an entire local street. On my block, we've lost four giant oaks just since 2019—and others will pass away soon.

Excerpted from The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue by Mike Tidwell. Copyright © 2025 by Mike Tidwell. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Give me the luxuries of life and I will willingly do without the necessities.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.